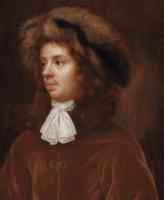

This intimate portrait of Charles was painted by Beale in the late 1650s when they were living in Hind Court, just off Fleet Street in London. It is one of her earliest surviving works and records a seminal moment when the careers of both Beale and Charles were on the ascent: Beale as a respected painter of portraits and Charles as a clerk in the Patents Office.

Beale’s portraits of Charles are not only important as works of quality that attest to her status as the most accomplished woman artist of the seventeenth century but also act as profound records of the strong bond that existed between husband and wife. They were collaborators in art, life, and business, and the fruits of this friendship were manifested in diaries, letters, poems, and portraits, such as this example.

Their relationship was unusual for the times in which they lived, insofar as it was built on mutual respect regardless of gender. Typically,...

This intimate portrait of Charles was painted by Beale in the late 1650s when they were living in Hind Court, just off Fleet Street in London. It is one of her earliest surviving works and records a seminal moment when the careers of both Beale and Charles were on the ascent: Beale as a respected painter of portraits and Charles as a clerk in the Patents Office.

Beale’s portraits of Charles are not only important as works of quality that attest to her status as the most accomplished woman artist of the seventeenth century but also act as profound records of the strong bond that existed between husband and wife. They were collaborators in art, life, and business, and the fruits of this friendship were manifested in diaries, letters, poems, and portraits, such as this example.

Their relationship was unusual for the times in which they lived, insofar as it was built on mutual respect regardless of gender. Typically, women at this date were discouraged from developing careers of their own, relying on their husbands instead to generate household income. Beale and Charles, however, believed strongly in equality between man and wife, a theme explored in her Discourse on Friendship penned in 1666.[1] In it, Beale advocated for equality in both friendship and marriage, for without equality, true friendship could not exist; ‘This being the perfection of friendship that it supposes its professors equall, laying aside all distance, & so leveling the ground, that neither hath therein the advantage of other.’ In marriage, she wrote, God had created Eve as ‘a wife and Friend but not a slave.’[2]

Beale and Charles married in 1652 and by the late 1650s they were living in a house in Hind Court where Charles kept an office and Mary had her own ‘paynting roome’. Charles was employed to process patents which were granted as royal favours to businesses and individuals. It was an advantageous post to hold, not least because he was able to survey the emerging wealth in London and build connections accordingly. Beale and Charles would entertain their friends, both old and new, at their home, and would host dinner parties, musical performances and portrait sittings.

It is not known whether Beale’s portraits from this date were painted on commission, or if they were painted as gifts for friends, but that she was respected as a painter is evident from her inclusion in Sir William Sanderson’s book Graphice: Or The use of the Pen and Pensil; In the most Excellent Art of Painting in 1658. In this publication, Beale is listed alongside several other women artists, including Joan Carlile (c. 1606-1679), Sarah Broman (fl. 1658), and a ‘Mrs Weimes’, about whom nothing is known. Graphice was published around the same time that the present work was painted, and it would therefore have been on the basis of works such as this example that the author considered her worthy of inclusion.

This work is one of a series of portraits of family members painted by Beale in the late 1650s and 1660s. They are often intimate in scale with a sensitivity seldom observed in her larger commissioned works. They are generally painted in oils on paper – canvas being a more expensive support reserved for paying customers – and were sometimes left unfinished. The present work, however, can be distinguished from this group by its completeness; it is not a quick spontaneous study of character, but an intimate, detailed recording of the likeness of a loved one.

Charles’s appointment as Deputy Clerk of the Patents in 1658 would have elevated his social status and that of his family and the present work was perhaps painted to commemorate this moment. The gold-buckled jacket, fur hat and lace collar were expensive accessories, and in an age of conspicuous consumption, they would have been irresistible signifiers of wealth and status. The same fur hat appears in other studies of Charles painted around this date.[3]

In 1665, following Charles’s departure from the Patents Office, the Beales relocated to Allbrook in Hampshire, where they remained until 1670, when they moved to Pall Mall in London. Together, Beale and Charles made a good living for the next decade; Beale painted portraits of the affluent middle class and Charles, by now considered a gentleman virtuoso through his experiments in colour making, made a healthy income as a paint supplier alongside supporting his wife.

[1] Beale’s Discourse on Friendship survives in two seventeenth-century manuscript copies, now included in British Library Harley MS 6828 and Folger MS V.a.220. The British Library copy is dated 9 March 1666 (O.S)

[2] Barber, T. (1999) Mary Beale: Portrait of a seventeenth-century painter, her family and her studio. London: Geffrye Museum, p.30

[3] See Mary Beale, Portrait of Charles Beale, c.1660, McMaster Museum of Art, Hamilton, Canada.