Charles Beale, Man of the City (1658-1665)

By Valeria Vallucci

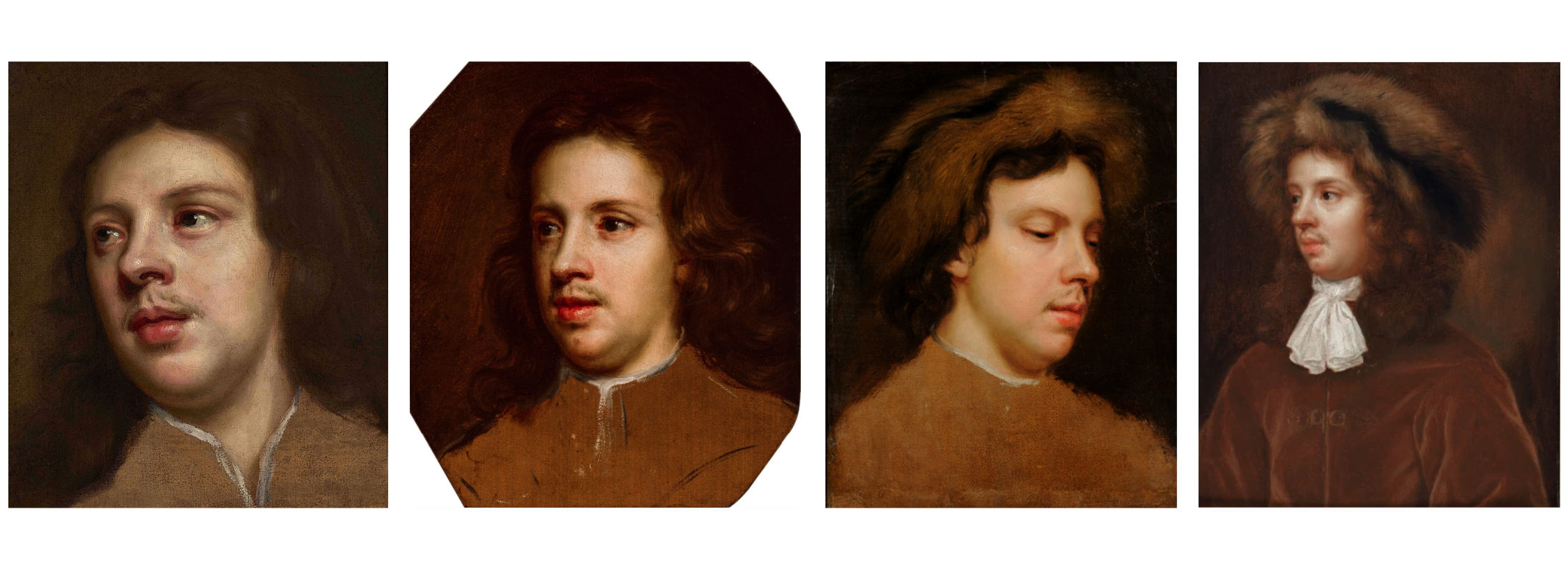

Mary Beale, Charles Beale (1631–1705), late 1650s (Philip Mould & Company).

A highlight of our current exhibition Fruit of Friendship: Portraits by Mary Beale is a portrait of Charles Beale from the late 1650s. It is one of the earliest surviving works by the young Mary Beale.

The portrait is part of a series of intimate studies of family members painted in the late 1650s/early 1660s when the artist was busy honing her skills in an affordable medium. Charles was evidently a willing sitter, judging by the number of studies of him that have survived.

The present portrait is unique within this group for its sensitivity and completeness – the other examples show only the head with the body left unresolved. Looking carefully at the four portraits shown above, we see the artist widening her focus to present a final, more polished portrait of Charles.

Wearing an expensive-looking outfit complete with a fur-brimmed hat, he looks like a man on the up. Except for his white cravat, knotted quite tightly around the neck, the picture is a feast of silky browns. The richness of the velvet, the softness of Charles’s shoulder-length hair, and the fine fur against the dark background combine to convey an impression of status. In early 17th century Dutch portraiture, the beaver hat signified prosperity. However, in Restoration England, where the poor rodents had already been hunted to extinction, the beaver hat became ‘a recognised object of national fashion’ and was no longer considered ‘an item of utmost wealth and luxury.’[1] It remained, however, an expression of social aspiration – something to wear on special occasions, at church, or out for dinner where one would be seen.[2]

In truth, up until this point, Charles had yet to find his path in life. He had married young without a substantial inheritance and left university without completing his studies. He then turned to manufacturing pigments for the Covent Garden art scene but struggled to support his family. Nevertheless, he was by all accounts friendly, responsible, and keen to do good. These qualities, together with his family’s fine reputation in the civil service, were enough to earn him the appointment of Deputy Clerk of the Letters Patent in 1658. The Beales must have felt that this was the first concrete step towards success for both of them, and we can guess that Mary painted our picture in a mood of joy and optimism.

Charles’s new job came with spacious accommodation in Hind Court (off Fleet Street) and an adequate salary. They made new friends and connections and a second baby soon followed. As Helen Draper states, “in terms of the house they lived in and their taxable prosperity”, the Beales were now “on an economic par with the wealthier merchants and professionals among their neighbours.”[3] In these favourable new circumstances Mary’s art flourished and her determination to become an accomplished painter grew.

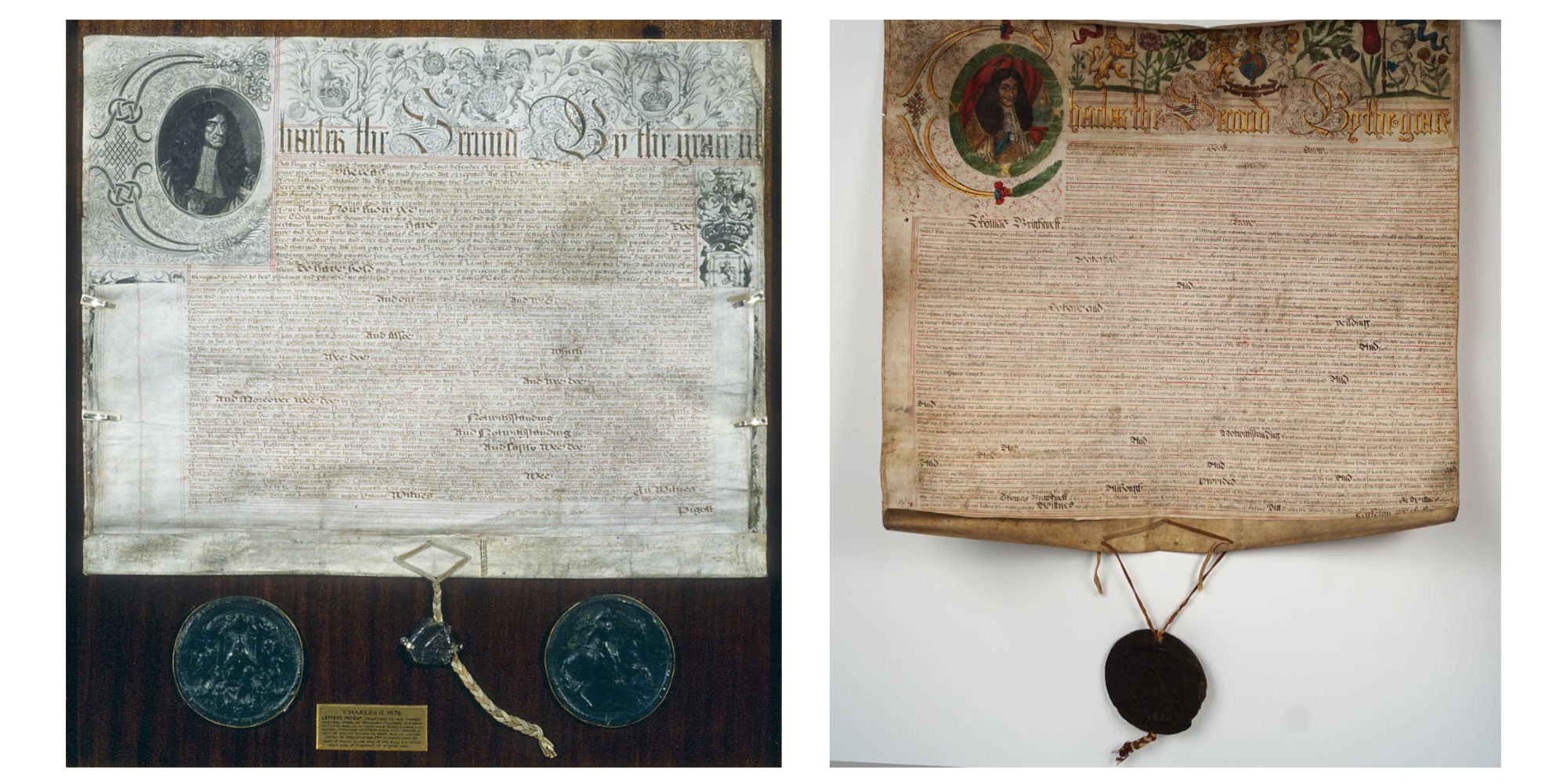

Whilst Mary divided herself between family and portraiture on the top floors of their new home, Charles prepared and supervised the production of letters patent from a busy office downstairs. Letters patent were open documents issued by the king granting various privileges, such as trading licences, land rights, and appointments to royal or civil offices. Though he had artistic flair, Charles did not dislike such administrative tasks, and as Deputy Clerk, he enjoyed some power. He was a middle-management figure in a bureaucracy that processed the king’s grants (known as warrants or bills) to the point where they obtained the Great Seal and became lawfully effective. Because the procedure was long and convoluted, involving various offices of the Court of Chancery, Charles could speed-up, slow, or stop the process. He could seriously affect potential patentees’ careers and finances.[4]

Examples of letters patent approved under the Great Seal of Charles II [5]

Some Chancery senior officers became his mentors and, eventually, clients of Mary. These included William Trumbull senior (1603-1678) at the Signet Office in Whitehall, for whom Charles would have prepared dockets (short summaries) for review; the Solicitor-General Sir Heneage Finch (1620-1682), one of the main law officers of the Crown, whose signature was essential for the passing of the king’s warrants; Edward Hyde (1609-1674), Lord Chancellor and Keeper of the Great Seal, whose office at Worcester House Charles visited with patentees for final approval before receiving the Great Seal; and Sir Harbottle Grimston (1603–1685), Master of the Rolls on Chancery Lane, where Charles would have sent letters patent for enrolment (copies for administration).

Similarly, officers, merchants, churchmen, and landowners, who often called on Hind Court to receive engrossed (finalised) letters patent, became familiar with the Beales’ collection of art, and with Mary’s style of painting. It is very likely that Charles hung a few portraits in his office purely for ‘marketing’ purposes.

Life in the City was by no means just work. Fleet Street was a buzzing main artery of the city, perhaps not always suitable for a respectable young family but providing great excitement. For instance, the Beales could not have missed the famous cavalcade of Charles II on 22nd April 1661. One of the temporary baroque triumphal arches, The Garden of Plenty, was erected just opposite the gate to Hind Court. For the occasion, Charles may even have worn the brown velvet coat we see in our portrait.

Dirck Stoop (c.1610–c.1686), Charles II's Cavalcade through the City of London, 22 April 1661.

Museum of London.

In this stimulating environment, the Beales built a supportive and nurturing network of friends and family, who often visited Hind Court, sometimes with a venison pie in hand, for entertaining soirees of music, art, and, on occasion, a little uplifting religious dogma. The Beales made some of their most durable friendships by attending lectures at the City churches, where we can picture Charles dressed as in our portrait. The couple were members of St Dunstan-in-the-West, where their son Charles Jr was baptised and Dr. William Bates (1625-1699) was the vicar until 1662. They would have met John Wilkins (1614-1672), rector of St Lawrence Jewry, where John Tillotson (1630-1694) was also a lecturer (when not preaching at the Lincoln’s Inn Chapel). They may also have befriended the young and popular Edward Stillingfleet (1635-1699) at the Rolls Chapel, where he preached before moving to the much larger St Andrew’s in Holborn. These religious men became friends for life – and some of Mary’s most famous and recurrent sitters.

Close family members were not far away either. Aside from the Woodfordes, who sometimes lived at Hind Court, the Smith cousins were just a few minutes away at Temple, Charles’s older brother lived in Hatton Garden, and Samuel Woodforde’s sister on Bassinghall Street – on the way to the Royal Society in Broad Street.

At the very inception of this exciting new chapter of her family life, the young and loving Mary painted our bust of Charles Beale in his fur hat. Could her proud husband have kept this picture in his office to intrigue and amuse the officers and patentees of the Restoration? To inspire adventurers and merchants of the newly granted royal charters in their quest for foreign gold, timber, and other furs? We will never know. What we do know is that the portrait represents the formidable strength of the artist’s faith in her husband’s potential.