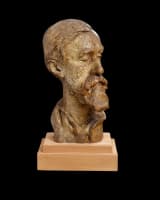

Stephen Tomlin

(1901-1937) Lytton Strachey (1880-1932)Provenance

The artist;

Julia Gowing (formerly Tomlin, née Strachey), the artist’s wife;

by family descent until 2022;

Literature

O. Garnett, The Sculpture of Stephen Tomlin. Unpublished Thesis, 1979, p. 7, no. 25b (illus. figs 94, 95);

M. Bloch and S. Fox, The Bloomsbury Stud: The Life of Stephen ‘Tommy’ Tomlin. London: M.A.B., 2023, 2nd edn, p. 246.

“The general impression is so superb, that I am beginning to be afraid that I shall find it rather difficult to live up to.” - Lytton Strachey, 1929

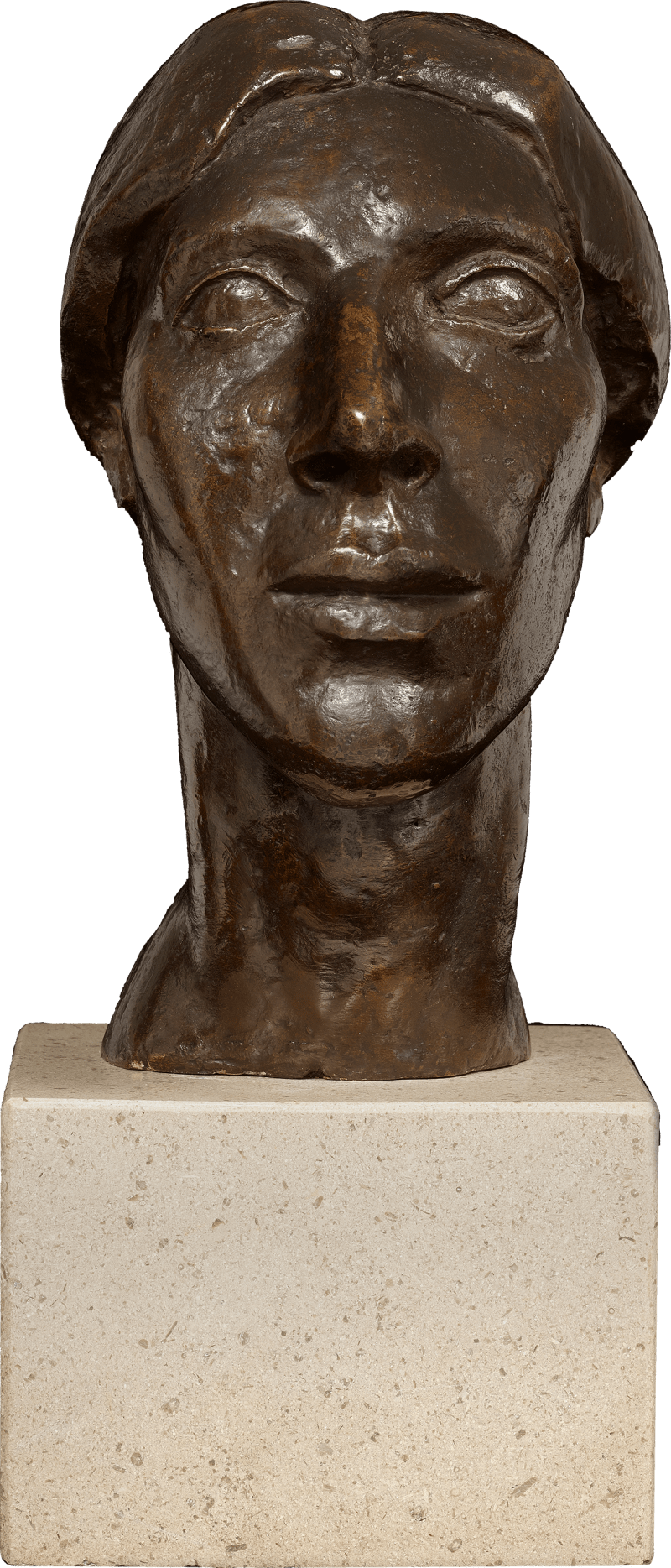

Of the principal representations of Lytton Strachey, none are as affecting as this likeness, which can be considered one of Stephen Tomlin’s masterpieces. Strachey’s expressive features, heightened by the visible marks of modelling, succeed in producing a characterisation that imparts the veneration in which Tomlin and others held him, and captures the perspicacity for which the biographer and writer was famous. The present work is the artist’s surviving plaster which resulted in three recorded casts in various mediums produced between 1929 and 1930 and was retained by the artist as a showpiece in his studio. A plaster of similar status depicting Virginia Woolf is now in the collection at Charleston and has been hand-painted in a similar manner to the present work.

Strachey was a preeminent critic and biographer...

“The general impression is so superb, that I am beginning to be afraid that I shall find it rather difficult to live up to.” - Lytton Strachey, 1929

Of the principal representations of Lytton Strachey, none are as affecting as this likeness, which can be considered one of Stephen Tomlin’s masterpieces. Strachey’s expressive features, heightened by the visible marks of modelling, succeed in producing a characterisation that imparts the veneration in which Tomlin and others held him, and captures the perspicacity for which the biographer and writer was famous. The present work is the artist’s surviving plaster which resulted in three recorded casts in various mediums produced between 1929 and 1930 and was retained by the artist as a showpiece in his studio. A plaster of similar status depicting Virginia Woolf is now in the collection at Charleston and has been hand-painted in a similar manner to the present work.

Strachey was a preeminent critic and biographer and a founding member of the Bloomsbury group. His witty and incisive prose challenged traditional hagiographic conventions of biographical writing and showcased a mastery of language that continues to inspire and influence contemporary writers. His most notable work Eminent Victorians (1918) critically examined the lives of prominent figures from the Victorian era, earning him both acclaim and contention. His nuanced and insightful observations on historical figures provided a new perspective on the human condition, contributing to broader discussions on identity, sexuality, and power dynamics in modern Britain. In the company of his Bloomsbury friends, Strachey was openly gay. In fact, Stephen Tomlin’s marriage to Strachey’s niece - Julia Strachey, also a writer - did not stop the two men from engaging in a romantic relationship and subsequent lifelong friendship.

By 1929 Tomlin was revered by his Bloomsbury friends. He had become a favourite guest at three of their country houses – Hilton Hall near Cambridge, where David Garnett moved after achieving success as a novelist; Charleston Farmhouse in Sussex, home to Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant; but above all Ham Spray in the Wiltshire Downs, where Lytton Strachey lived with the artist Dora Carrington and her husband Ralph Partridge, and where Lytton sat for the present likeness.[1] Both Strachey and Carrington had fallen in love with Tomlin, who appears to have reciprocated their feelings and frequented their countryside idyll throughout the late 1920s. Two years prior to the completion of this bust, Strachey wrote to Tomlin: ‘Dearest Tom Cat, I am always, your Lytton.’[2]

The summer of 1929 at Ham Spray was one of private parties and industrious artistic activity, including the making of home movies involving Tomlin and friends. Somewhat akin to Charleston Farmhouse in its decorative allure and endless parade of visitors, Ham Spray became a crucial point of artistic exchange amongst the extended Bloomsbury group. Tomlin spent most of the summer there in 1929 with his wife Julia Strachey and was invited by Lytton Strachey to stay at the house for an additional two weeks after Julia left to produce the present likeness. Having entrusted Tomlin with an advance payment of £30 the previous year in December 1928, Strachey was now understandably eager to see the work started.

While Carrington painted in her studio above the former granary, Strachey sat for Tomlin. In the evenings, they met with other guests in the music room, where they played the piano, listened to music, and danced to songs on the gramophone. Although Strachey’s account of the sittings was distinctly circumspect - ‘I sit all day to Tommy, who is creating what appears to me a highly impressive, repulsive, and sinister object.’ [3] – the final result delighted him: 'The general impression is so superb, that I am beginning to be afraid that I shall find it rather difficult to live up to.'[4]

In celebration of Tomlin’s triumph, Strachey held a private unveiling party with the purpose of corralling ‘the influential inhabitants of Bloomsbury to come and look’.[5] A finished example, cast in either bronze or lead, was displayed in his sitting room and David Garnett’s glowing review of the evening paints a picture of pride on Strachey’s part, and exceptional ability on Tomlin’s:

I went round to Lytton's room & found him laying out sherry glasses & stuffed olives; I had chanced on a private view of his bust which I think is the most distinguished & accomplished head you have ever done.[6]

Three casts of Lytton’s likeness by Tomlin from this period have survived, although the lack of surviving documents relating to his workshop practices makes the order of their production difficult to establish. We do know that in 1930 Lytton lent his bronze cast to an exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in London where it was acquired by the connoisseur and collector Richard Brinsley Ford, who donated it to the Tate after Lytton’s death in 1932.[7] The Tate cast is recorded as being the second from an edition of three, the third, which is numbered, being owned by Lytton’s sister Philippa before passing by descent to her nephew Richard who sold it in 1975.[8] It seems likely that the latter work was in fact owned by Lytton initially and was possibly made to replace the bronze sold at the Leicester Galleries exhibition. A further cast in lead was owned by David Garnett. The present cast in plaster was kept by Tomlin until his death in 1937 and was later used in 1973 by Anthony D’Offay Gallery to cast a new edition of eight bronzes, one of which is now in the collection at Charleston.

[1] M. Bloch, Bloomsbury Stud: The Art of Stephen Tomlin. London: Philip Mould & Company, 2023. Available at: www.philipmould.com/exhibitions

[2] L. Strachey, Letter to S. Tomlin. September 1927. Julia Strachey Papers, UCL Special Collections, D2.

[3] L. Strachey, quoted in O. Garnett, The Sculpture of Stephen Tomlin. 1979.

[4] L. Strachey, Letter to S. Tomlin. September 1929. Julia Strachey Papers, UCL Special Collections, D2.

[5] D. Garnett, Letter to Stephen Tomlin. 1 December 1929, Julia Strachey Papers, UCL Special Collections, D3.

[6] D. Garnett, Letter to Stephen Tomlin. 1 December 1929, Julia Strachey Papers, UCL Special Collections, D3.

[7] Tate, reference N04616.

[8] Sold at Sotheby’s, 12 November 1975, lot 11.