The blossoming career of Cedric Morris

Four decades after his death, is the artist finally getting the recognition he deserves?

By Alec Marsh, The Spectator Magazine

In the winner-takes-all world of modern art, there’s every chance you might not have heard of Cedric Morris. Why should you? No matter how much you sweeten the tea, the Welshman, born in 1889, was no Pablo Picasso, Mark Rothko or Salvador Dali. Nor from our 21st-century outlook can it be said that the name itself inspires much confidence: ‘Cedric’ sounds about as on-trend as a character from a short story by Saki, and when paired with Morris, the combination offers up all the avant-garde promise of a baked camembert starter at an Aberdeen Angus steakhouse.

But don’t be put off, because there’s more to Morris than meets the eye (or ear) – something you’ll discover if you venture to Berwick-upon-Tweed this summer for a small but ambitious exhibition that seeks to offer a primer on the life and work of a man who might just qualify as Britain’s least well-known well-known artist.

The first painting that greets you as you arrive at Cedric Morris: Artist, Plantsman and Traveller is a commanding, larger-than-life self-portrait from 1941. The composition could almost be a selfie: Morris’s wavy hair appears to merge into the background, while the focus of the picture is the eyes. Windows into a man’s soul, said Elizabeth I – well, you could look all day and still not fathom it, but the intensity is unmistakable.

This is one of three Morris portraits carefully selected for this show – though the one that will inspire most attention, I suspect, is his luminous portrait of a young Lucian Freud, which comes near the end. Freud was Morris’s student at the art school he ran from his house, Benton End, outside Hadleigh in Suffolk, and he sat for him when he was 19 in 1941. Highly textured and overly surreal in colouring, the portrait is all luxuriant hair, competing surfaces offering an impression of dynamic taciturnity – and it’s captivating. (Freud loved it, telling Stephen Spender that it was ‘absolutely amazing’: ‘It is exactly like my face, [it] is green, it is a marvellous picture.’)

But it is not primarily for his portraits that I suspect that Morris is known today, to those that actually do know him. Rather it’s for his flowers. And this where the curator of this exhibition has sought to put Morris’s life as a plantsman into the spotlight. He grew thousands of irises and bred 90 varieties of the flower at his gardens in Suffolk – flowers which, along with lilies, often featured in his works. One of these on show at Berwick is the spectacular ‘Iris Seedlings’ (1943), a fanfare of blue, purple, white and yellow irises in a golden vase standing on a mauve table against a beige backdrop dominated by one of his own landscapes. The flowers themselves have a super-real, almost anatomic quality and the brushwork brings to mind the later work of Lucian Freud, which isn’t altogether surprising. To my mind it’s particularly apparent on the blooms in the adjacent flower painting, ‘Helen’s Pot’, where the subject looms against a mottled green, grey and brown background. As Morris said: ‘Good flower painting must show a great understanding between painter and painted otherwise there can be no connection and truth.’

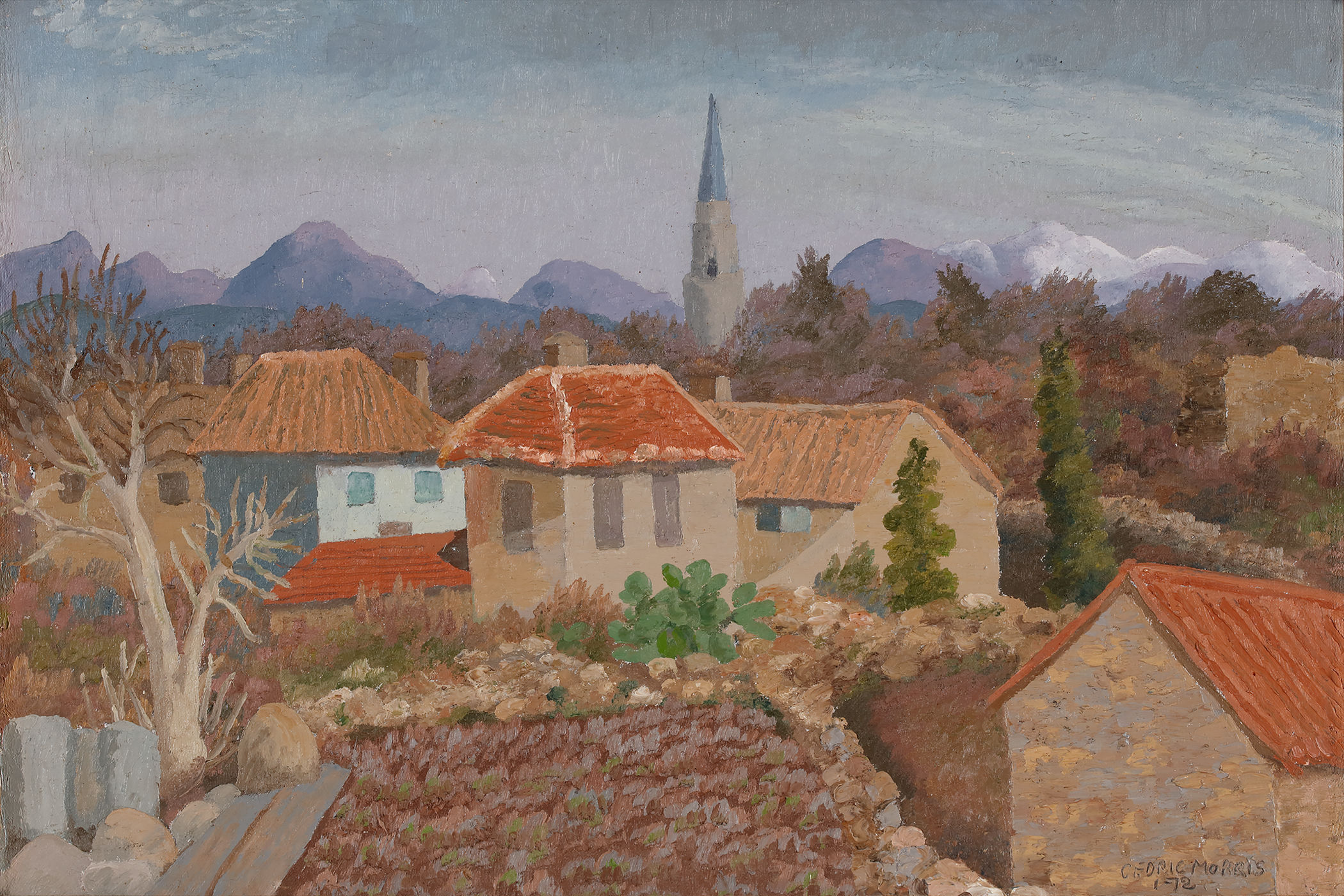

As well as portraits and flowers, Morris’s mature works covers birds and landscapes. The Berwick show has scenes from his travels to Mexico and Turkey (as late as the early 1970s, shortly before he stopped painting because of failing eyesight in 1975). With their high horizons, undulating hilltops, flattened planes and his distinctive decorative brushwork, these are peculiarly tranquil though rather lonely landscapes. As the curator of the show, James Lowther, points out, there are no people in them. It contributes to a strange, almost lifeless stillness.

Which is so unlike his depiction of flowers, or indeed birds. Morris was an animal lover (he named a variety of iris ‘Benton Rubeo’ after his pet macaw) and was an environmentalist before it was a recognised category. And as a result birds – fiercely lively looking things – were a theme of his. They were united with his passion for flowers in one of the stars of the Berwick show, ‘Crisis’ (1938), which was Morris’s reflection on the gathering storm of world affairs at the time. Nine birds, including a sinister-looking hawfinch (I think) and what is possibly the most evil green woodpecker imaginable, represent Europe’s leaders (Morris never said which was whom). They are set against a macabre landscape – more Mordor than Suffolk – featuring fading blooms of a Jersey lily, a flower associated to a degree at least with death, and yellow evening primrose, itself associated with inconsistency. Once again there is more going on here than first meets the eye.

It’s clear that in the rural idyll of Suffolk (where he moved in 1928 with his partner of 60 years, the painter Arther Lett-Haines), as well as growing irises and having pupils such as Freud and Maggi Hambling, Morris found his own way of seeing the world. And it’s patently a way of seeing that still speaks to us and which was not without its influence, in its day or in ours.

And who knows, what with Berwick’s show and with an exhibition [Garden To Canvas: Cedric Morris & Benton End] that runs until Wednesday at Philip Mould’s gallery in London, perhaps this is Morris’s moment to shine, 43 years after his death. It’s about time.