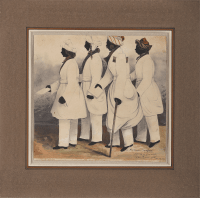

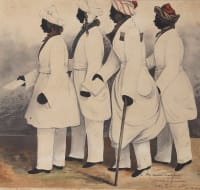

This fascinating group portrait is one of the earliest recorded depictions of Asian travellers in Britain and as such is unparalleled in British art at this date.[i] It was painted by John Dempsey, an itinerant artist who is best-known for his compelling portrayals of ‘remarkable characters’ on the streets of Victorian England. His watercolour and silhouette likenesses of the urban population offer an exceedingly rare glimpse into a social class otherwise overlooked by history (figs. 1, 2).

The present work poses many unanswered questions about the presence of Asians in Britain in the early nineteenth century and of their interactions with English society.[ii] In 1840 a group of four men in Indian clothing walking around Bristol would have been considered an extraordinary spectacle as large-scale Asian immigration would come a century later. This raises the question as to their identities.[iii] Judging by their attire, the men were probably Bengali Hindus of high caste and are likely to have been...

This fascinating group portrait is one of the earliest recorded depictions of Asian travellers in Britain and as such is unparalleled in British art at this date.[i] It was painted by John Dempsey, an itinerant artist who is best-known for his compelling portrayals of ‘remarkable characters’ on the streets of Victorian England. His watercolour and silhouette likenesses of the urban population offer an exceedingly rare glimpse into a social class otherwise overlooked by history (figs. 1, 2).

The present work poses many unanswered questions about the presence of Asians in Britain in the early nineteenth century and of their interactions with English society.[ii] In 1840 a group of four men in Indian clothing walking around Bristol would have been considered an extraordinary spectacle as large-scale Asian immigration would come a century later. This raises the question as to their identities.[iii] Judging by their attire, the men were probably Bengali Hindus of high caste and are likely to have been visitors rather than residents.[iv] They seem to be presenting papers, as though carrying out a specific mission. Between the 1830s and 1850s Britain saw an increasing number of delegations from India, variously in the fields of politics, finance, religion and science.[v] One of the earliest literary accounts of such visits is Journal of a Residence of Two Yeares and a Half in Great Britain (1841) by the naval architects Nowrojee and Merwanjee. They travelled to Bristol to learn about steam technology, carrying two letters of introduction and accompanied by their uncle-preceptor and servants. Curiously, their trip took place just one month before the present work was made.[vi] However, they were Parsis from Bombay, and a lithograph dated 1842 depicting them shows significant differences in both facial features and clothing compared to our sitters.[vii]

Although the identities of the men remain unknown, the late historian David Hansen recently proposed a compelling theory in his award-winning book Dempsey’s People (2017). The book was published to coincide with the first major exhibition of the artist’s work at the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra, which, in the late 1990s, discovered an album of the artist’s works in its collection. Hansen suggested that the four men were ‘members of a deputation visiting Bristol that year to make arrangements for the reinterment of the remains of the Hindu reformer, ecumenical religious philosopher and founder of the Brahmo Sabha movement, Raja Ram Mohan Roy, who died in the city in 1833’.[viii] Roy was a figure of great importance who laid the foundations for a long-lasting friendship between East and West and helped shape the cultural fabric of Bristol. When the Rajah died, his body was temporarily buried in the gardens of Beech House in Stapleton Grove. After ten years it was reinterred at the multi-faith Arnos Vale Cemetery.[ix] For this purpose, a special committee was set up with the support of Carr, Tagore & Company.[x] Dwarkanath Tagore (1794-1846), one of Calcutta’s most powerful entrepreneurs, commissioned the chattri memorial that still stands today.[xi] Though newspapers reported that the decision to consign the remains of the Rajah to ‘a more conspicuous resting-placel’ was taken when Tagore visited Stapleton Grove in 1842, it is suggested that our sitters were sent to Bristol as early as 1840 specifically to organise the transfer of the coffin.[xii]

Although a direct connection has yet to be established between this work and any deputation formed for the above purpose, Dempsey’s religious background, hitherto overlooked, suggests that he may have been intrigued by such a group of people. Dempsey can perhaps be considered a fluid nonconformist. He was baptised in a Moravian Chapel in Bath but married his first wife in 1819 in an Anglican Church in Bedminster. His son from a second marriage was baptised according to the rite of the Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion in 1822 and was buried nine years later in a Wesleyan ceremony at the Walcot Methodist Chapel.[xiii] This helps frame Dempsey within the context of the progressive, compassionate and inclusive social-religious ideas that were spreading in the West Country alongside Unitarianism. Significantly, this was a movement that attracted Asian travellers. Local dissenting congregations, especially Moravian ones, were known for their openness and their acceptance of Black slaves and new immigrants.[xiv] This connection reinforces our understanding of the artist’s sympathy towards outsiders and prompts a re-evaluation of his role as a reporter of multiculturalism.[xv]

The visual impact of the present work stems primarily from its use of the painted silhouette technique, a highly decorative art form of which Dempsey was a renowned exponent.[xvi] An itinerant street artist of many talents across many different mediums, Dempsey specialised in swiftly catching a likeness with delicacy and precision. Few works demonstrate this as clearly as the present work which has been highlighted with gold to add depth and lustre . According to the inscription in the lower right, this work was reportedly made in only nine minutes. Its purpose remains unknown, but the unevenly cut margins suggest it may have once been part of an album—perhaps compiled by the artist to showcase their work to potential clients—before being removed.

Like many of the ‘street portraits’ Dempsey produced at various British locations, the silhouette’s purpose is to give us a glimpse of the lives of the overlooked and the unusual.[xvii] Dempsey’s characterful subjects were typically ‘known or named individuals who dwelt in particular places, and not merely stereotypical representatives in the ‘Cries of London’ tradition’.[xviii] Although the present work does not strictly portray local people and cannot be compared to, say, Dempsey’s Black proletarian settlers such as Cotton and Charley, painted in Norwich around 1823 (figs. 3, 4), it does record ‘known characters’ and intersects with colonial ideas and ‘exotic otherness’, perhaps in response to the growing public demand for Indian visual material (the so-called ‘orientalist fantasy’). As a rare, early representation of Asians in Britain recorded in an unpatronising manner by a working-class artist, the present work is a unique survival and helps illuminate an otherwise dimly lit area of social history in Britain.

Biography

John Church Dempsey’s life is wrapped in mystery. In the words of David Hansen, he is ‘substantially unknowable, an authorial shadow behind the shades’.[xix] Despite the wealth of newspaper adverts he published in various British provincial towns, which allow us to trace his remarkable itinerary as a travelling street artist, little is known about his family, education, or, especially, his artistic training.

We do know that Dempsey was born on 2nd May 1802 in Bath to parents Edward Dempsey (1754-1826) and his wife Martha Payne. The couple married in 1788 and had only one child, baptised in a nonconformist Moravian chapel in Walcot, Bath. (His father might have been the master of St. Michael’s Poorhouse in Bath, but this cannot be ascertained.) When still a teenager, in 1819 Dempsey married an older woman from Dorset – Hagar Maber (b.1791) – in an Anglican church in Bedminster. By 1822 he was already married to another woman, Sabina Elizabeth Dempsey, with whom he had a boy called Edward John. This child was baptised according to the Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion and died in 1832.

Dempsey started his career as a portrait, miniature and landscape painter in Bath in the late 1810s. By 1821 he had already secured the patronage of ‘two families of distinction’ locally, but had also started travelling around Britain. One of his first notable commissions was the portrait of the Hon. John Thomas Thorp, Mayor of London (c. 1821), which provides early evidence of his talent for depicting facial features, temperament, and the details of clothing. He then travelled to Devon, Hampshire, East Anglia (1823), Woolwich (1824), Yorkshire and Sutherland (1825), and Durham (1826). He also visited Edinburgh, Aberdeen, Dundee, Glasgow, Dublin and Limerick, putting together a portfolio of ‘upwards of 1000 likenesses of Public Characters’.[xx]

In the mid-late 1830s, Dempsey spent some time in Manchester and Liverpool. He operated from a booth near the harbour charging a minimum of 3d. for a silhouette. His clients were mostly travellers and emigrants. One of his most characterful and larger works was a silhouette showing Members of the Liverpool Stock Exchange. After a short period in Birmingham, he moved to Bristol in 1840 and was based there for the rest of his life. His ‘Gallery of Likenesses’ moved several times (to 19-20 Lower Arcade; 18 St Augustine’s Parade; and 26 The Arcade) and offered various services, including colour mixing, framing, restoring, furniture and lighting dealerships. It seems Dempsey was settled for about five years. In 1844 he married his third and last wife, a widow from Hampshire called Sarah Neal, with whom he had been living for some years. Unfortunately, by 1845 he was bankrupt, and his property was sold at auction. It is possible that Dempsey travelled again in the 1850s, but he was back in Bristol by 1861 and had opened an artistic and photographic studio at the Upper Arcade. Two unpublished photographs from these years survive in the British Archives. He died in 1877 aged 75 while still living at 32 Upper Arcade in Bristol.

[i] Within the tradition of Indian portraiture in Britain, images of Indian people depicted with authenticity are extremely rare. Most works tend to be imagined historical scenes. The following sources have been consulted: Mildred Archer (1969) British Drawings in the India Office Library, vols. I and II. London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office; Mildred Archer (1979) India and British Portraiture 1770-1825. London: Sotheby Parke-Bernet; Pauline Rohatgi (1983) Portraits in the India Office Library and Records. London: The British Library; Patricia Kattenhorn (1994) British Drawings in the India Office Library, vol. III. London: The British Library; Pauline Rohatgi and Graham Parlett (2008) Indian Life and Landscape by Western Artists. Paintings and Drawings from the V&A 17th to the early 20th century. Mumbai: Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya; BL Print Room, Indian Portraits, Groups (19a-b).

[ii] Susheila Nasta and Florian Stadtler (2013) Asian Britain. A Photographic History. The Westbourne Press, p. 7.

[iii] The very few Indians who could be found in Bristol in the early-mid 19th century were either ‘Lascar’ seamen discharged by the East India Company or destitute servants. The fine dress of the men in the present work confirm they were neither of the above. Anthony H. Richmond (1973) Migration and Rece Relations in an English City. A Study in Bristol. London: OUP, pp. 23 and 42; Roger Kershaw and Mark Pearsall (2004). Immigrants and Aliens. A guide to sources on UK immigration and citizenship. Second edition. The National Archives. Printed by N. Rowe, Chippenham, p.11.

[iv] Carla Contractor (2015) ‘Early Indian Visitors in Bristol’, The Regional Historian: Journal of the Regional History Centre, UWE, Bristol, no. 29, p. 30. The same opinion is shared by Charles Greig, a leading historian of the art of British India, in a private correspondence (September 2024).

[v] ‘By the 1840s, Bengali businessmen, Christian converts, and students with already extensive connections to the British began to make the voyage to Britain in larger numbers. Each sought further advancement there and brought back deeper knowledge of Britain’. See Michael Herbert Fisher (2004) Counterflows to colonialism: Indian travellers and settlers in Britain, 1600-1857. Delhi: Permanent Black, p. 367.

[vi] Jehangeer Nowrojee and Hirjeebhoy Merwanjee (1841) Journal of a Residence of Two and a Half in Britain. London: William Hallen & Co., pp. 414-16. Another member of the Wadia family, marine engineer Ardaseer Cursetjee (1808-1877), published Diary of an Overland Journey from Bombay to England, and of a year’s residence in Great Britain in 1840. Cursetjee left England in November 1840.

[vii] BL P1434, Portrait of three Parsi shipbuilders: Hirjibhoy Merwanji, Jahangir Naoroji and Dorabji Muncherji, Coloured lithograph with facsimile signatures, by J R Jobbins after a drawing by W Booth. No imprint. (London, c.1840); Pauline Rohatgi (1983), pp. 115 and 150; https://parsikhabar.net/wp-content/uploads/Parsi_Silk_Muslin_Iran_India_China_Handout.pdf.

[viii] Hansen, pp. 18-19. This idea was first suggested by Carla Contractor, who recognised our sitters wearing English-style clothing typical of the Bengali elite, possibly on a pilgrimage to the tomb of their spiritual leader (from a conversation with Carla Contractor at the annual public commemoration ceremony at Arnos Vale on Sunday 29th September 2024).

[ix] For the latest study on the reburial see J. Barton Scott (2024) ‘Heterodoxies of the Body: Death, Secularism, and the Corpse of Raja Rammohun Roy’ in Comparative Studies in Society and History, 66(4), pp. 729–759. See also Bristol Mercury, 10 June 1843, p. 6.

[x] Arnos Vale Cemetery Archives, Chapel Burial Register 1839-56 , p. 5/35.

[xi] In the 1820s Dwarkanath Tagore joined Rammohun Roy’s Calcutta Unitarian Committee, which was later replaced by the Brahmo Samaj. They believed in an all-encompassing, modernised India associated with a reformed England. Their stance towards the West was one of comprehension and synthesis. They believed in an Empire based on humanitarianism, utilitarianism, and evangelicalism. When Rammohun Roy left for England in 1830, Tagore assumed the leadership of the group but lacked Rammonhun Roy’s zeal for religious reform and focused on business. From the 1830s until his death, Tagore aimed to start an industrial revolution in Bengal by being involved in a commercial bank, insurance companies, newspapers, coal mining, shipping, sugar refining, indigo manufacture, railways, tea planting, and much more. He was able to do so by associating with British partners. Among these partners, starting from 1834, were merchant William Carr and amateur artist William Prinsep. See Blair B. King (1981) Partner in Empire. Dwarkanath Tagore and the Age of Enterprise in Eastern India. Calcutta: Firma KLM Private.

[xii] Contractor, p. 30.

[xiii] England & Wales, Non-Conformist and Non-Parochial Registers, 1567-1936 and Bristol, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1938 (available on ancestry.com and findagrave.com).

[xiv] Madge Dresser and Peter Fleming (2007). Bristol: Ethnic Minorities and the City 1000-2001. Chichester: Phillimore, pp. 85-86, and p. 91.

[xv] Dempsey’s silhouette of Rev. John H. Bumby, late General Superintendent of Wesleyan Missions in New Zealand, published in c.1840, should be studied within the same context.

[xvi] Examples of Dempsey’s silhouettes can be found in private and public collections around the world. One of his best-known silhouettes is Silhouette of a little girl and dog in the Metropolitan Museum of Art [38.145.347].

[xvii] A collection of 51 British street portraits by Dempsey is in the collection at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. See David Hansen (2017) Dempsey’s People. A Folio of British Street Portraits 1824-1844. Canberra, Australia: National Portrait Gallery pp. 7-8 and 12.

[xviii] Hansen, p. viii.

[xix] Hansen, p. 12.

[xx] Hansen, p. 12.