The restoration of Michael Dahl's portraits of Rachel Russell, the Duchess of Devonshire, and Lady Mary Somerset, the Duchess of Ormonde [fig.1], currently on display at the Tate Britain, is a reminder of the complex history of marginalisation, erasure and invisibility which governs the representation of women throughout the history of art. Previously amputated due to the whims of a powerful earl, and now restored to their former full-length glory, they are representative of a call for a reconfiguration of the cultural portrayal of women.

Visual representations of women have been marginalised and vandalised for centuries, and the Gallery has witnessed three significant instances of such erasure, which are worth reflecting on. The vandalization of artworks depicting females is both socially and historically charged due to the treatment of, and rights available to, women throughout history.

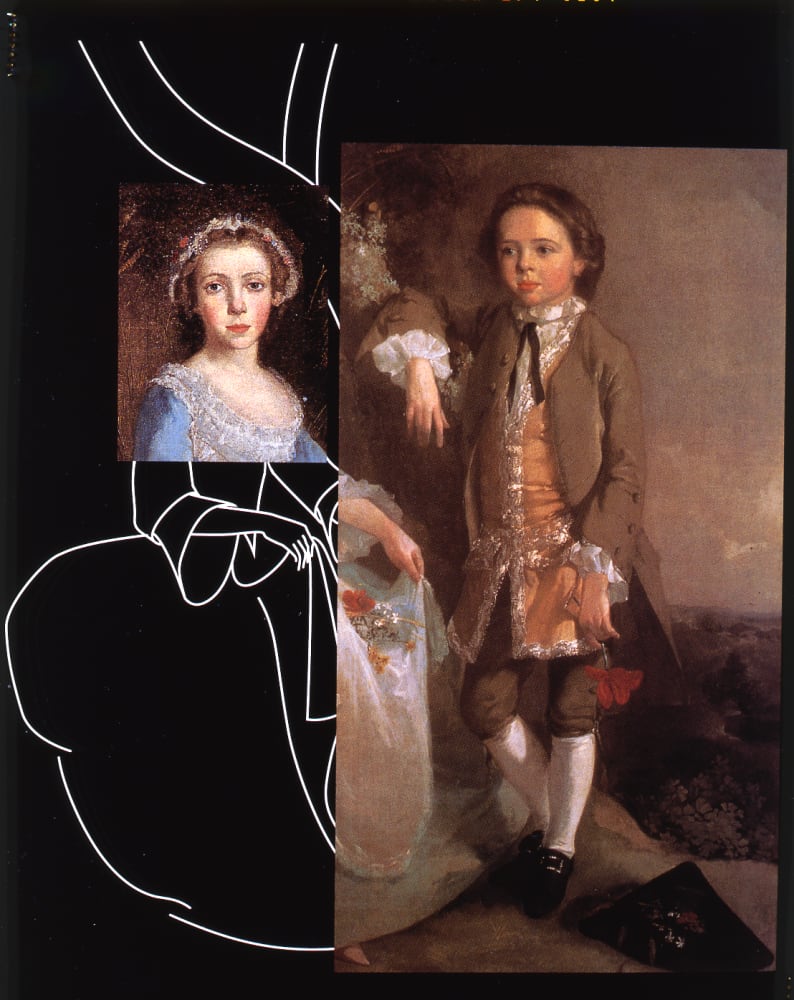

An example of such historical intervention is notable in a portrait of a brother and sister by the male artist Thomas Gainsborough [fig.2.]. In the present painting, a young boy is posed in a relaxed manner, adjacent to an ominous hand lifting, what is left of, an ornate dress. It is unclear why, or when, the separation of this composition occurred.

Yet, on the 10th April 1991, a portrait of the head of a young girl appeared at auction [fig.3]. Curiously attributed to male artist George Beare, the painting's composition and skilful brushstrokes undeniably leant themselves to the hand of Gainsborough. After an extensive period of research, a conclusion was reached; this miscatalogued portrait was, in fact, the lost head of the young girl in Gainsborough's painting. When placed next to the right-hand side of the painting, the continuity was unquestionable [fig.4]. The portrait was sold to Gainsborough's House, where the young woman has now been reunited with her brother. This reinstatement offers a positive vision for the restoration and conservation of future depictions of women throughout history.

Sadly, the location of the rest of the figure's body still unknown; the reduction and marginalisation of female representation is here manifest in the physical cutting, reducing and disregarding of a portrait of a young woman. However, whilst this ruthless act demonstrates a recurrent pattern in the historic treatment of portrayals of women, it is research and restoration that may enable a reflection on and reclamation of female autonomy.

Another instance of a similar act is presented in this fine portrait, also acquired through auction, which underwent restoration soon after its arrival to the gallery [fig.5]. Thorough cleaning restored the true colours of the original painting to their former glory, but, more importantly also unveiled a human leg on the left hand side of the canvas, previously concealed beneath layers of overpaint.

Feverish investigation commenced - surely this painting was, too, only part of a larger composition? A plausible case eventually built; the severed painting seemingly belonged to a 'self-portrait' by the artist Francis Hayman (1708-1776) [fig.6], held at the Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery, Exeter. This previously identified 'self-portrait' could now be discerned as a double portrait - a portrait of the artist and his first wife, from whom he separated shortly after he began work on the painting. At some point in its history, the painting had been cut down the middle and divided in two. Though we do not currently know enough about the history of this work to discern a concrete reason for this painting's division, we do know that this erasure and marginalization of women's stories, throughout history, is a painful and recurring trope.

It is surely a moment to celebrate, therefore, when such subversion of female representation is confronted. Thankfully, this painting has now been restored and the couple have been reunited, where they can be viewed at the Royal Albert Memorial Museum [fig 7]. Such restoration heeds scholar, bell hooks', plea for women's movement from 'object' to 'subject'.

The Gallery has been witness to further instances of erasure and omission of women's subjectivity, as can be seen, for instance, in this boldly modernist portrait by Duncan Grant. It depicts his close friend and physician Dr Marie Moralt, a central figure in the lives of Bloomsbury Group members Grant and Vanessa Bell (1879-1961) [fig 8].

Soon after Bell gave birth to her daughter Angelica (1918-2012), the child took a dramatic downturn in health and the local doctor administered medicine which worsened Angelica's condition, blaming Bell's milk. After consulting several doctors, Moralt installed herself at Charleston, where the couple lived, believing the doctor to be poisoning the child with carbolic. Discriminated against as a woman in the medical profession, Moralt had to fight to override the local doctor and eventually Angelica fully recovered. In a touching display of appreciation, Moralt was invited back to Charleston in May 1919 where she sat to both Grant and Bell who painted her simultaneously during the same sitting.

However, when acquired by the Gallery the portrait had inexplicably been folded over on its edges - disguising not only its signature, but major portions of the composition; most notably, the expressively clasped hands of the doctor herself [fig 9]. Given the aforementioned bias which Moralt experienced as a woman in a position of professional and intellectual authority, the act of eradicating her hands is one of brutal disregard.

Careful restoration now enables the portrait of Dr Marie Moralt to be viewed in full. The sitter's hands rest at the forefront of the painting, neither active nor passive, rather simply and purposefully waiting, charged with potentiality.

As Griselda Pollock put it, 'versions of the past ratify present order, producing 'a predisposed continuity''. It is through the research, restoration and inevitable rediscovery of female representation that we are able to disrupt 'a predisposed continuity' and reclaim an intersectional and complex understanding of individual feminine autonomy.

To read the full story of the Michael Dahl restoration, click here