Childhood in Miniature

Portrait miniatures were traditionally painted to mark the milestones in life – marriage, promotion and death being the major drivers for the commissioning of a small, portable portrait. From the 16th century, when portrait miniatures (then known as ‘limnings’) first emerged as a distinct type of portraiture, works featuring individual portraits of children were rare. Hans Holbein the younger (1497/8-1543), for example, only painted two portraits of children, Henry Brandon, second Duke of Suffolk (1535–51) and its companion piece of Charles Brandon, third Duke of Suffolk (1537/8–51) in the 1540s. The rarity of these images within Holbein’s oeuvre can be explained by the high-rank of the young boys, as the sons of Charles Brandon, first Duke of Suffolk, husband of Henry VIII’s sister Mary, they were educated alongside the future Edward VI. [Fig. 1/ 2] Despite acceding to the throne at the age of nine, portrait miniatures of the child-king Edward are extremely rare. This portrait miniature, attributed to the female court artist Levina Teerlinc (1510-1576) was likely painted circa 1550, possibly from life [fig.3].

Throughout the late 16th and early 17th century, children were treated as mini-adults in appearance and dress. It is very unusual to see children depicted in portrait miniatures of this period, and when they were, their age was often exaggerated through rich clothing and other attributes of adulthood – see for example Isaac Oliver’s portraits of two young girls aged four and five in the Victoria and Albert Museum [Fig 4]. In Peter Oliver’s circa 1620 portrait of a boy from the Egerton family, he captures however a natural openness and lack of self-awareness rarely seen in portraits of this date [Fig 5].

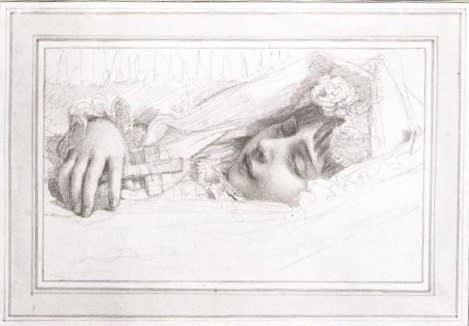

As the most personal of portrait types – often commissioned as secret objects, usually worn close to the body and only revealed at the choosing of the owner – portrait miniatures offer a portal into the ‘inner life’ of the past. The rarity of children portrayed in miniature was likely both an economic and emotional decision. Childhood is fleeting – children change by the day and become unrecognisable as years pass. They were usually still in the home – so there was little need to record the face seen on a daily basis. However, childhood mortality rates remained high from the 16th through the 19th centuries and occasionally portrait miniaturists were asked to record the terrible moment that ended childhood. An unusual sketch by the 18th century miniaturist Richard Cosway (1742-1811) of Triston Chambers was commissioned by his grief stricken parents as he lay struggling with whooping cough and eventually died aged only two years old [Fig. 6]. This must have been a particularly emotional commission for Cosway, whose own daughter had died of a fever and sore throat at the age of seven [Fig. 7].

Portraits of children can also belie the people they were to become in adulthood. The charming, almost saccharine portrait of Christiana Cranstoun Tugwell by George Engleheart (1750-1829) shows no hint of the tragedy to come, when she would, in January 1839, murder her twin boys and take her own life through Prussic acid poisoning [Fig. 8]. Likewise, the carefree child shown in Henry Spicer’s portrait enamel of Louisa Holroyd at the age of six, does not embody the teenage Louisa, who was thrown out of the family home by her father, the 1st Earl of Sheffield, due to her unstable physical and mental health [Fig. 9]. A glimpse into the interests and education of one of the most powerful families in Europe can be found in the portrait miniature of the Archduke Charles Joseph of Austria, as he studies a book showing the illustration of a rare rhinoceros, possibly ‘Clara’, who toured Europe in the 1740s. [Fig. 10]. As with all royal portraiture there is sense of propaganda here; the child shown being far too young to read the book on his lap. Archduke Charles Joseph, brother of the doomed future French queen, Marie Antoinette, was to die in his teens of smallpox, much to the distress of his mother the Empress Marie Theresa.

As with other types of portrait miniature, these small images give a glimpse of the private lives of the past. Often poignant, sometimes surprisingly unsentimental, miniatures of children reflect the emotional mind-set of the past more than any other type of portrait. Although rare in this oeuvre, child portraits are key to a deeper understanding of past attitudes to childhood.