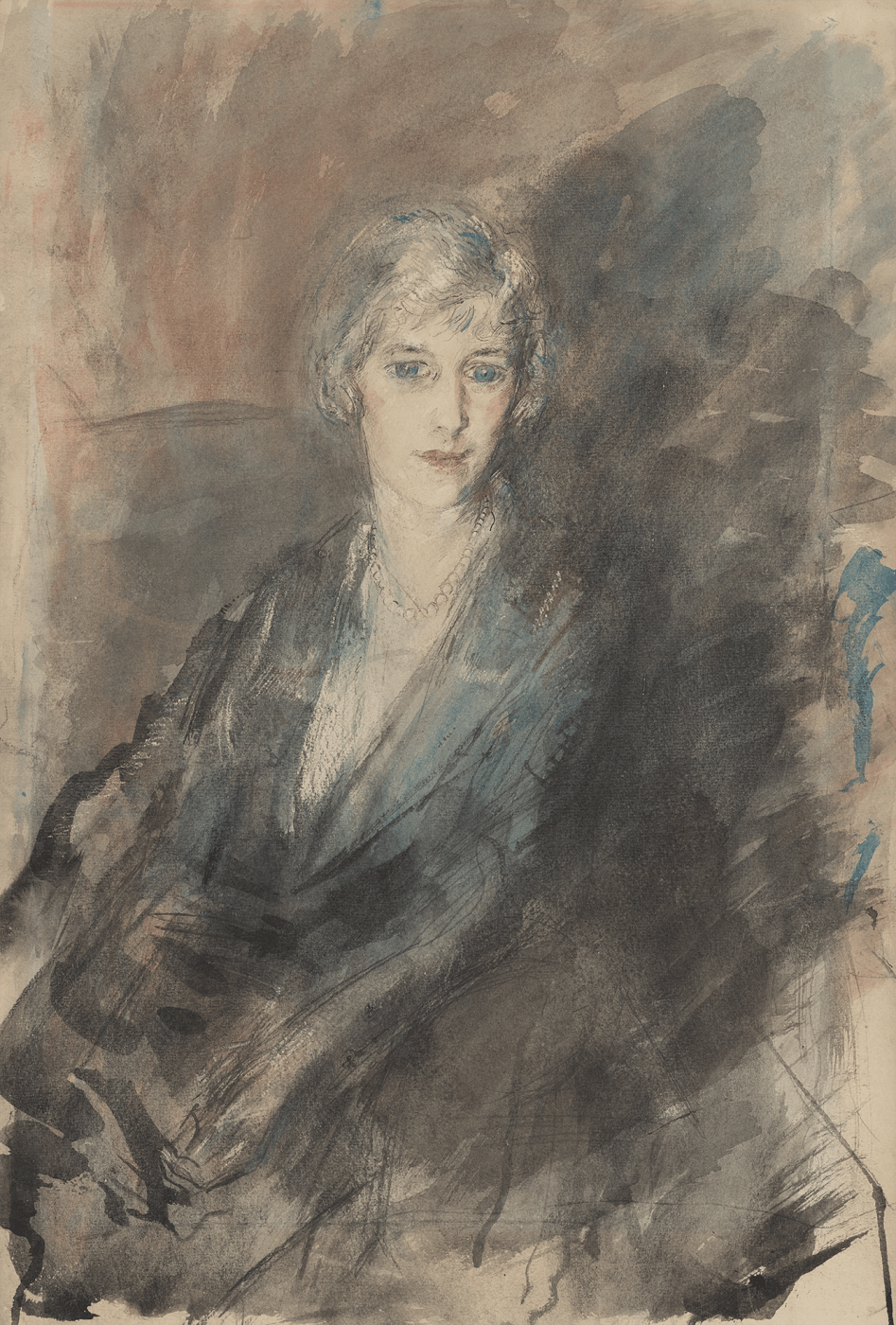

This captivating portrait of Katherine Duer Mackay (1878-1930) was presumably completed during one of Ambrose McEvoy's trips to America. His famed depictions of human character and beauty, particularly of women, became sought after and he maintained an illustrious list of clients spread between the United Kingdom and America, where he was represented for a period by the most celebrated international art dealer of the day, Lord Duveen.[1]

Born in New York City in 1878, Katherine Duer Mackay became an esteemed figure in the quest for women's suffrage. Mackay was an only child and direct descendant of the socially prestigious Lady Kitty Duer, daughter of Lord Stirling. In 1898, she married Clarence H. Mackay, heir to a New Money fortune of silver mining and cable technology, who would later become chairman of the Postal Telegraph-Cable Company.

Mackay's first political undertaking occurred in 1905 when she was elected to the Roslyn Board of Education. The presence of women in any form of politics at this time was rare, to the extent that Mackay showed noteworthy political acumen when she stated her need to 'force my way upon the school board in my own village'.[2] Garnering a spirit of reform, Mackay contributed to educational initiatives which sought to end to corporal punishment. This gained her immense popularity amongst the students, who reportedly took to the streets in celebration and wrote the words 'Mrs. Mackay is All Right' on the fences, pavements and house doors of the village.[3]

In 1908, Mackay became one of the first social figures to endorse women's suffrage in the early 20th century when she became the founder and president of the Equal Franchise Society (EFS);

'…I uphold the principle involved in giving women a vote in national affairs as well as in local municipal ones. Their power for good is unquestioned, and that there may be bad woman voters is as old as the contention that there are bad men who have the right to cast the ballot.'[4]

Mackay lobbied against the damaging contemporary stereotype of 'frumpy' or 'masculine' images of suffragettes, often circulated in contemporary popular press, whose activism was commonly considered unladylike by the upper-class. Surrounded by wealth, upper-class circles and social prestige, Mackay recognised her privileged social position and used it to gain support for the movement. Her popularity and influence saw her frequent appearance in the press which Mackay used to advance awareness and support of women's suffrage. Johanna Neuman, author of Gilded Suffragists: The New York Socialites Who Fought for Women's Right to Vote, writes; 'Mackay understood that reporters who came to 'cover her clothes' could also be enticed to take a statement on suffrage'.[5]

Mackay's influence is evidenced further through her attendance at an Interurban Suffrage Council lecture at Carnegie Hall (December 1908), which sold out of seats upon the accountment of Mackay's attendance. Her reputation and correspondingly lavish tastes were extended to the EFS's immaculately decorated offices at Madison Square, which were rented for the group's meetings.

Quick witted and intelligent, Mackay was not without her antagonists. Referring to her sometimes hostile neighbours, Mackay stated; 'Even opposition is better than indifference … Of course, those who think differently discuss their views and that leads to enlightenment on both sides of the question.'[6]

By 1911, Mackay had resigned as EFS president, but remained a member. The same year, rumours were circulated of a possible affair between Mackay and her husband's doctor, Dr. Blake. By 1914 Mackay and her husband were divorced and full custody of their three children was given to Clarence Mackay. In November 1914, Mackay married Dr. Blake and the two continue to fight for women's suffrage in Paris before returning to New York amongst the anxiety of the First World War. Upon returning to New York, Mackay and Dr. Blake divorced and Mackay tragically died of cancer in 1930.

Ambrose McEvoy captures Mackay's powerful influence and legacy which inspired a generation of women, whose efforts would ultimately attain the vote for women.

[1] Akers-Douglas, (ed.) Hendra, Divine People, p.176.

[2] K. Duer Mackay quoted in M. B. Downing, 'Mrs. Clarence Mackay, Wife of a Millionaire, Works for Woman's Suffrage.', The Sunday Star, 25 October 1908 [Accessed on 18.11.2020: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1908-10-25/ed-1/seq-47/].

[3] "Mrs. Mackay Is All Right" The New York Times, 16 August 1906 [Accessed on 18.11.2020: https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1906/08/16/101845368.pdf].

[4] K. Duer Mackay quoted in M. B. Downing, 'Mrs. Clarence Mackay, Wife of a Millionaire, Works for Woman's Suffrage.', The Sunday Star, 25 October 1908 [Accessed on 18.11.2020: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1908-10-25/ed-1/seq-47/].

[5] J. Neuman, Gilded Suffragists: The New York Socialites Who Fought for Women's Right to Vote (New York: NYU Press, 2019).

[6] K. Duer Mackay quoted in M. B. Downing, 'Mrs. Clarence Mackay, Wife of a Millionaire, Works for Woman's Suffrage.', The Sunday Star, 25 October 1908 [Accessed on 18.11.2020: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1908-10-25/ed-1/seq-47/].