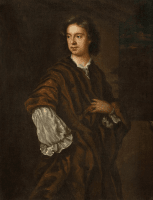

Mary Beale's portraits of her husband Charles powerfully reflect their collaborative partnership and defiance of gender conventions. This spirited, small-scale portrait of Charles was painted as a companion piece to Beale’s Self Portrait Holding an Artist's Palette.

Depicted in three-quarter-length contrapposto and glancing away from the viewer, this work is steeped in Baroque panache and shows the strong influence of Sir Peter Lely. The composition was used by Lely in his portrait of Henry Brouncker, 3rd Viscount Brouncker (1624/5-1688), which, given the compositional similarities, suggests that Beale may have seen it, perhaps in Lely’s studio or possibly through their social connections with the Royal Society: Henry was the younger brother of William Brouncker, 2nd Viscount Brouncker, the first President of the Royal Society.

Both companion portraits are early examples of Beale’s ‘in little’ works, which transfer all the compositional complexity of a full-sized portrait on to an intimate and detailed scale. When displayed side by side, Charles's portrait gazes indicatively...

Mary Beale's portraits of her husband Charles powerfully reflect their collaborative partnership and defiance of gender conventions. This spirited, small-scale portrait of Charles was painted as a companion piece to Beale’s Self Portrait Holding an Artist's Palette.

Depicted in three-quarter-length contrapposto and glancing away from the viewer, this work is steeped in Baroque panache and shows the strong influence of Sir Peter Lely. The composition was used by Lely in his portrait of Henry Brouncker, 3rd Viscount Brouncker (1624/5-1688), which, given the compositional similarities, suggests that Beale may have seen it, perhaps in Lely’s studio or possibly through their social connections with the Royal Society: Henry was the younger brother of William Brouncker, 2nd Viscount Brouncker, the first President of the Royal Society.

Both companion portraits are early examples of Beale’s ‘in little’ works, which transfer all the compositional complexity of a full-sized portrait on to an intimate and detailed scale. When displayed side by side, Charles's portrait gazes indicatively towards his wife, who holds her artist’s palette and maulstick and faces the viewer. This compositional device is also apparent in Beale’s earlier self-portrait with her husband and son, in which Charles’s attention is again fixed on his wife, who alone faces the viewer.

Just as Beale transcended gender norms to thrive as an artist, so too did Charles defy traditional notions of masculinity by actively supporting her artistic career. Their collaborative relationship, both in marriage and business, challenged the prevailing view that husbands should be the sole providers for their families – a dynamic reinforced by the double compositions in which Charles ‘looks on’ at Mary, the family figurehead proudly brandishing the tools of her profession.