We are grateful to Martyn Gregory, leading authority on the art of the China Trade, for his assistance when cataloguing this work.

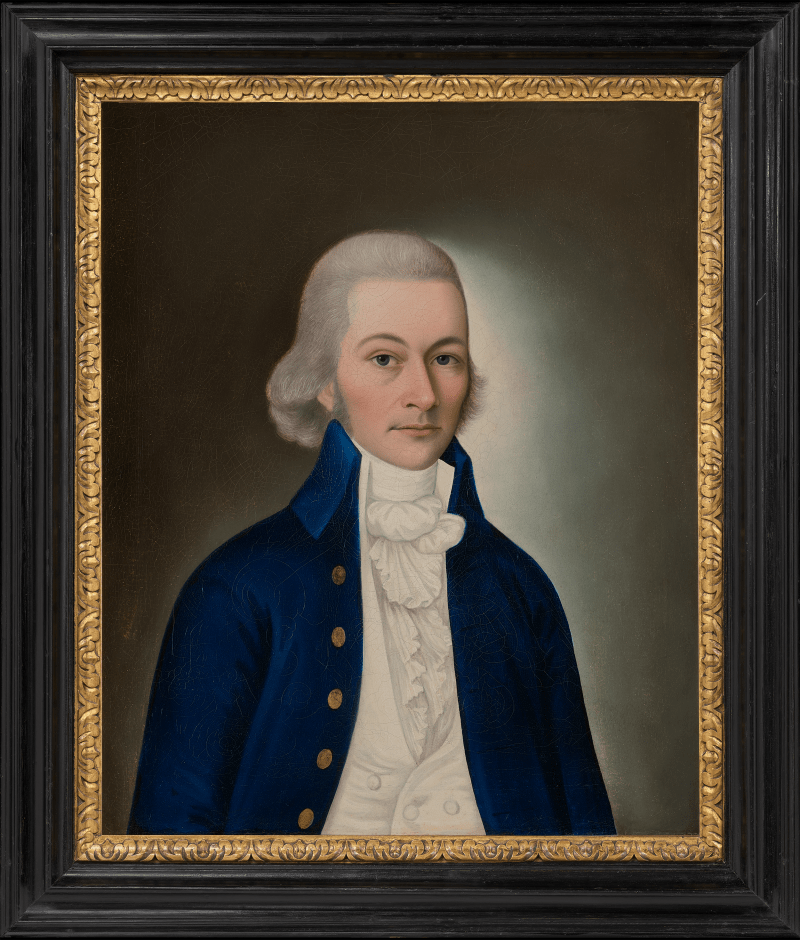

Hong merchants were central to the China trade, and maintaining relationships with them was essential for American and European traders. Painted in a distinctly western style, portraits such as this, commissioned for export, shed fascinating light on the intersection of world cultures in Canton at this date.

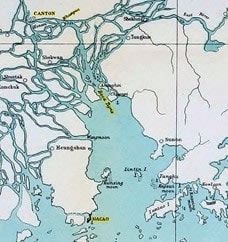

In Canton, foreign traders were required to transact through the hong merchants, who served as their intermediaries.[1] Collectively they constituted the Co-Hong—an association of around twelve merchants answerable to the emperor—charged with overseeing commerce and safeguarding China’s interests at the port. After passing through the Macao Roads and attaining the necessary permission (or chop) to sail up the Pearl River, visiting merchants would proceed past the Boca Tigris – where the chop was presented – up to the Whampoa Anchorage (fig.1). Here, any required taxes or payments (official and...

We are grateful to Martyn Gregory, leading authority on the art of the China Trade, for his assistance when cataloguing this work.

Hong merchants were central to the China trade, and maintaining relationships with them was essential for American and European traders. Painted in a distinctly western style, portraits such as this, commissioned for export, shed fascinating light on the intersection of world cultures in Canton at this date.

In Canton, foreign traders were required to transact through the hong merchants, who served as their intermediaries.[1] Collectively they constituted the Co-Hong—an association of around twelve merchants answerable to the emperor—charged with overseeing commerce and safeguarding China’s interests at the port. After passing through the Macao Roads and attaining the necessary permission (or chop) to sail up the Pearl River, visiting merchants would proceed past the Boca Tigris – where the chop was presented – up to the Whampoa Anchorage (fig.1). Here, any required taxes or payments (official and unofficial) were settled, and the captain or supercargo (chief commercial officer) onboard would engage a hong merchant. After securing a merchant and paying the necessary fees, the ships cargo was unloaded and sent on to Canton on smaller vessels accompanied by the captain and supercargo. When at Canton, the visiting traders, known the Fan Kwae (‘Foreign Devils’) by the Chinese, had to acquire the majority of their new cargo through the merchant. By the 1830s, restrictions had eased and there were more merchants with whom the traders could transact, but when the present work was painted, choice was limited. By virtue of their position, hong merchants wielded great influence, and some amassed substantial fortunes through a precarious mix of shrewd trading and the provision of credit.

The sharing of information and opinions on hong merchants was crucial to the success of trade, and numerous letters from the period survive in which the suitability of individual merchants are discussed. One trader, Dudley Pickman (1779-1846), wrote a letter to his friend Benjamin Shreve (1780-1839) of Salem, Massachusetts, who departed for Canton in 1815. The letter gave advice to Shreve based on Pickman’s experiences when he visited Canton earlier in 1805, around the time the present work was painted. Of the hong merchants, Pickman considered Houqua, for example, to be dependable, but Ponqua ‘too poor to deal with’. Chunqua was, apparently, ‘a big rogue’, and Conseequa ‘a very uncertain man’, but that ‘some of the Philadelphians are very fond of him.’[2] Despite the shaky reputations of some of the wealthy merchants, their importance was undeniable and invitations to their lavish houses were coveted by all visiting traders.[3]

The commissioning of portraits of their Chinese counterparts was an obvious way for visiting traders to show respect and preserve and improve relationships. These portraits were then exported for American and European audiences. Spoilum, whose style was heavily influenced by Western, and specifically American, portraiture, was an obvious choice of artist and some of his most celebrated works depict hong merchants (fig.2). These portraits are recognisable for their distinctive compositions which often follow a template, with the sitter shown to their waist, head turned to the left and their right hand raised, holding the bead of a necklace or another object (figs. 3). They also reveal several consistent characteristics of the artist’s style, notably the heavy, dark drawing of the sitter’s eyelids and the slight suggestion of a smile. A further defining attribute of Spoilum’s hand is the strong lighting about the sitter’s left shoulder, which is frequently observed in works throughout his oeuvre.

Over time, the identities of the sitters in most of Spoilum’s portraits of hong merchants have been lost, and the present work is no exception. From the colour and quality of his hat button, however, the sitter appears to be an official of the third, fourth, or fifth rank within the nine-grade hierarchy. His status is further indicated by the rank badge on his surcoat—each civil grade was represented by a specific bird, here most likely a goose, signifying the fourth rank. Portraits of similar ranking, unidentified officials by Spoilum exist in public and private collections around the world, indicating that there is still much research to be done on this fascinating part of the artist’s oeuvre.

Spoilum was active in Canton from around 1785 to 1810 and is considered the earliest oil painter in this region, and perhaps in China itself. Shaped by imported Western paintings and prints, he quickly became the preferred painter for visiting traders (fig.4).[4]

Although many works by Spoilum have survived, very little is known about the artist.[5] His earliest recorded work is a portrait of a man, probably Captain Thomas Fry, painted on glass and dated 1774 (fig.5).[6] This indicates that he was certainly active by the early 1770s and, in all likelihood, started his career as a reverse glass painter before adopting the medium of oils on canvas the following decade. Reverse glass painting was a thriving trade in Canton during this period, with numerous workshops producing copies of European prints on glass for the Western market. An oval portrait in oils, inscribed on the reverse ‘Spoilum/pinxt./Canton/Decr. 1st 1786’, is a touchstone work in the artist’s oeuvre and is more typical of the style of portraiture we now associate with his hand (fig.6). The oval format was evidently one favoured by Spoilum for his western sitters, and numerous examples of this type survive.[7] By this date, his style is distinctive, with his sitters' features drawn in a crisp, sharp manner.[8] That Spoilum continued to work on glass is suggested by the existence of unusual work depicting a man named George Harrison with fellow crew members from the ship Alliance, which bears a label on the reverse: ‘G. Harrisons’ – has’d of Spoilum in Canton, AD 1788.’[9] The composition derives from a print by Henry Banbury and was presumably commissioned by Harrison, who was the supercargo aboard the Alliance in 1788.[10]

The most important early written record relating to Spoilum appears in John Meares’ Voyages under January 1788. Meares describes how he had brought to Canton Chief Tianna of Atoor from the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii), who, during his stay, sat for a portrait by Spoilum, who he described as ‘the celebrated artist of China, and perhaps the only one in his line, throughout that extensive empire.’[11]

Meares was, presumably, referring to Spoilum’s use of oil paint, which distinguished him from his contemporaries in Canton who used watercolours. The portrait that Chief Tianna sat for was deemed as a success, though Meares observed that ‘…the painter had indeed most faithfully represented the lineaments of his countenance, but found the graceful figure of the chief beyond

[1] For a more complete overview of the role of hong merchants see Carl L. Crossman’s The Decorative Arts of The China Trade, (Woodbridge, 1991), pp. 15-19

[2] Crossman, 1991, pp. 29-30

[3] Crossman, 1991, p. 19

[4] Iside Carbone, Glimpses of China Through the Export Watercolours of the 18th-19th Centuries: A Selection from the British Museum’s Collection, (masters thesis, University of London, 2002), p. 27. Accessed 5 October 2025, https://soas-repository.worktribe.com/output/414961

[5] The first substantial discussion of Spoilum as a portraitist of American and English merchants and captains appeared in Carl L. Crossman’s The China Trade (Princeton, 1972)

[6] Previously with Martyn Gregory Gallery and illustrated in Crossman, 1991, pl. 3, p. 34

[7] Examples include the portraits of a member of the East India Company, c. 1800, and a man from Dorchester, Massachusetts, c. 1880, reproduced in Crossman, 1991, pl. 10, p. 45, and pl. 12, p. 48

[8] Several oval portraits by Spoilum survive on their original laminated stretchers, constructed by fusing long strips of thin wood and bending them into an oval shape over which the canvas was stretched.

[9] Exhibited in Philadelphians and the China Trade 1784-1844, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1984. Illustrated in Jean G. Lee, Philadelphians and the China Trade 1784-1844, (exh. cat., Philadelphia, 1984), cat. 208, p. 192

[10] Crossman, 1991, p. 35

[11] John Meares, Voyages made in the years 1788 and 1789, from China to the North West Coast of America … (London, 1790), p. 141. Quoted in Crossman, 1972, p. 36