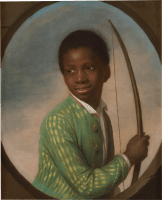

This previously unpublished portrait of a young boy holding a bow has recently emerged from a private French collection and is a notable addition to a relatively small group of portraits depicting Black sitters from this period.

A distinguishing quality of the present work is its strong sense of the individual, suggesting that this is a portrait of a living person and not a more generalised character study imagined by the artist. This is significant, as, for the most part, Black sitters at this date were not considered of sufficient interest to paint formally, and when they were included in portraits, they were generally shown as exotic accessories in larger compositions. It would be a mistake, however, to overlook the context in which this work was produced. Although it shows remarkable liveliness and attention to character, the young sitter shown here was almost certainly an enslaved member of a wealthy household.

By the 1780s, when the present work was...

This previously unpublished portrait of a young boy holding a bow has recently emerged from a private French collection and is a notable addition to a relatively small group of portraits depicting Black sitters from this period.

A distinguishing quality of the present work is its strong sense of the individual, suggesting that this is a portrait of a living person and not a more generalised character study imagined by the artist. This is significant, as, for the most part, Black sitters at this date were not considered of sufficient interest to paint formally, and when they were included in portraits, they were generally shown as exotic accessories in larger compositions. It would be a mistake, however, to overlook the context in which this work was produced. Although it shows remarkable liveliness and attention to character, the young sitter shown here was almost certainly an enslaved member of a wealthy household.

By the 1780s, when the present work was most likely painted, the abolition of slavery was all but a distant hope for Britain’s enslaved population. Although there was quiet support in intellectual circles, the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act was not passed until much later in 1807, and although this was a significant step, it did not end slavery itself. The founding of the Anti-Slavery Society in 1823 was a key step towards complete abolition, and a decade later, in 1833, the Slavery Abolition Act was passed, effectively ending slavery in most of the British empire. Complete emancipation from the ‘apprenticeship’ system followed in 1838, which led to the freedom of all enslaved people in the British Empire.

It is estimated that around 20,000 Black people lived in England in the late 18th century, and many worked as domestic servants in households. The young man depicted here was likely one of these individuals, though his refined attire – most likely invented – may intended to indicate that he held a certain level of respect.[1] He is portrayed in an elegant striped silk coat, which is left casually unbuttoned, showing a white muslin shirt beneath. The coat is enlivened with a line of pink around the collar and wrists, which have a simple design. Gold is a colour associated with wealth and success, and the sitter’s shimmering striped jacket is a statement of his owner’s riches and fine taste.

Although depictions of children as archers were not uncommon at this date, the sitter’s heritage requires a different interpretation of this otherwise familiar reference to adolescence and masculinity. This portrait fits into a pictorial tradition of painted imagery showing Black subjects as archers, which became popular in the mid-17th century. This was the result of a broader fascination with exoticism and the concept of the ‘noble savage’ – a romanticised idea that non-European peoples were uncorrupted by modern civilisation and lived a more rural, pure life. Some of the subjects in these depictions of archers were evidently slaves, as in Young Archer with Parrot (c.1650-70) [Fig. 1], Black Youth Holding a Bow (c. 1697) [Fig. 2], Portrait of a Young African Man Holding a Bow (early 18th century) [Fig. 3] and An Archer in a Turbanned Headdress (1730-40) [fig. 4]. Other images reflect, albeit from a white European viewpoint, the spirit of nature and freedom as in A Young Archer (c.1630-40) by Govaert Flinck [Fig. 5]. There is also Johannes de Visscher’s engraving of Cornelis de Visscher’s Portrait of a Moor with a Bow and Arrow (c.1650), copied from the engraving in reverse direction by George Pulley in the 1750s. Flinck’s archer is a tronie—a portrayal of a characterful figure, often dressed in imaginative costumes and created for the open market. In contrast, the present portrait shows a sitter with distinctive features and a contemporary style of costume, which indicates he was a known individual. Nonetheless, it is clear that in the late 18th century, this work would have been interpreted within the context of general stereotypes, particularly those linking Black sitters to primitivism and savagery.

A distinctive feature of this portrait is the lively expression of the sitter, who glances away from the viewer while softly smiling. While it was extremely uncommon for sitters in formal portraits of this period to display their teeth, it was relatively typical in depictions of Black subjects, reflecting stereotypes that highlighted bright white teeth as a distinctive trait of Black people. Many depictions of smiling Black figures appear in the background of larger compositions, often shown making eye contact with a white figure, implying a sense of obedience.

The present work is curious, therefore, as it contains elements that certainly relate to the prevailing attitudes towards race and identity in the late 18th century, yet it also reveals a quality of playful characterisation that may indicate a degree of respect by the person who commissioned it. Understanding the position of Black people within the households of the elite classes in Britain at this date is not always straightforward. Whilst most enslaved people experienced hardship, others were treated with greater respect and sometimes offered the luxury of education. However, these relationships were still rooted in power dynamics that reinforced social and racial hierarchies. Another painting that can be seen as a significant part of this tradition of Black servant portraiture is Sir Joshua Reynold’s painting of a man identified as Francis Barber, servant to Reynold’s friend, Samuel Johnson.

The identity of the artist who painted this work is currently unknown. Until recently, it was part of the renowned Veil-Picard collection formed over several generations by the Veil-Picard family. It was celebrated for its comprehensive ensemble of European Old Master paintings and works on paper, many fine examples of which have been deaccessioned at auction over the last few decades. A significant sale of their collection was staged by Christie’s in 2010, the contents of which are relevant to identifying their interest in the present work.[2] Remarkably – given the scarcity of depictions of Black subjects in art – the 2010 Veil-Picard sale included two fascinating examples; a study of two Black pages by Jacques-Andrew Portail (1695-1759) and a portrait of a mixed-race gentleman in armour attributed to Francois De Troy (1645-1730). At present, no accessible records regarding the Veil-Picard collection exist. However, we can assume that the collection took an active interest in the depiction of non-European sitters in 17th and 18th-century portraiture of which the present work can be considered a key example.

[1] We are grateful to Professor Eileen Ribeiro, Dr Hannah Williams and Jacqui Ansell for sharing their thoughts regarding the costume of the sitter in this work.

[2] Treasures of the Veil-Picard Collection, Christie’s, Paris, 23 June 2010.