English School

King James VI & I (1566-1625)Provenance

Possibly Robert Sparrowe, (1571-1614), portman of Ipswich;

Thence by family descent (label on reverse).

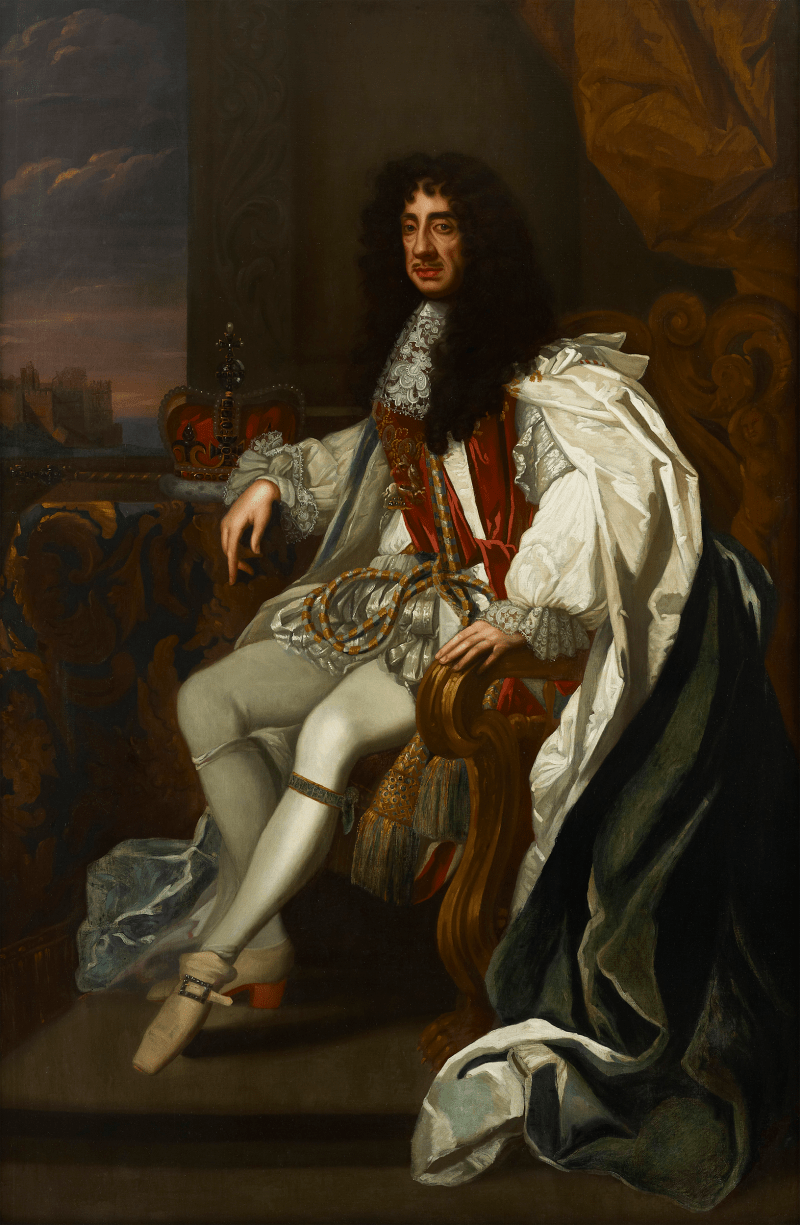

This strikingly imperial and propagandist portrait of King James VI & I was painted not long after he acceded to the English throne and is unique within his documented iconography in oil paint. Its visual elements, outlined below, reveal a ruler’s message of union and peace which would not have been lost on an initiated contemporary audience.

The task of identifying the source of influence for the present portrait is not straightforward. That the artist of the present work was English not Scottish is evident from the coat of arms, which can be identified as the type used in England at this date – there was a variant of this design favoured in Scotland which gave greater prominence to the red lion rampant.

The positioning of James’s body, turned slightly away from the viewer with a cloak over his shoulders, is reminiscent of De Critz’s depiction from c.1604, a fine version of which is in the Scottish National...

This strikingly imperial and propagandist portrait of King James VI & I was painted not long after he acceded to the English throne and is unique within his documented iconography in oil paint. Its visual elements, outlined below, reveal a ruler’s message of union and peace which would not have been lost on an initiated contemporary audience.

The task of identifying the source of influence for the present portrait is not straightforward. That the artist of the present work was English not Scottish is evident from the coat of arms, which can be identified as the type used in England at this date – there was a variant of this design favoured in Scotland which gave greater prominence to the red lion rampant.

The positioning of James’s body, turned slightly away from the viewer with a cloak over his shoulders, is reminiscent of De Critz’s depiction from c.1604, a fine version of which is in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. In the present work, however, the artist has replaced the Garter chain with the Lesser George on a Garter ribbon, which is more reminiscent of the early Hilliard miniatures of James (Fig.1). It is also clear that the artist of this portrait was very familiar with English monarchical iconography in printed form, which tended to be more elaborate and would often include mottoes, Latin inscriptions and royal symbolic devices such as the items of regalia we see here. Although these items do appear in painted portraits of James as king, they are seldom seen before 1618 when Paul van Somer produced his new likeness of James.

When Elizabeth I died on 24 March 1603 James, already King of Scotland, was pronounced King of England and Ireland. Although his succession was met with little resistance, the atmosphere was tense as Parliament awaited his arrival. An outbreak of the plague, however, kept James away from London for some time following his coronation, and it wasn’t until March 1604, one year after his accession, that James gave his first speech to Parliament.

The speech was revealing on several levels, not least as it reinforced his belief in the divine right of kings and the monarchy’s supremacy. By referring to England and Scotland collectively as Great Britain, he also made clear his ambitions to create a political union, using geographical references to reinforce the idea: ‘what God hath conjoined, then let no man separate’[1] and biblical references to reflect his authority over the two countries; ‘I am the Shepherd, and it is my flock.’[2]

Later, on 20 October 1604, this desire for union was boldly reinforced by a royal proclamation in which James claimed the name and style ‘King of Great Brittaine, France and Ireland’, and demanded it is used ‘upon our currant Moneys and Coynes of Gold and Silver hereafter to be Minted’.[3] A new coinage was therefore introduced, on which the separately inscribed words ‘ANG’ and ‘SCO’ (England and Scotland) were replaced with ‘BRI’ or ‘BRIT’ (Britain). The inscription in the top left corner of the present work reads: ‘IACOBUS. D.G./MAG.BRI.FRAN./ E.T.HIB.REX’ (‘James by the Grace of God King of Great Britain France and Ireland’), which suggests the portrait was painted after the proclamation was issued on 20 October 1604.

The coat of arms seen in the top right corner of the portrait was introduced by James not long after his accession and combined the arms of Scotland with those of England, Ireland, and France. The intertwined red and white roses of Lancaster and York, which join above the crown and form a Tudor or ‘Union’ rose with ‘I R’ (‘Jacobus Rex’) on either side, legitimises James’s claim to the throne as the great-grandson of Margaret Tudor, daughter of Henry VII.

Peace with Spain was deemed a priority by James on his accession and was achieved several months later when delegates of Spain and England signed the Treaty of London at Somerset House. The war, which had been ongoing since the later stages of Elizabeth I’s reign, had become an increasing drain on the country’s finances, and peace would bring, amongst other benefits, lucrative trade agreements. As well as financial benefits, the peace agreement also required Spain to acknowledge England as a Protestant nation, much to the disdain of English Catholics. Religious clarity was essential to the union but this was no simple task, and the following year on 5 November 1605 a plot to assassinate James by laying explosives under the House of Lords was foiled. The Gunpowder Plot, as it became known, was conceived by several dissatisfied English Catholics, one of whom, Guy Fawkes, had fought on the side of the Spanish during the Eighty-Years War and had already tried to gather support in Spain for a Catholic rebellion in England.

Unified faith with James as supreme principal is symbolised by the orb on which his left-hand rests. An orb surmounted by a cross is familiar royal regalia (along with the sceptre held in his right hand) and symbolises Christ as sovereign of the world. With James’s hand placed conspicuously on top of the orb and around the cross, there is a clear suggestion of godly rule, a predictable message from a monarch who believed so deeply in the divine right of kings. Within the orb, there is depicted a stormy seascape with small vessels flanked on either side by large waves or rocks. A rock in the foreground is dangerously close to a passing ship, and the flames at its base may warn of further impending danger. This imagery is most likely an extension of the strong message of unity seen elsewhere in the painting; divided lands and troubled waters are all themes to which James relates in his 1604 speech to Parliament.[4] Above this scene of drama, however, is a bright sky with sunlight bursting through clouds – symbolic, perhaps, of divine light, reflecting James’s unifying protective presence over his earthly subjects.

It is perhaps surprising, given James’s need for loyalty and support at the outset of his reign, that his iconography is so sparse, not least as he would have witnessed how successfully Elizabeth I used her imagery as a tool for gaining and maintaining political support in the later years of her reign. For the most part, James’s portraits from the early years of his rule derive from a single head pattern by John de Critz the Elder (d.1642), painted c.1604. This head pattern was then used to reproduce further portraits of varying sizes and remained in circulation until Paul van Somer (1577/8 – 1621/2) was commissioned to paint a more up-to-date likeness in 1618. We also know that from the outset of his reign that James was patronising the eminent miniaturist Nicholas Hilliard.

[1] Anon. (1616) The Workes of the Most High and Mighty Prince, James. London: Robert Barker and John Bill, p.488.

[2] Ibid.

[3] 20 October 1604. Larkin, J.F & Hughes, P.L (eds.), (1973) ‘Proclamation concerning the Kings Majesties Stile, of King of Great Britaine &c. Westminster’, Royal Stuart Proclamations, New York: Oxford University Press.

[4] Ibid, pp. 488-489.