Miniatures from the Bearsted Collection

An intimate exhibition of eight Elizabethan and Jacobean portrait miniatures

19 November—19 December 2025

Miniatures from the Bearsted Collection

Portrait miniatures on display

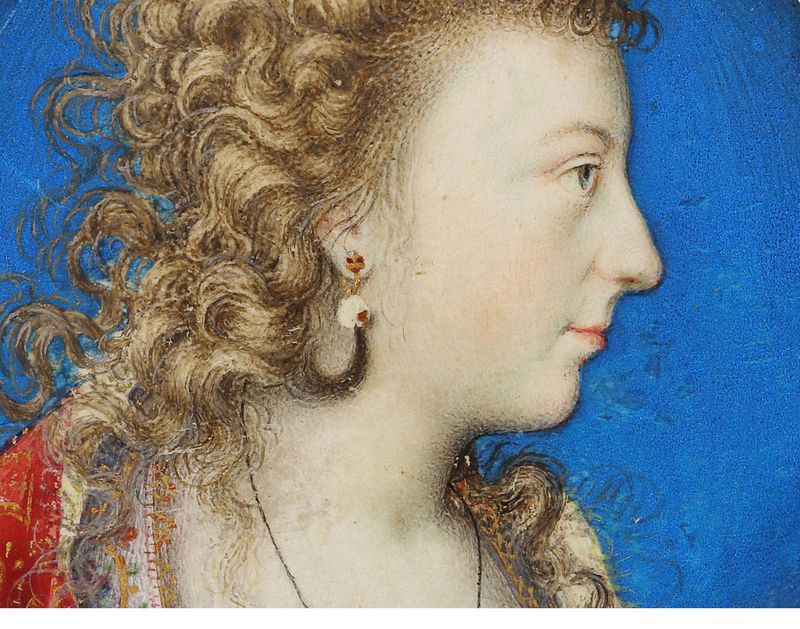

Nicholas Hilliard (1547-1619)

A lady, traditionally identified as Elizabeth (1588-1633), née Stanley, Countess of Huntingdon, c.1603-1615

Going at least as far back as the eighteenth century, when Sir Horace Walpole owned this miniature, it has been identified as a portrait of Lady Elizabeth Stanley (1587–1633), third and youngest daughter of Ferdinando Stanley, 5th Earl of Derby, and his wife, Alice, née Spencer. Via her father, Elizabeth was – like her elder sisters, Anne and Frances – a direct descendant of Henry VII and, thus, in her youth a potential successor to the ageing and childless Queen. On 15 January 1601, Elizabeth married Henry Hastings, who became 5th Earl of Huntingdon on the death of his grandfather in 1604. No certain image of the young Elizabeth is known to survive for purposes of comparison with this miniature. But an engraved portrait of the mature Elizabeth by John Payne printed in 1635 (two years after her death) as the frontispiece to ‘A Sermon Preached at Ashby-de-la-Zouche’ depicts a woman with a similarly prominent nose, broad forehead, wide-set eyes and high, recessed hairline.

Hilliard’s sitter is portrayed with long, flowing hair: an indication either that she was unmarried at the time this likeness was created or, if married, that she has been portrayed in masquing attire. The latter seems the more likely scenario, particularly if the traditional identification of the sitter is accepted: Elizabeth Stanley was married at the age of about fourteen and the lady portrayed here looks to be slightly older, perhaps in her late teens. The sitter’s headwear, like her loose hair, is also evocative of the world of the late Elizabethan and early Jacobean court entertainment. What Hilliard has depicted here is probably either an ‘attire’ or a ‘circlet’, examples of which are recorded in the inventories of Anne of Denmark, the greatest patron of the early Stuart court masque.

Elizabeth – like her mother and both of her sisters – was an enthusiastic patron of the masque and other forms of courtly drama. In 1603, ‘Ladie Hastings’ (as Elizabeth then was) accompanied Anne of Denmark on her progress south from Edinburgh to London for her coronation as Queen of England, pausing en route to partake of numerous masques and other entertainments laid on within the confines of aristocratic residences, including Althorp, in Northamptonshire, where Elizabeth’s mother, Alice (née Spenser), mounted a spectacular series of festivities, including a newly commissioned masque by Ben Jonson. In 1607, Elizabeth commissioned John Marston to devise an elaborate masque for performance at her marital home, Castle Ashby, in Northamptonshire, for which Marston represented her as Selas, ‘the grace of the Muses’. Elizabeth was also one of several aristocratic ladies who, alongside Queen Anne, performed in Jonson’s Masque of Queens at Whitehall Palace in 1609. Presumably, too, masques or other dramatic entertainments were amongst the festivities laid on for James I when he visited Castle Ashby during the summer progresses of 1605 and 1612.

Find out more

Isaac Oliver (c. 1565-1617)

A young lady wearing a masculine-style black and orange doublet and black hat (with hat jewel) and an orange sash, c.1600-1615

This exceptionally vibrant miniature is in extraordinarily good condition. Its colours – most notably, its brilliant oranges, which ‘pop’ against Oliver’s solid blue background and against the black elements of the sitter’s dress – are virtually unfaded and undimmed with the passage of time.

The identity of the sitter, who has chosen to be portrayed in an androgynous fashion, is unknown. But her attire and general self-presentation are suggestive of a spirited, perhaps slightly rebellious nature. Flowing tresses worn down rather than up were a sign that a lady was unmarried (or in masquing costume). Yet the ‘love lock’, in which one section of hair was left to grow longer than the rest so that it could be brought forward – as depicted in this miniature – was predominantly a male fashion. In short, Oliver’s sitter seems to be the sort of young lady the anonymous author of the 1620 pamphlet Hic Mulier (‘The Man-Woman’) had in mind when railing against the ‘insolencie of our women, and theyre wearing of brode brimd hats [and] pointed dublets’.

Certainly, the broad-brimmed hat and pointed doublet worn by this sitter are masculine in style. As is clear from both written and visual evidence, ladies at the late Elizabethan and early Jacobean courts often donned such attire for hunting, as may be seen in Paul van Somer’s life-sized oil painting of Anne of Denmark with her horse and hounds (1617), now in the Royal Collection. Sometimes, too, ladies wore such garb when ‘in character’ for a court masque or other entertainment. For example, the text of Ben Jonson’s Masque of Queens – performed at Whitehall Palace in 1609 by Queen Anne and eleven noblewomen – indicates that Hypsicratea, Queen of Pontus made her entrance wearing ‘a masculine habit’.