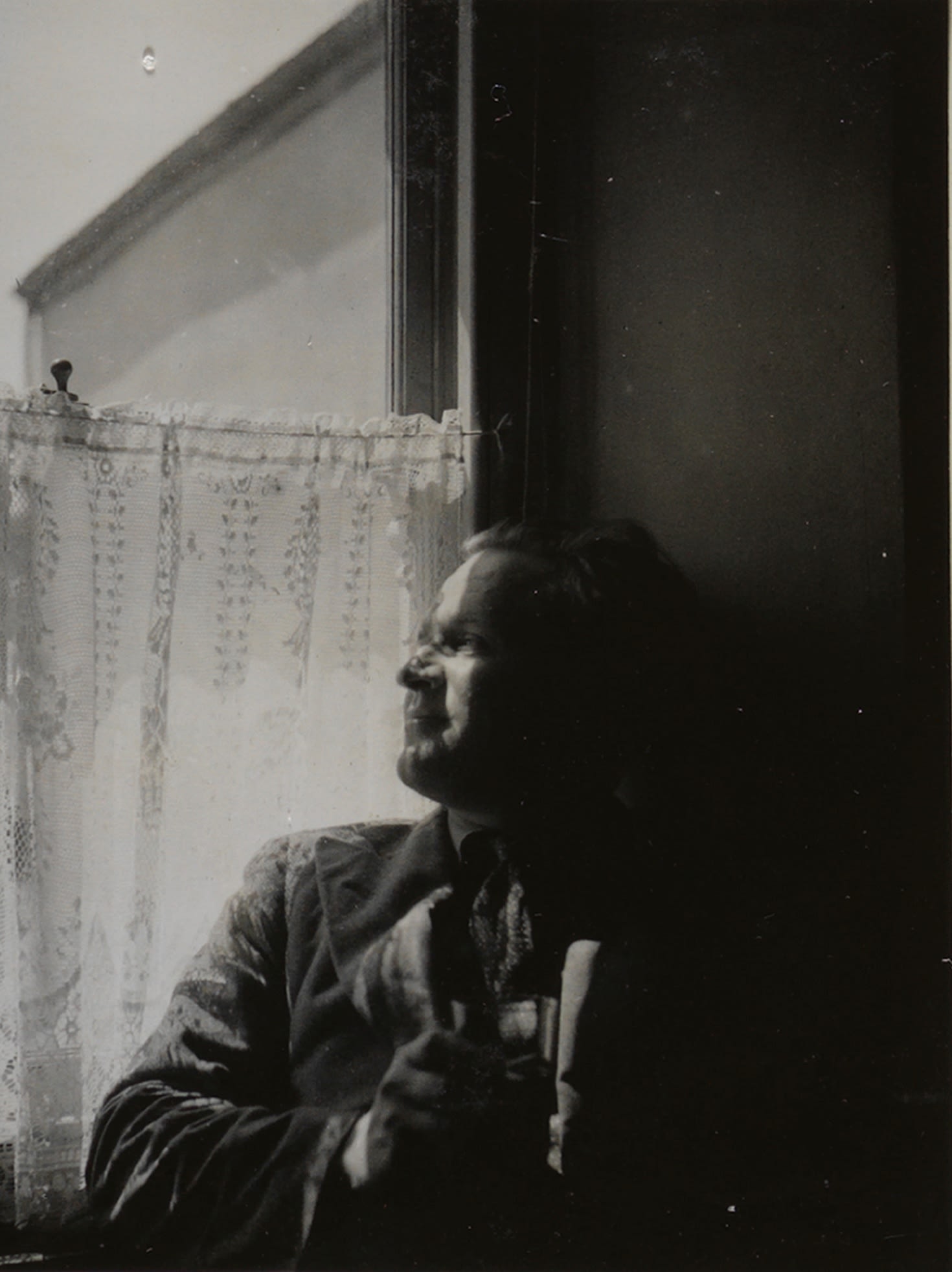

Stephen Tomlin: A Biographical Sketch

By Michael Bloch

Stephen Tomlin had a touch of brilliance. He possessed a sharp intellect; he showed prowess as an actor, poet and musician; he was considered a fascinating conversationalist. Strikingly handsome in his twenties, and bisexual by nature, he was also (to quote his Times obituary) ‘one of those figures of terrific charm with whom most people fall in love’. These qualities endeared him to the Bloomsbury Group: for a while he was one of their most cherished adherents. Yet his life was unfulfilled: psychological problems prevented him from making the most of his talents, and drove him to drink, drugs, and a sad and lonely death at the age of thirty-five. His main legacy consists of his output as an artist, sparse in quantity but of considerable beauty and originality. In his twenties he worked as a sculptor; in his thirties, as a designer of ceramics.

‘Tommy’ (as he was known to his intimates) was born in London on 2 March 1901, son of a Chancery barrister who became a senior judge and was raised to the peerage. He followed his father and older brothers to Harrow, where he was a popular boy (who excited the passions of not a few contemporaries) and won all the prizes, also achieving renown as an actor, singer and poet. But by the time he left the school at the end of 1918 he was in the throes of depression, no doubt partly due to the Great War: term after term, he witnessed boys he had known or loved leave for the front and either not return or do so mutilated in body or mind.

In January 1919, just seventeen, Tommy was admitted to New College, Oxford to read history: but he continued to feel restless and left the university after only two terms. During his brief Oxford residence he became obsessed by the Shelley Memorial, an enormous homoerotic nude statue of the drowned poet by the Victorian sculptor Henry Onslow Ford. A sonnet he dedicated to Roy Harrod, a fellow undergraduate (later a famous economist) who was infatuated with him, suggests that he was already leading a varied and promiscuous sex life. It is not clear how he spent the year following his departure from Oxford, but he saw much of two mentors who would both later become successful novelists – the Old Etonian millionaire Leo Myers, and Sylvia Townsend Warner (whom he had known since Harrow where she was the daughter of the history master).

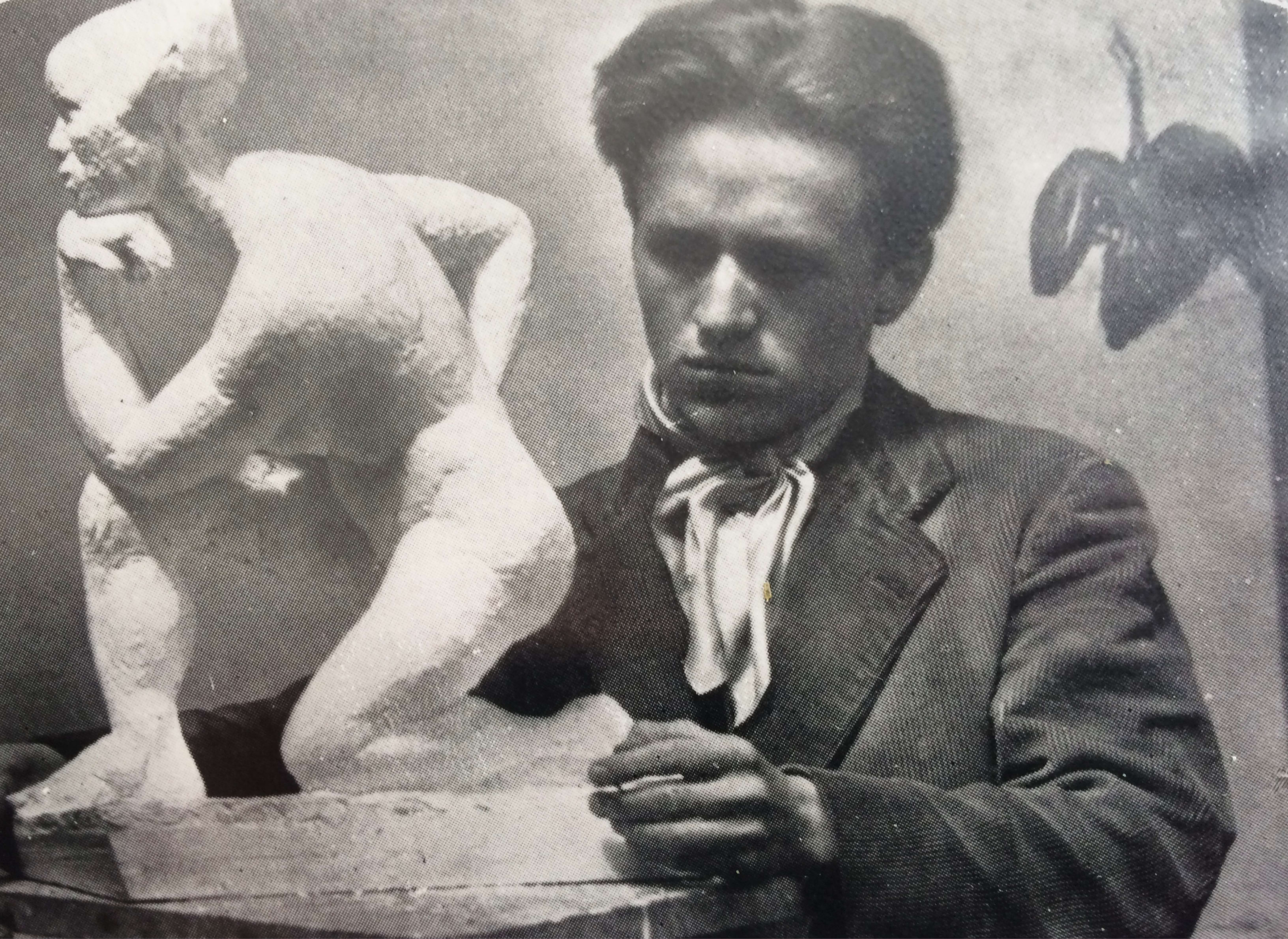

By the autumn of 1920 Tommy, possibly inspired by the Shelley Memorial, had decided to become a sculptor, and was apprenticed to Frank Dobson, a talented artist (and friend of Myers) whose work represented a transitional phase between traditional sculpture and modernism. They became friends and visited Paris together, where they found inspiration in museums and galleries and were introduced to opium and cocaine. (Dobson managed to kick the habit; Tommy did not.) After a year’s training with Dobson, Tommy retreated for a further year to a remote village in Dorset, Chaldon Herring, where he formed a close platonic friendship with T. F. Powys, a reclusive novelist in his forties who had not yet attempted to publish his fiction. With the aid of Sylvia and others Tommy managed to bring Powys’s work to the attention of publishers: it soon saw the light of print and, thanks to Tommy, the formerly obscure Powys became a well-known man of letters.

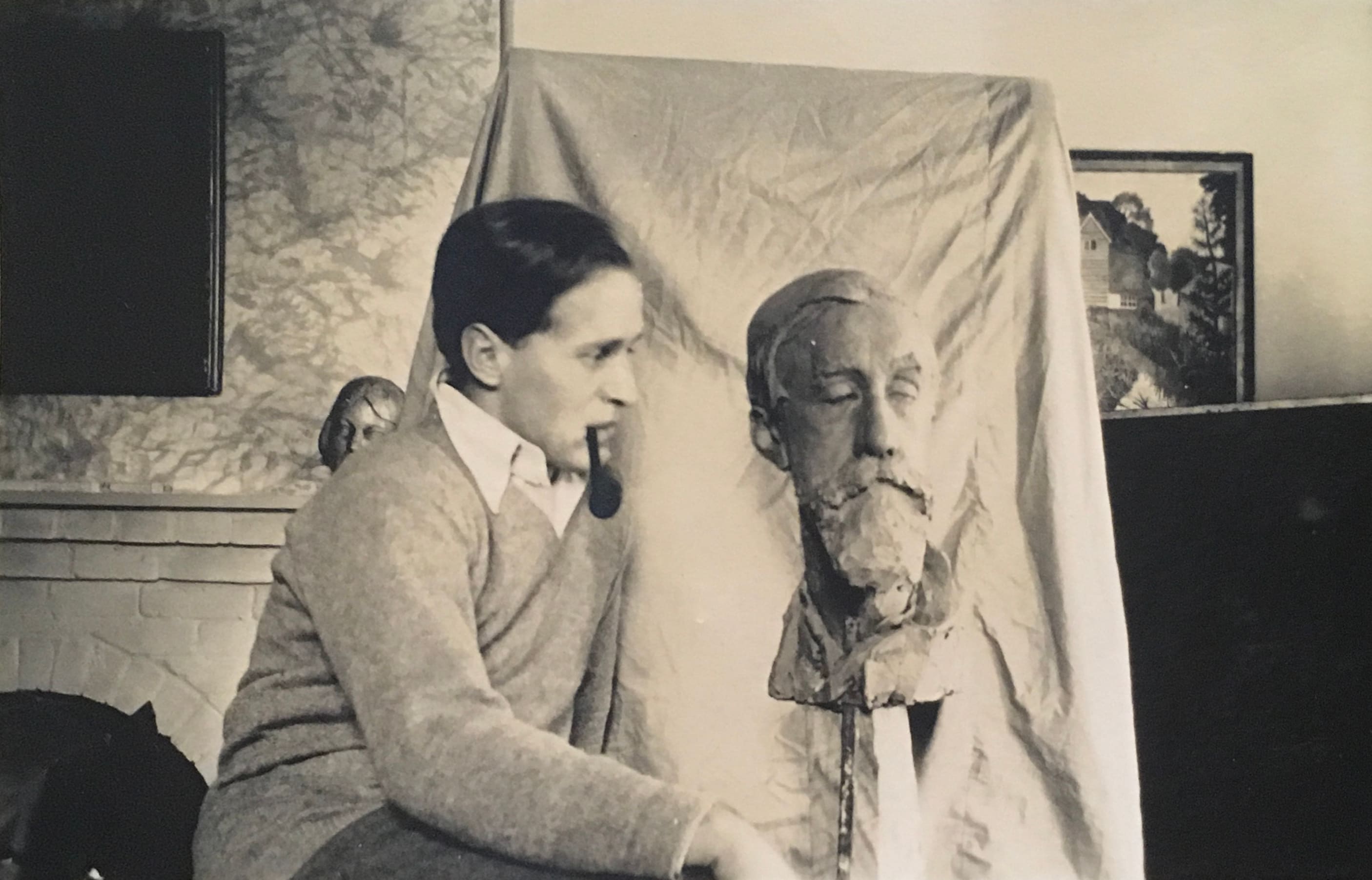

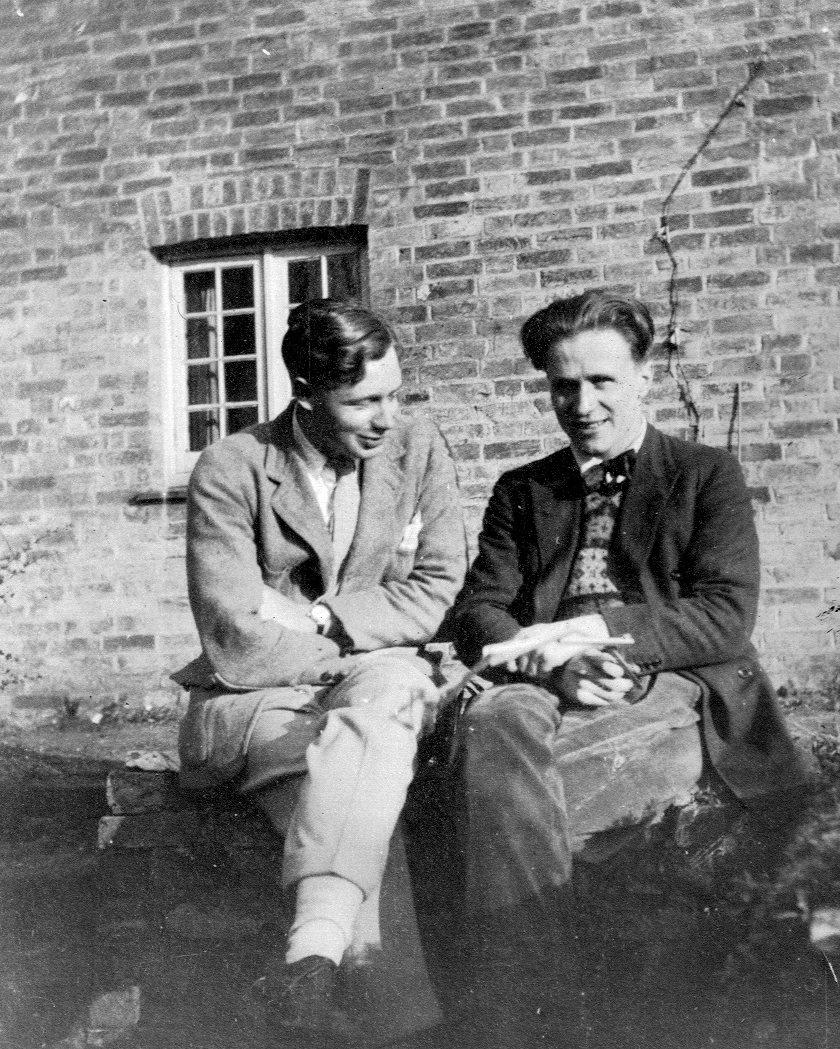

Meanwhile, on a visit to London in the summer of 1922, Tommy had met David ‘Bunny’ Garnett, a charismatic bisexual novelist eight years his senior who was closely involved with the Bloomsbury Group, having had an intense wartime friendship with Duncan Grant. Tommy and Bunny formed an instant attachment, which was certainly sexual for a time. Bunny visited Tommy at Chaldon; and when Tommy returned to London early in 1923, installing himself in a studio in Fulham, the first sculpture on which he worked (indeed, the first of his works known to have survived) was a portrait head of Bunny carved in Ham Hill stone. Tommy had already met Duncan Grant and Maynard Keynes; at Bunny’s thirtieth birthday party in March 1923 he was introduced to other leading members of the Group – Lytton Strachey and Dora Carrington, Leonard and Virginia Woolf, Clive and Vanessa Bell.

Tommy was drawn to the ‘Bloomsberries’ by their love of intellectual discussion, their bohemian lifestyles, and their rejection of conventional values and of sentimentality in art. He in turn appealed to them with his charm, intellect and good looks. But before his friendship with them could blossom he was sidetracked by an all-consuming love affair with another person met at Bunny’s party, the American heiress Henrietta Bingham: daughter of a newspaper tycoon who would later become United States Ambassador to London, she was undergoing psychoanalysis with Freud’s English disciple Ernest Jones. Tommy spent several months in her constant company, and executed a bust of her: gazing downwards and slightly tilted to one side, it captures an elusive, coquettish, quizzical quality. As he wrote to her, this was the first time he had fallen seriously in love with another – in all his previous affairs the passion had mainly been in the other direction. He felt wretched when she sailed for America without him in August 1923 – and still more so when she returned to England the following spring but showed no interest in resuming their relationship. He suffered another breakdown, from which he sought relief through psychoanalysis and immersion in his work: to this period belongs his widely admired bust of his sometime lover Duncan Grant.

The years 1925-7 saw the apogee of Tommy’s association with ‘Bloomsbury’. He became a favourite guest at three of their country houses – Hilton Hall near Cambridge, where Bunny moved after achieving success as a novelist; Charleston in Sussex, where Duncan lived with Vanessa Bell; and above all Ham Spray in the Wiltshire Downs, where the writer Lytton Strachey lived in a triangular relationship with the artist Dora Carrington and her husband Ralph Partridge. By the spring of 1926 both Lytton and Carrington had fallen in love with Tommy, who reciprocated their feelings; Carrington painted a portrait of him, while Tommy executed a statue for the Ham Spray grounds. Other friends from this period included the Russian mosaicist Boris Anrep, who used Tommy as the model for his tableau ART in the vestibule of the National Gallery (still there today); and Eddy Sackville-West, a talented but neurotic youth who was heir to the Sackville peerage and often had Tommy to stay at Knole, his family’s seat in Kent. Tommy sculpted a bust of Eddy, described by Lytton as ‘full of finesse and charm’; while Eddy commissioned the surrealist artist John Banting to paint a striking bare-chested portrait of Tommy.

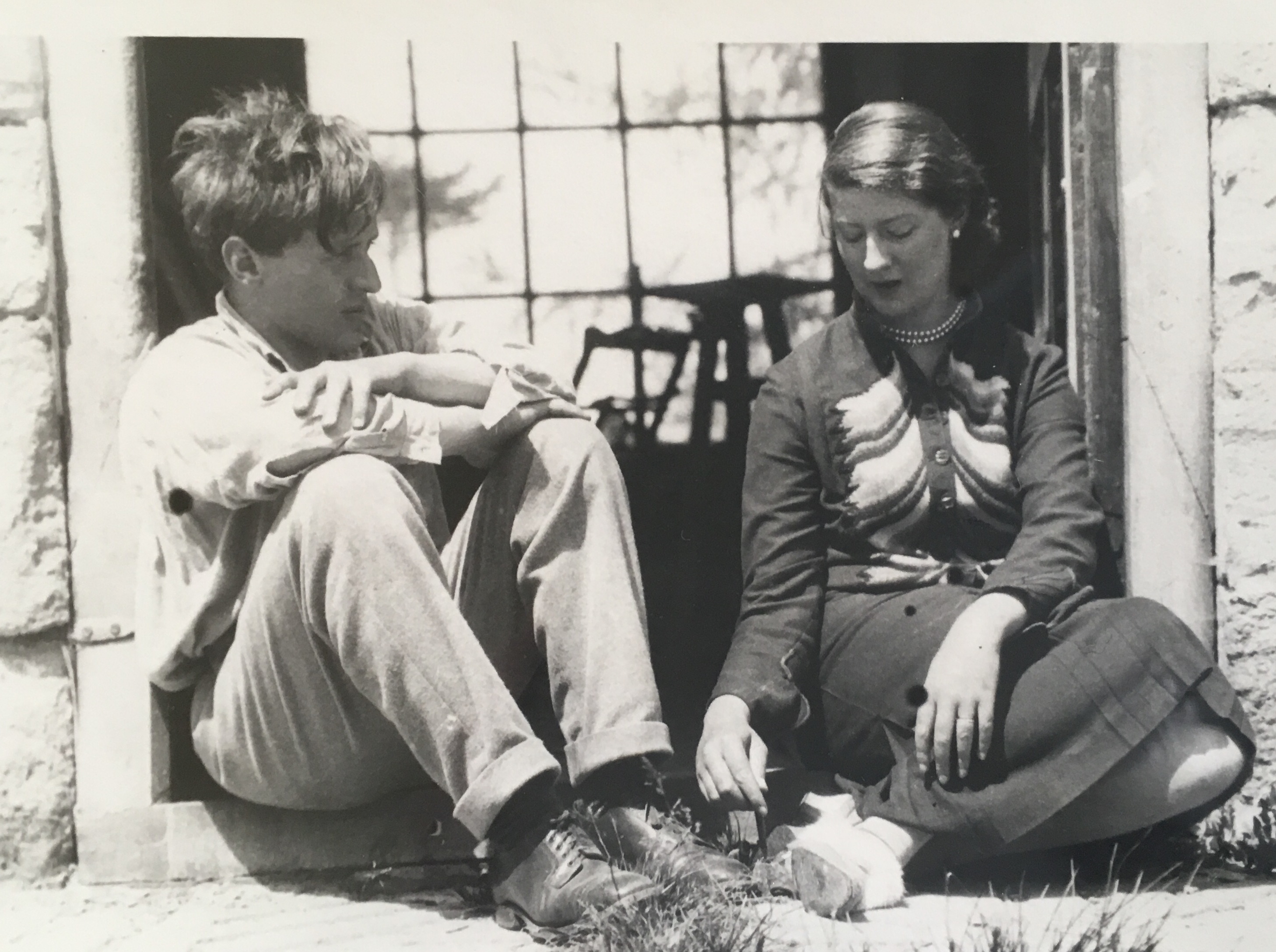

There was some discussion as to whether Tommy might move permanently to Ham Spray, replacing Ralph as the resident bisexual man. Instead, a relationship developed (encouraged by Carrington) between Tommy and Lytton’s niece Julia Strachey, an attractive woman of Tommy’s own age who shared something of his troubled psychology. It was a curious relationship in that Tommy continued to be rampantly promiscuous, while she did not enjoy sex. Nevertheless, her company brought him tranquillity, and during the first months of 1927 they lived happily together in Paris where Tommy studied art. They were both under pressure from their respectable families (on whom they depended financially) to marry, which they did in London in July 1927.

They began married life in a cottage at Swallowcliffe in Wiltshire, a picturesque village within reach of Ham Spray, where they lived from 1927 to 1930. Carrington and other friends who visited them there had the impression that they were leading an idyllic existence. Certainly Tommy did some of his best work at this period, including busts of Julia (1928) and Lytton (1929), which splendidly capture their subjects’ personalities (her insouciance and his amused cynicism). But all was not well. From time to time Tommy would suffer severe depressions, during which he was unable to work and gave vent to violent rages. He was on the way to becoming a hopeless alcoholic and drug addict. And his erotomania was getting out of hand: in her memoirs Julia gives an extraordinary description of parties at which he set out to seduce all the guests.

In 1930 they moved to London, living in a series of furnished flats, Tommy renting a studio for his work in Percy Street, Fitzrovia; but it was not a happy time. His alcoholic and sexual debauches continued; he found it hard to secure commissions owing to the economic crisis; and he became abusive towards his wife. Increasingly they lived apart, Julia visiting her aunt and uncle Dorothy and Simon Bussy (both artists) in the South of France, Tommy going off on walking tours with various friends. Still, when he chose to exercise it he retained all his charm, and several new acquaintances fell under his spell. In the spring of 1931 he picked up a pretty young working-class unemployed hotel porter at a cinema – Humble Williams, known as ‘H.’ – whom he took to live with him as servant and lover: H. would remain Tommy’s devoted companion for the rest of his life and was liked and accepted by most of his circle, including Julia.

In August 1931 Tommy achieved a longstanding ambition when he persuaded Virginia Woolf to sit for a bust. It was not an altogether satisfactory experience: Virginia had originally admired Tommy but had become exasperated by his troubled nature, and was herself feeling depressed. She disliked ‘sitting’ and after a few sessions refused to sit further, so the bust is essentially unfinished. Yet it is generally recognised as Tommy’s masterpiece. As Virginia’s nephew and biographer Quentin Bell (who as a boy adored Tommy’s visits to Charleston) later wrote:

It is not flattering. It makes her look older and fiercer than she was. But it has a force, a life, a truth… Virginia gave him no time to spoil his brilliant first conception. Irritated, despondent, reckless, he pushed his clay into position and was forced to give, while there was still time, the essential structure to her face. Her blank eyes stare as in blind affronted dismay, but it is far more like than any of the photographs.

Whatever the bust’s merits, Tommy seems to have been discouraged by this experience, for he did little sculpture thereafter (though he worked intermittently for several more years on Pomona, a gigantic female statue for the garden of his friend Bryan Guinness at Biddesden in Hampshire, the maquette of which is included in the exhibition). Henceforth his main artistic endeavours were in the field of decorative ceramics. This arose through his friendship with the potter Phyllis Keyes, who had set up her kiln in Warren Street, round the corner from Percy Street where he had his studio. Drawing on classical sculpture and Mediterranean pottery, Tommy designed pieces which were then cast by Phyllis and decorated by Duncan or Vanessa. The two exquisite ceramic figures included in the exhibition, male and female, represent the (now rare) fruits of this collaboration.

Within a few weeks in late 1931 and early 1932 Tommy received a series of devastating blows. In December his elder brother Garrow, to whom he was devoted, was killed in a flying accident. The following month Lytton, whom Tommy regarded as a father figure, died of stomach cancer at Ham Spray, aged fifty-one. It was feared that Carrington, who had often declared that she could not live without Lytton, would now take her own life. In the hope of averting this, Tommy stayed with her at Ham Spray, and seemed to calm her. But on 14 March 1932, while alone in the house, she shot herself. These events plunged Tommy into the blackest depression. In 1933 he gave artistic expression to his mood by writing a remarkable long poem, The Sluggard’s Quadrille, published anonymously in the New Statesman: the literary editor, Bunny Garnett, wrote in his memoirs that he considered it ‘one of the most tragic poems of despair in the English language’.

Tommy’s last years were particularly sad. He drowned himself in alcohol, was incapable of much work, and did not even wish to see much of old friends. His handsome looks went and he became overweight and haggard. In 1934 Julia, having suffered much physical and mental abuse, finally left him. H. remained a faithful companion, but even he often found Tommy’s ways intolerable. One friend Tommy continued to see was the artist Augustus John, another alcoholic, who invited Tommy to spend Christmas 1936 at Fryern Court, his house in the New Forest. While staying there, Tommy had a tooth extracted; subsequently he fell ill, possibly as a result of a fragment of infected tooth falling into a lung, and went into a nursing home at Boscombe near Bournemouth, where he died on 5 January 1937. The general verdict on his death was that ‘heavy drinking had weakened his resistance’. The final contents of his studio included the original busts of Henrietta, Julia and Lytton, probably the people who had meant most to him (though he had turned Julia away when she attempted to visit him on his deathbed).

The tragedy of his unfulfilled life and untimely end should not blind us to his achievement as an artist, or to the fact that, for most of his adulthood, he made an indelible and generally inspiring impression on all he met.