‘At The Flower-Pot Over the Balcony’:

The Location of Mary Beale’s Studio on Pall Mall

By Valeria Vallucci

Discovering that Mary Beale lived and worked above our gallery has been one of the highlights of the past year. It added a delightful frisson and relevance to our long-planned exhibition Fruit of Friendship: Portraits by Mary Beale, which ends on 19th July. The original walls of Mary Beale’s ‘payinting roome’ may have gone, but she will always be part of our genius loci.

We are particularly indebted to Dr. Helen Draper, contributor to our catalogue, who carried out the first in-depth study of Beale’s professional studio and identified its precise location [1]:

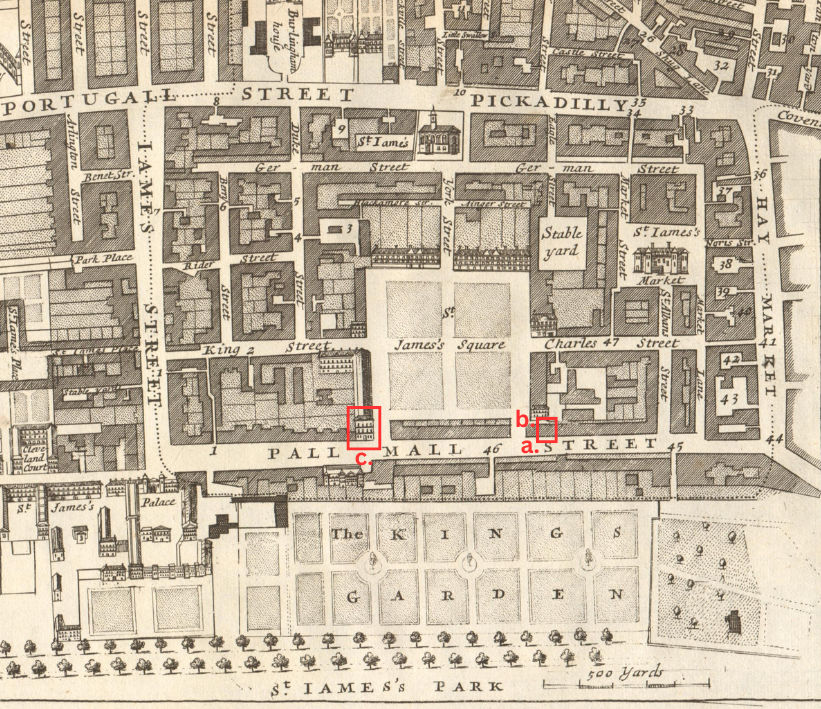

In her thesis Draper writes: “There is at present a nineteenth-century, four-bayed building to the right of the corner house consisting of a basement, ground floor and five stories above it, including an attic with dormer windows. This plot [marked box ‘a’ on the map above] almost certainly […] encompassed the ‘ground of 22 Foot in Front in the Pell Mell Feild [sic]’ where cousin Symonds built the Beales’ house.”[2] The spot is exactly where the Philip Mould Gallery now stands: 18-19 Pall Mall.

To reach this conclusion, Draper used a wide variety of sources, including taxation records, ground plans and letters, three of which were crucial. One was addressed to ‘Charles Beale Esqr at his house the next doore to the Golden Ball in Pell-Mell’ while the other two were sent to local goldsmith and banker David Willaume ‘a la Boulle Dor sur le Pellemelle a Londre’ and his apprentice ‘next to St James’ Square’. Taken together, the three letters helped Draper locate the sign of the Golden Ball ‘next to St James’ Square’ and Beale’s studio ‘at or just beyond the Square’s eastern entrance.’[3] By counting the number of residences on the north side of Pall Mall between the house of royal mistress Mary Davis [box ‘c’ on the map above] and the Beales, Draper confirmed that the Beales’ house was ‘closer to the east end [of the street] than the west’, and was next door to the corner plot [marked ‘b’ on the map above] occupied by Willaume.[4]

Draper’s groundbreaking research inspired us to investigate further and drew our attention to the fascinating world of traders’ signs. As The Book of Pall Mall puts it, the north side of Pall Mall reflected ‘more freedom of architectural choice’ because, unlike the south side, it was not Crown land. It also featured ‘fewer family houses and more building of a commercial nature’.[5] When the Beales moved to the potentially profitable north side in 1670, Pall Mall was already known for its frenetic tavern clubs. It soon started filling up with coffee and chocolate-houses, and luxury shops ‘geared to women’s wishes’.[6]

To identify and advertise themselves, businesses would hang a painted board or a carved and gilded emblem outside their premises. Traders’ signs functioned as addresses before the numbering of streets and became compulsory under Charles I. They were visible from far away, which was particularly helpful for those who could not read. Some of these signs were hung across the streets reaching ‘gigantic proportions’ and often ‘creaked and groaned’ when it was windy, but their size was reduced during the reign of Charles II.[7] This eighteenth century image of Cheapside gives an idea of how shop signs influenced the look of commercial London streets such as Pall Mall:[8]

As Pall Mall was newly paved, and the corner near St James’s Square newly built, the signs would also have been new. They therefore reflect the early commercial and social environment in which Mary Beale thrived. One of her neighbours was Henry Pert, an art dealer and copyist who lived and worked near the Beales from the late 1670s.[9] He could be found ‘next door to the sign of the Royal-Oak’, which was probably a tavern.[10] The royal bookbinder and bookseller William Nott lived a few doors to the right from the late 1670s and remained there for about twenty years.[11] His address was ‘at the King and Queen’s Arms in the Pall-Mall’.[12] Daniel Malthus, an apothecary and neighbour from the late 1680s, was further down the street ‘at the Pestle and Mortar in the Pall-Mall’.[13]

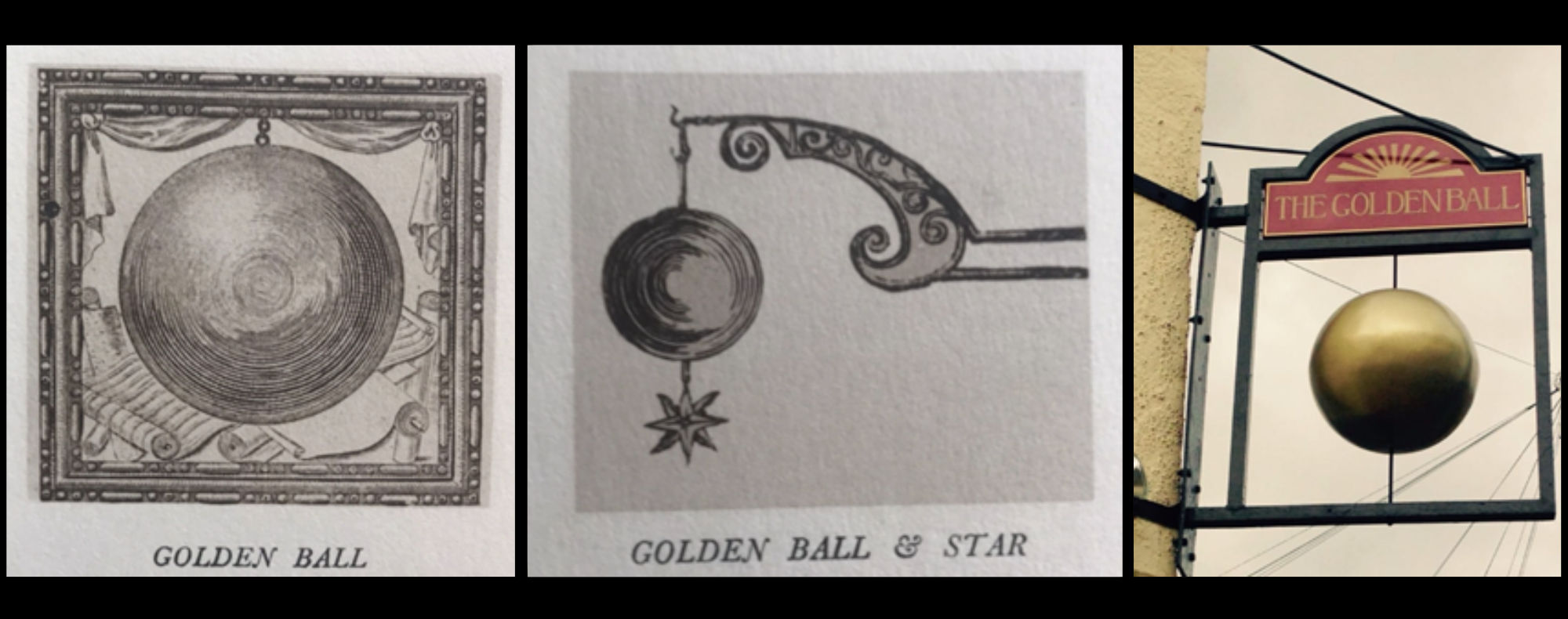

The letter above mentions that the Beales’ home and studio was ‘next door to the Golden Ball’ sign. There were several Golden Ball signs in St James’s which probably looked like variations of these:

The Golden Ball was a common sign – made of metal and suspended from an iron bar fixed above or near the door – traditionally associated with mercers (textile traders). Simple in shape, its origin lies in Constantine the Great’s regal insignia. In the Middle Ages, when most silk was imported from Byzantium, silk mercers adopted Constantine’s golden globe as their sign.[15] We can assume that before the goldsmith Willaume took over the shop around the corner from St James’s Square and adopted the sign of the Golden Ball in the late 1690s, there must have been a silk mercer (or similar) next door to the Beales’ house.[16]

We have recently found something else that helps us locate Beale’s home and studio. It comes from the Advertisements column of the London Gazette from January 1686. Someone lost a gold watch in St. James’s area: “Whoever brings into Mr. Beales in the Pall-Mall, at the Flower Pot over the Balcony, or to Captain Moons, in great St. Helens in Bishopsgate-Street, shall have two Guineas reward, or if any one can give notice where it may be had he shall be well rewarded”.[17]

We do not know if the unfortunate watch owner was a friend or a client of the Beales, but it is interesting to note that, in this case, the Beale’s studio was considered a safe place to store jewellery. This adds another dimension to our knowledge of the Beales’ business. Not only was it well signposted on the London map, but it was considered friendly, socially responsible and open enough to be a commercial facility receiving valuable deliveries and perhaps even for securely holding luxury items for short periods.

Meanwhile, the Beales’ new address – ‘at the Flower Pot over the Balcony’ – opens another dimension to the story of the studio’s location. The advertisement tells us the Beales were at the Flower-Pot over the Balcony, next to the Golden Ball. A sense of height thus enters the picture. The Beales’ business seems not to have been at street level, but on or above the first floor, perhaps at the level of the balcony, probably on the first or second floor of their four-storey town house. As Draper suggests, Beale’s painting room was ‘almost certainly in her case the “great Garrett”’.[18] The sign above the balcony may have helped customers understand the distinction between their living and commercial space.

Balconies were first introduced to fashionable London in the 1650s and 1660s and were also used ‘in the place of signs.’ When they become increasingly widespread towards the end of the century, further elements were added in terms of material and colour.[19] There were several balconies on Pall Mall at the time: a ‘blue balcony’ on the Haymarket side;[20] a ‘carved balcony’ on the corner of St Alban’s Street from 1666; [21] and an ‘iron balcony’ on the south side of Pall Mall a few doors from Delafoy’s Chocolate House.[22] Unfortunately, we have not found any details of the Beales’ balcony, but we can guess it was pleasantly adorned and functioned as a ‘shop window’. Perhaps, in fine weather, Mary Beale’s portraits of famous people were displayed on the balcony, together with drapery or tapestry, to advertise her services as a painter. It was not uncommon for dealers to hang pictures on their balconies. (Inevitably, they sometimes blew away![23]). Shown at height, Beale’s portraits would certainly have caught the eye of the many royals and aristocrats heading to the Palace or to St James’s Square.

Could the balcony be the one visible in Johannes Kip’s engraving (1710) circled in blue in the image below? This is the building Draper suggests was Beale’s home and studio:[24]

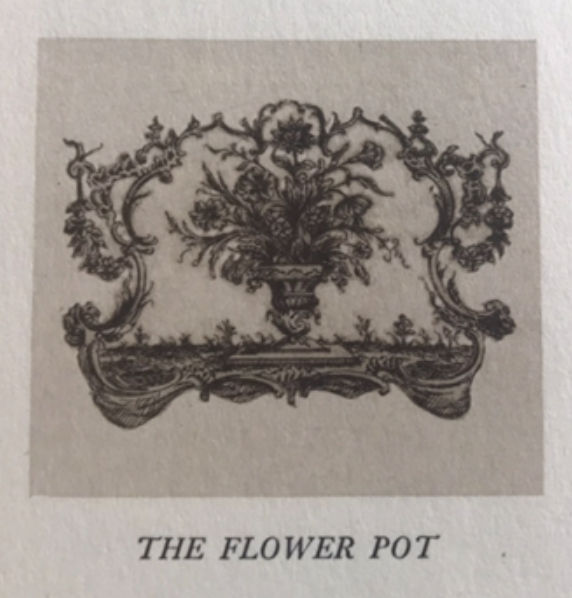

Whether it was made of iron or coloured red, blue or green, this balcony was evidently decorated with the ‘Flower-Pot’, another traditional traders’ sign common in old London.[25] The Flower Pot was originally a sign for earthenware dealers, but it was later used by seedsmen, apothecaries, perfume sellers, and others.[26] If Mr. Beale was to be found at the Flower Pot over the Balcony,does this mean Mary Beale used the Flower Pot as her trading sign?

The symbolism of the Flower Pot is also fascinating for it was associated with the vase of lilies ‘symbolical of Our Lady’.[27] Some of its meanings are explained in a note to a collection of seventeenth-century letters edited by Sir Edward A. Parry (1863-1943) and reported in a mid-twentieth century story:

[…] In the classic edition of her Letters, edited by Edward Abbott Parry, he has an interesting note about the shop at the sign of “The Flower Pot”, where Dorothy wanted to procure a quart of orange-flower water. He says there were several “Flower Pots” in London at that time. “An interesting account of the old sign,” he goes on, “is given in a work on London tradesmen’s tokens, in which it is said to be derived from the earlier representations of the salutations of the Angel Gabriel to the Virgin Mary, in which either lilies were placed in his hand, or they were set as an accessory in a vase. As Popery declined, the angel disappeared, and the lily-pot became a vase of flowers, subsequently the Virgin was omitted, and there remained only the vase of flowers.”![28]

An 1844 article in The Archaeological Journal tells us the flowerpot sign was also rooted in old rural religious imagery: “Often the lily-pot occurs as an emblem of the Virgin, as at Woodbridge St. Mary, Suffolk, where it fills a panel on the stem of the font, and at Erpyngham St. Mary, Norfolk, carved on the tower, whilst at Cowfold, Sussex, it is on the canopy above the site of an altar.”[29]

Was the Flower Pot Mary Beale’s personal sign? Did she link her art with allusions to her own name and to the Virgin Mary she first admired in Suffolk? Typically, painters’ signs were the Golden Head, St Luke’s head, the Golden Pallet, and sometimes the King’s Arms.[30] But the Flower Pot more appropriately publicised a family business led by a lady painter called Mary (who signed herself as Maria) and by her husband, who also offered quasi-scientific services (similar to those of an apothecary or a perfumier) such as pigment making.

To conclude, in the middle of Pall Mall, on the north side, at the sign of the Flower Pot, above the Balcony, next door to the Golden Ball opposite St James’s Square, the extraordinary Mary Beale welcomed her clients. And more than three hundred years later, the Philip Mould Gallery proudly continues to honour her memory.

[1] Helen Draper (2020) ‘Mary Beale (1633-1699) and Her “Payinting Roome” in Restoration London’. Unpublished PhD thesis. University of London, p. 318. Available at: https://sas-space.sas.ac.uk/9344/1/DRAPER%2C%20H%20-%20THESIS%20-%20Mary%20Beale.pdf (Accessed 25/06/2024).

[2] Samuel Symonds was both the constructor and the landlord to whom the Beales paid their annual rent. Draper, p. 178.

[3] Draper, p. 177.

[4] Ibid.

[5] J.M. SCOTT (1965) The Book of Pall Mall. London: Heinemann, p. 19.

[6] E.J. BURFORD (1988) Royal St James’s. Being a Story of Kings, Clubmen and Courtesans, London: Robert Hale, pp. 79 and 84.

[7] Cecil A. Meadows (1957) Trade Signs and Their Origin. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp. 3-4.

[8] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ONL_%281887%29_1.319_-_Bow_Church_and_Cheapside_in_1750.jpg

[9] Westminster Archives, Poor Rate (Overseers’ Accounts), St Martin-in-the Field, M/F 1556, vol. 405, p. 167.

[10] London Gazette, May 5, 1698-May 9, 1698 (all periodicals and newspapers mentioned in the notes are available online in the Burney Newspapers Collection through subscription).

[11] Westminster Archives, Poor Rate (Overseers’ Accounts), St Martin-in-the Field, M/F 1556, vol. 405, p. 167; Parish Records (Overseers’ Accounts), St James’s, M/F 650, vol. D11, Pall Mall North.

[12] London Gazette, June 29, 1682 - July 3, 1682; June 19, 1684 - June 23, 1684.

[13] London Gazette, February 10, 1687 - February 14, 1687.

[14] https://www.yelp.com/biz_photos/golden-ball-bishophill?select=INAdHstCvRepWb0AUQ3NLg

[15] Jacob Larwood and John C. Hotten (1908) The History of Signboards, from the Earliest times to the Present Day. London: Chatto & Windus, p. 482. Available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/45249 (accessed 26/06/2024).

[16] “Mr. David Williams, French goldsmith, at the Golden Ball in the Pall-Mall”. See London Gazette, November 4, 1697- November 8, 1697.

[17] London Gazette, January 11, 1686 - January 14, 1686.

[18] Draper, p. 183.

[19] Jacob Larwood and John C. Hotten (1951) English Inn Signs. Being a Revised and Modernised Version of History of Signboards. London: Chatto and Windus, p. 225.

[20] Post Man and the Historical Account London, England, October 29, 1702 - October 31, 1702.

[21] E.J. BURFORD (1988) Royal St James’s. Being a Story of Kings, Clubmen and Courtesans London: Robert Hale, p. 101.

[22] Post Man and the Historical Account, July 3, 1701 - July 5, 1701.

[23] Daily Courant London, March 8, 1707.

[24] DRAPER, p. 319.

[25] Daily Courant, July 31, 1717 and November 16, 1727.

[26] Meadows, p. 86.

[27] Larwood and Hotten (1951), pp. 32, 93,

[28] Esther Meynell (1946) Cottage Tale. London: Chapman & Hall. Available at: https://www.fadedpage.com/showbook.php?pid=20201140 (accessed 27/06/2024).

[29] British Archaeological Association (1844) The Archaeological journal. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longman, p.173. Available at: https://archive.org/details/archaeologicaljo55brit/ (accessed 25/06/2024).

[30] Meadows, p. 104.