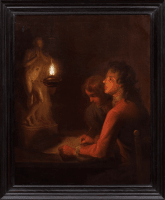

This portrait of a young artist and his companion sketching a statuette of a faun by candlelight was long attributed to Godfried Schalken, the seventeenth-century master of candlelight on account of its preoccupation with the chiaroscuro effects of artificial lighting. The technique is, however, recognisably different from Schalken’s, and although this portrait has not previously been published as a work by Seeman, it contains numerous elements entirely characteristic of his style, as well as the likeness in profile that accords well with a now-lost three-quarter length self-portrait of the same date engraved by Faber. The use of the bold red pigment – most often found in the lips of his sitters, but here employed in broad patches of colour for the artist’s coat – is a signature element of Seeman’s work, as is the heavy, emphatic folding of the drapery. The face of his brother a little further into the shade also recalls the painter’s likeness in the earlier self-portraits....

This portrait of a young artist and his companion sketching a statuette of a faun by candlelight was long attributed to Godfried Schalken, the seventeenth-century master of candlelight on account of its preoccupation with the chiaroscuro effects of artificial lighting. The technique is, however, recognisably different from Schalken’s, and although this portrait has not previously been published as a work by Seeman, it contains numerous elements entirely characteristic of his style, as well as the likeness in profile that accords well with a now-lost three-quarter length self-portrait of the same date engraved by Faber. The use of the bold red pigment – most often found in the lips of his sitters, but here employed in broad patches of colour for the artist’s coat – is a signature element of Seeman’s work, as is the heavy, emphatic folding of the drapery. The face of his brother a little further into the shade also recalls the painter’s likeness in the earlier self-portraits. For this reason, given the resemblance between the two youths, it seems likely that the second boy is one of the painter’s three brothers, most probably Isaac Seeman who pursued the same career. It is suggested that he was less prolific than his elder brother but the considerable number of works commonly attributed to Enoch, as well as their varying quality, surely makes the correct assignation of unsigned works problematic.

Enoch Seeman’s self-portraits, and indeed the earlier part of his oeuvre generally, are among the most inventive and technically brilliant of his career. Other early self-portraits – such as the example presently with Historical Portraits Limited, signed and dated to 1708 – experiment with effects of light and shade, but without the explicit light source that he employs here. Like the earlier self-portraits, this is very much a young artist’s painting, not in that it exhibits any technical deficiencies – far from it – but in that it is very plainly a performance, an exhibition to amaze the cognoscenti with his expertise.

The painting is also, of course, an interesting document of artistic training, in that it shows the young painter honing his skills by copying that perfect model, the sculpture of antiquity. The reduced-scale statuette is of a kind that proliferated in the collections of connoisseurs and the studios of painters. Sir Peter Lely, for example, can be seen holding an example of such a statuette in his Self-portrait of c.1666 (National Portrait Gallery, London), and in the canons of early modern aesthetics, there was no more beautiful or perfect conception of the human form than that achieved in classical sculpture. Fidelity to this ideal not only saved the painter from technical and anatomical error but also established him as a servant of high art and helped to assure him the status for which painters were still obliged to strive even at this late period.