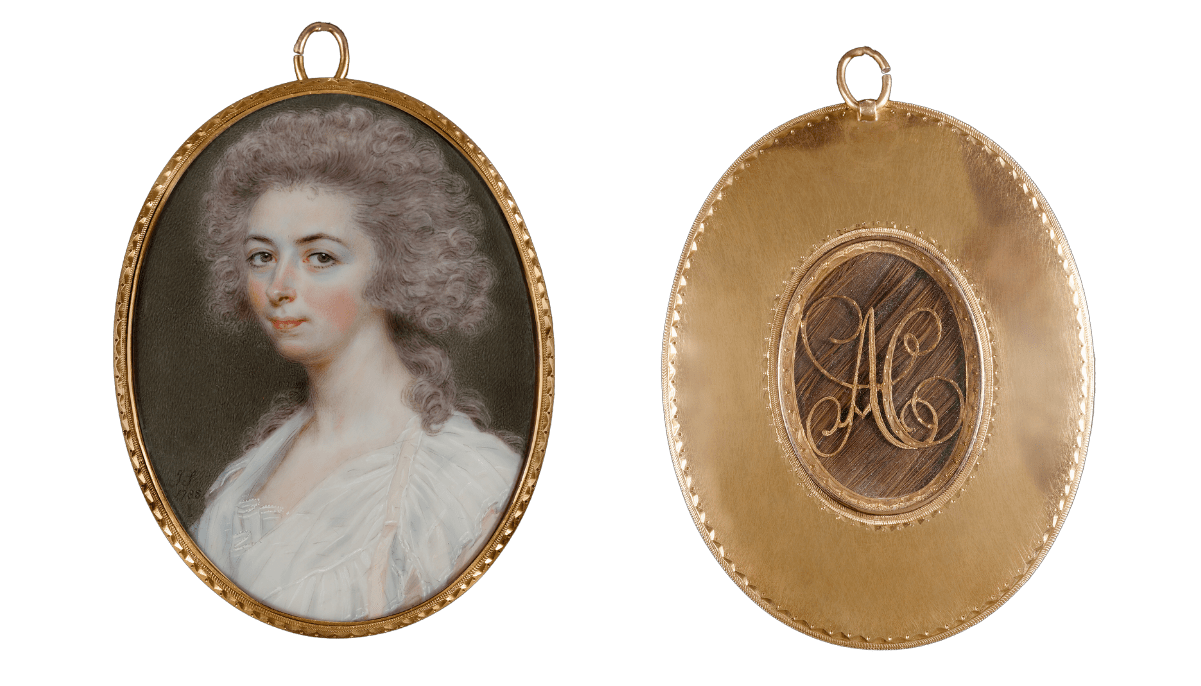

Chasing the Chases:

The process of identification of one of John Smart’s

‘Anglo-Indian’ miniatures

[1] FOSKETT, D., John Smart: The Man and His Miniatures, Cory, Adams & Mackay, London, 1964, p. 64.

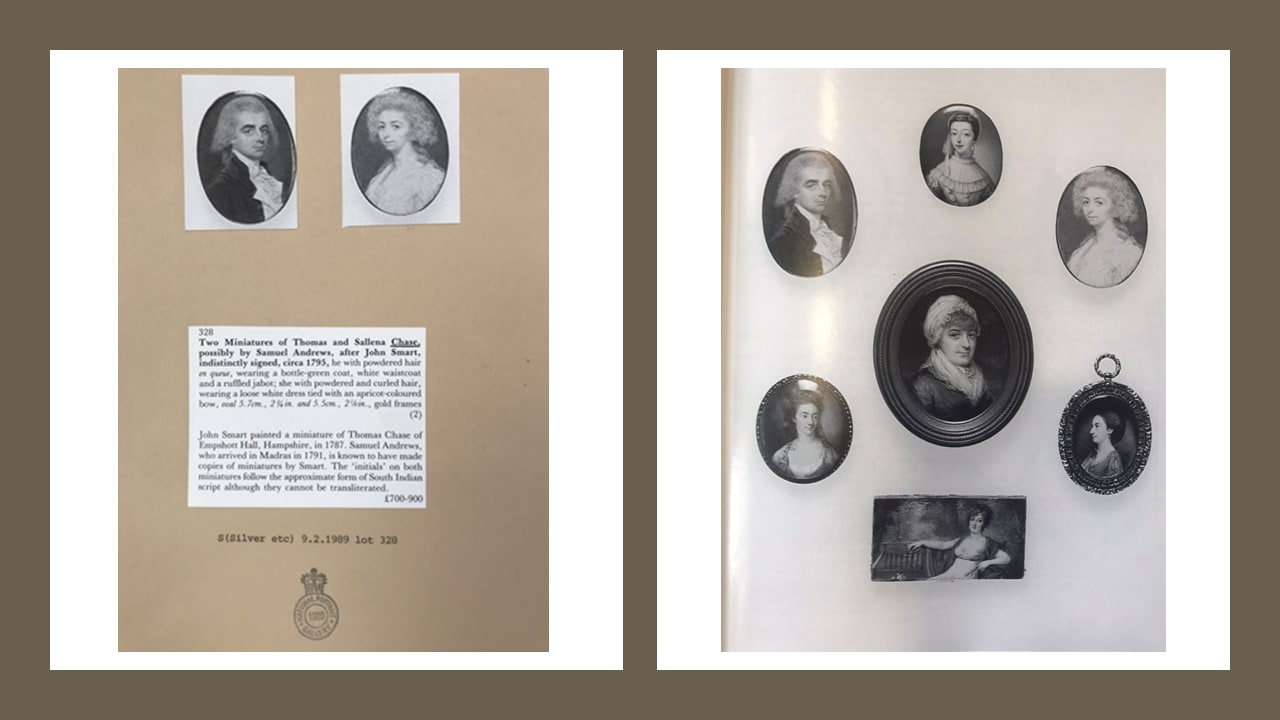

[2] Vestiges of Old Madras,III, p. 322.

[3] Heinz Archive, ‘Chase to Chatterj’ sitter box.

[4] Sotheby’s London, English and Continental Silver, Portrait Miniatures and Objects of Vertu, 9February 1989, lot 328.

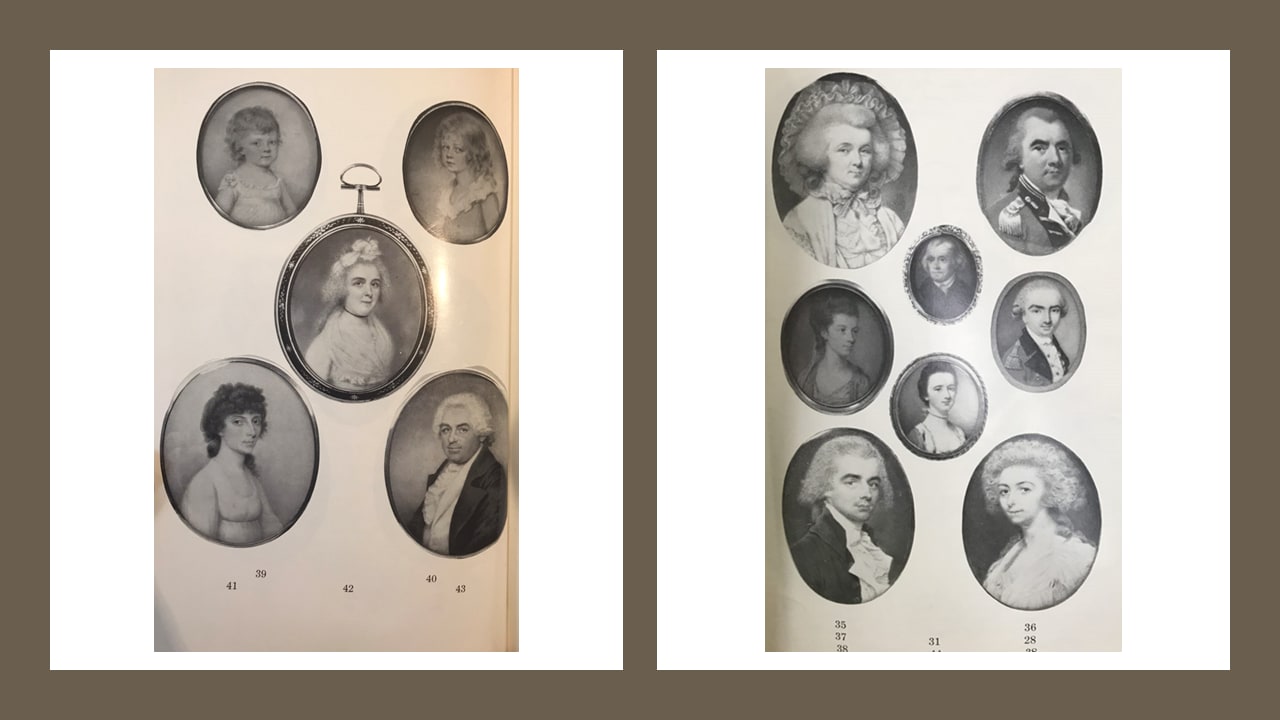

[5] Christie’s London, Catalogue of Miniatures, Gold Boxes and Objects of Vertu, 17 February 1970, lot 38, p. 12 (Corrigenda and Addenda).

[6] One sister was called Sarah and was painted by Smart in 1777. See Christie’s London, Catalogue of Miniatures, Gold Boxes and Objects of Vertu, 17 February 1970, lot 37 as ‘Miss Sarah Chase, later Mrs Tennant’.

[7] BL IOR 79 N/2/2/49, Madras Marriages, vol. C (1698-1948).

[8] See my Chase tree on Ancestry: https://www.ancestry.co.uk/family-tree/tree/193412958/family?cfpid=242517866727

[9] Bonham’s, Fine Portrait Miniatures, 24th June 2004, lot 129: https://www.bonhams.com/auctions/11052/lot/129/

[10] Christie’s London, Catalogue of Miniatures, Gold Boxes and Objects of Vertu, 17 February 1970, lot 40. See Miniatures at Kenwood: The Draper Gift, English Heritage, 1997, no. 46:

https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/richard-chase-charles-shirreff/6gG46Q61NnVipw

Richard George was not Richard Chase’s son, as stated incorrectly in https://www.bonhams.com/auctions/11052/lot/129/. For Richard George Chase’s birth and death certificates, see BL IOR 65 N/2/2/227 Madras Baptisms, vol. C (1698-1948), and Madras Burials in St Mary’s Cemetery 1749-1800, p. 25.

[11] Christie’s London, Catalogue of Miniatures, Gold Boxes and Objects of Vertu, 17 February 1970, lot 35. See ARONSON, J., and WISEMAN, M. E., Perfect Likeness. European and American Portrait Miniatures from the Cincinnati Art Museum, Yale University, 2006, p. 103.

[12] In the East India Company’s List of Civil Servants at the Fort St. George Establishment, Thomas Chase was first listed as a ‘Factor’, then as ‘Assistant to the Secretary - to the Select Committee’, later as a ‘junior merchant.’ See BL IOR A List of the Company’s Civil Servants, At Their Settlements in the East-Indies, 1785, p. 43; 1790, p. 38. From Merriam-Webster, a factor is ‘one that lends money to producers and dealers (as on the security of accounts receivable)’.

[13] In 1788, for instance, Thomas tried to establish a ‘Printing Office’ with the aim of producing a new, insightful newspaper for the British community. His plan was to include material in Persian and other Asian languages, such as ‘Dr Henry Harris’s Hindustani Dictionary’. However, this proposal was rejected by the Government as the newspaper would be in competition with the existing Madras-based licensed printer. The attempt to promote interest in and understanding of native culture and social systems also went against the Anglo-centric Cornwallis administrative system. See Vestiges of Old Madras, vol III, pp. 361-62.

[14] The firm changed its name to Chase, Parry & Co. when Thomas’s brother-in-law, ex-naval officer Henry Sewell, joined the partnership. By 1796 the firm had changed its name to Chase, Sewell, & Chase with the addition of Thomas’s brother, Richard Chase. In 1800, it became Chase, Sewell & Chinnery with the addition of John Chinnery, brother of the artist George Chinnery. After the death of Sewell in 1801, other partners joined Chase, Chinnery, and Macdouall and its power and influence grew. They owned at least four Madras-based merchant vessels: the Marquess of Wellesley, the Harrington, the Matilda, and the Gilwell. Thanks to these ships, they could buy cotton from Bengal, export spirits to Port Jackson, and take part in the salt and spice trades. See HODGSON, G.H., Thomas Parry Free Merchant Madras 1768-1824, Higginbothams, Madras, 1938, pp. 33, 38-39, and 46; CONNER, George Chinnery 1774-1852: Artist of India and the China Coast, p. 57; BL IOR/E/4/902, Despatches to Madras, p. 604; BL IOR/E/4/896, Despatches to Madras, p. 88.

[15] These were Mary Ann (b. 1789); Morgan Charles (b. 1790); Thomas Curtis (b. 1791); Laura Maria (b. 1792); Richard George (b. 1794); Rebecca (b. 1798). See BL IOR 65 N/2/2/57; IOR 65N/2/2/126; IOR 65 N/2/2/140; IOR 65 N/2/2/187; IOR 65 N/2/2/324, in Madras Baptisms, vol. C (1698-1948).

[16] Thomas’s sister, Miss Rebecca Chase (1763-1824), married Thomas’s partner, Henry Sewell, in 1790 (Vestiges of Old Madras,III, p. 420). Thomas’s brother, officer and merchant Richard Chase Jr (1754-1834), married Miss Elizabeth Neale in 1798 (BL IOR 79 N/2/2/323 Madras Marriages, vol. C). Sewell was a keen philanthropist who appears in various committees supporting the local Male Asylum, the Native Poor Fund, and the Native Hospital (The Madras Almanac for the Year of Our Lord 1800, p. 120). By 1793 Richard Chase and Sewell were also living on the same estate at Egmore, Madras. By the end of 1790s, they were both sitting as Aldermen for four months of the year and performing duties as Justices of the Peace during the rest of the year. In 1800 Richard Chase was appointed Mayor of Madras (Vestiges of Old Madras,III, pp. 420, 476-77, 554). Together with the wives of other prominent men, Mrs Chase and Mrs Sewell were both directresses of the Female Asylum (The Madras Register (1799), p. 145).

[17] The Madras Register (1799), p. 31.

[18] On 23rd January 1800, in the East-India Arrivals column, the Caledonian Mercury announced that “Mr and Mrs Chase and Family” were on the Walpole, bound for England.

[19] The Madras Almanac For The Year of Our Lord 1800, p. 64.

[20] Sometimes trade took Thomas further East. His name is recorded in the log of the Wexford, which sailed from Madras to China in September 1803 (http://www.heicshipslogs.co.uk./logs/h029.htm). At other times he was involved in selling Madeira wines or in the auction of oriental pearls (See Madras Courier, 11 August 1802; and25 June 1806).

[21] By 1803 Thomas was appointed ‘Senior Merchant’ and was running an insurance office called New Madras Insurance Company. Later he was working as ‘Paymaster’ at Vizag (on the coast between Madras and Bengal).

See An East-India Register and Directory, for 1803, vol. ii, pp. 130 and 211; British India Office Ecclesiastical Returns - Deaths & Burials N-2-3: https://search.findmypast.co.uk/record?id=BL%2FBIND%2F005137383%2F00551&parentid=BL%2FBIND%2FD%2F200608

[22] https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/20e41428-99d5-437d-8351-b0a07e2a85cd

[23] Madras Civil Servants, pp. 48-49.

[24] British Press, 25 April 1809.

[25] For instance, two of Ann’s daughters, Mary Ann and Laura Maria married in Bengal (respectively in 1810 and 1815), whilst her son, Richard George, applied for a post as ‘writer’ at Fort William. https://www.ancestry.co.uk/discoveryuicontent/view/109843:9901?ssrc=pt&tid=193412958&pid=242517874648; https://www.ancestry.co.uk/imageviewer/collections/61468/images/47593_83024005549_1487-00535?pId=450207; https://search.findmypast.co.uk/record?id=BL%2FBIND%2FJ-1-28%2F00024&parentid=BL%2FBIND%2F2334

[26] London Courier and Evening Gazette, 21 July 1837.

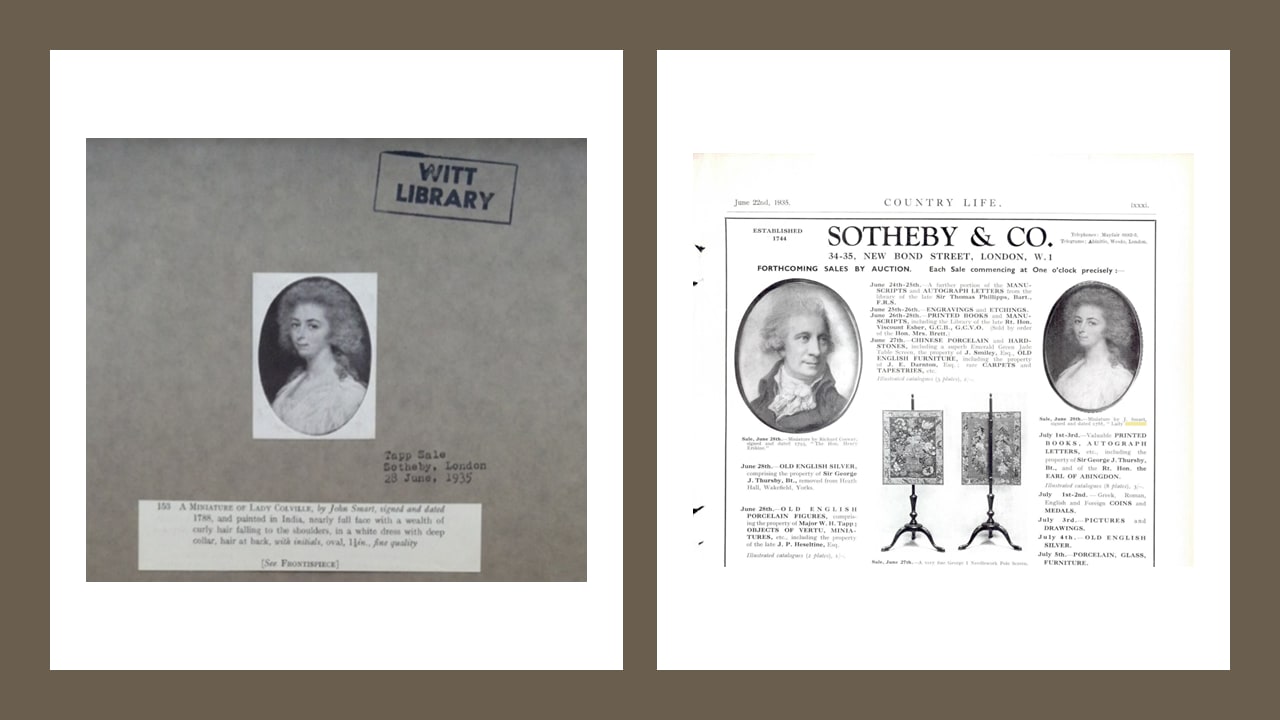

[27] Certificates for Covenanted Civil Servants in Writers' Petitions and Committee of College, J-1-28: https://search.findmypast.co.uk/record?id=BL%2FBIND%2FJ-1-28%2F00024&parentid=BL%2FBIND%2F2334

[28] https://www.ancestry.co.uk/family-tree/person/tree/193412958/person/242517879669/facts

[29] Eliza Rebecca Chase (1821-1901) was the daughter of Richard Chase, Thomas’s brother. Eliza R. lived with Rebecca in Beaumont Street for a period before getting married. Eliza R. first married the Rev. Edward Thomas Clarke and moved to Brighton. In 1871 she married John Elliott Bingham and moved to Tunbridge Wells.

[30] The London Gazette, 2 July 1901, p. 4432.

[31] It is possible the miniature was inherited by Thomas and Ann’s great-grandson, Alexander Edmund Coutts Trotter (1846-1913) of Milton Bridge, Midlothian. See https://www.ancestry.co.uk/family-tree/tree/193412958/family?cfpid=242517874648&fpid=242519292055

[32] SOTHEBY’S, Catalogue of Old English Porcelain Figures of the Bow, Chelsea, Bristol & Derby factories; Objects of Vertu, comprising […] Fine Signed Miniatures by John Smart, The Property of the Late J. R. Menzies, Esq., 28 June 1935, pp. 21-23.