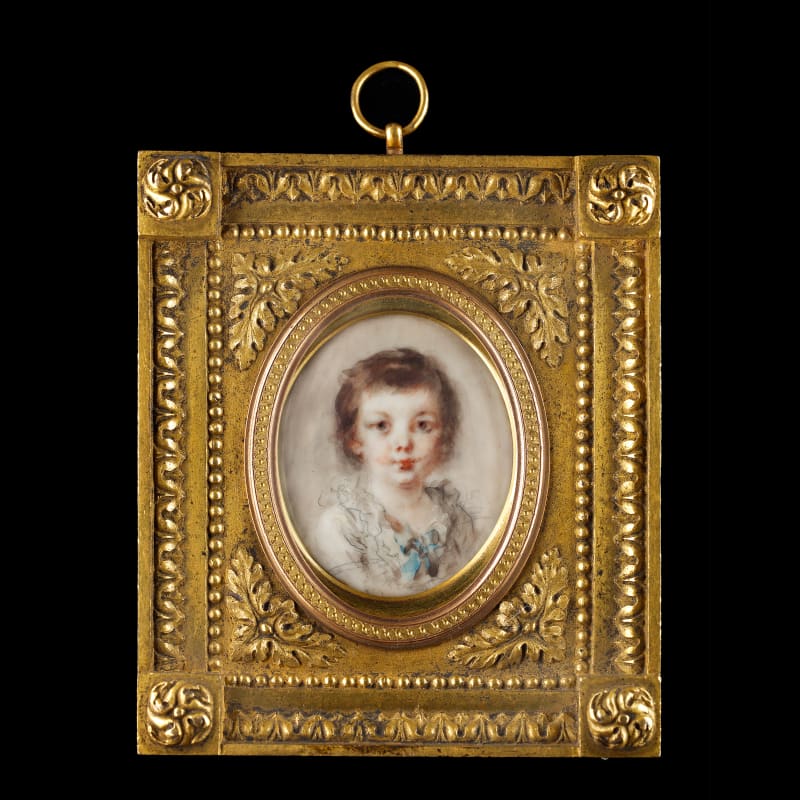

This extraordinary portrait miniature of Commodore Johnstone, the one-time Governor of West Florida, is one of three known versions. Described as Bogle’s ‘masterpiece’, this miniature is likely the source for Henry Raeburn’s portrait of Johnstone in a rare occurrence of an oil painter working from a miniature.[1] Raeburn painted Johnstone’s wife, Charlotte (nèe Dee) in mourning for her husband in 1791, where she holds a portrait miniature which may be the present work, or the version in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery.[2]

The current version of this portrait is the only version signed by the artist on the right hand side, the other two being signed on the left.[3] The portrait can be dated to circa 1785, a few years after his marriage on the return voyage from his second trip to America in 1782. Bogle, a fellow Scot, was the son of a Scottish excise officer. Described by a contemporary as ‘a little lame man, very proud, very poor...

This extraordinary portrait miniature of Commodore Johnstone, the one-time Governor of West Florida, is one of three known versions. Described as Bogle’s ‘masterpiece’, this miniature is likely the source for Henry Raeburn’s portrait of Johnstone in a rare occurrence of an oil painter working from a miniature.[1] Raeburn painted Johnstone’s wife, Charlotte (nèe Dee) in mourning for her husband in 1791, where she holds a portrait miniature which may be the present work, or the version in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery.[2]

The current version of this portrait is the only version signed by the artist on the right hand side, the other two being signed on the left.[3] The portrait can be dated to circa 1785, a few years after his marriage on the return voyage from his second trip to America in 1782. Bogle, a fellow Scot, was the son of a Scottish excise officer. Described by a contemporary as ‘a little lame man, very proud, very poor and very singular', Bogle excelled in painting on a larger scale with compositions that were unusually ambitious for a miniature painter of the 1780s. The closest image to the present work would be the ‘Portrait of the Dutch Governor of Trincomalee’ in the Victoria and Albert Museum dated 1780 [P.83-1910]. This is most likely a portrait of Iman Willem Falck (1736-1785), who was the Dutch colonial governor who served as the 32nd Governor of Zeylan (Ceylon) during the Dutch period in Ceylon.[4]

George Johnstone led an extraordinary life and was himself of notable character (although not universally liked or admired). He was the fourth of the seven sons of Sir James Johnstone of Westerhall, third baronet (1697–1772), and his wife, Barbara Murray (d. 1773), daughter of the fourth Lord Elibank. Governor of Western Florida from 1763, a member of Parliament from 1768, and one of the commissioners appointed to negotiate with the American Colonies in 1778, Johnstone was variously described by contemporaries as courageous, disrespectful and ambitious. His career in the navy and politics continually lurched between failure and success – but here Bogle has painted him towards the end of his life, relaxed and contemplative.

Johnstone’s friendships often led to interesting opportunities – including his close alliance with the dramatist John Home. As secretary to John Stuart, third earl of Bute, appointed by George III as prime minister, Home was able to manoeuvre Johnstone to the post of governor of the new British colony of West Florida in 1763. Bute was also swayed by the fact that Johnstone was a fellow Scot – an aspect that aroused much criticism in the press. Johnstone, however, was encouraged by the prospect of a personal fortune, as the province's location on both the Gulf of Mexico and the Mississippi River promised a profitable future for West Florida, which he envisaged as 'The Emporium of the New World'.[5] Johnstone’s time in West Florida could be described as mixed at best. After an initial success negotiating with the indigenous population, within two years he was resolute in wanting war with the Creek Indians. This stance was at odds with the British Government who at this time strove for peace in North America. In 1767 he was unceremoniously removed from the post, but was proud to be referred to as ‘Governor Johnstone’ for the remainder of his life.

Turning his interest back home in England to the East India Company and politics, capitalising on his reputation as a man of business and an orator, he joined the Commons as the member for Appleby ‘where his total want of fear and his adroitness with a pistol made him a useful addition to his party.’. Once in Parliament, he again turned his attention to America, where he largely backed Rockingham against North. Here is spoke out against the slave trade, describing it as 'a commerce of the most barbarous and cruel kind that ever disgraced the transactions of any civilised people'.[6]

After 19 years ashore, and another year in America, Johnstone was back on board ship wanting to support his country against the French and Spanish. He took his flagship, the Romney, to join the Channel Fleet of Sir Charles Hardy, whose task was to thwart the enemy fleets. In 1780, he was given command of a small expedition against the Cape of Good Hope, Here, he personally attached a boat to a burning East-Indiaman and then had it towed to a lee shore shortly before it exploded. The consequence was his capture of five intact Dutch ships and a good deal of prize money. Now aged fifty-two, he stopped in Lisbon to marry Charlotte Dee, the daughter of the British Vice-consul. With Hodgkin’s disease now claiming his health and vigour, he re-entered Parliament and obtained a directorship at the East India Company. In 1787 he succumbed to Hodgkin’s disease at his home in Bristol.[7]

The unusual atmosphere of this portrait rests on many factors. Although often intimate, portraits of the later eighteenth century rarely offer such an insight into the unguarded life of such a prominent figure. Not looking at the viewer, it is as though Johnstone is unaware of the presence of the artist. His crumpled waistcoat and lack of wig alludes to an ‘off-duty’ moment, despite his choice of dress being his naval uniform. Johnstone’s unusual hand gesture may simply be an attempt on Bogle’s part to bring a naturalistic element to the portrait, or it may have some hidden meaning. Sign language has been suggested by some scholars, but there is no evidence that either Johnstone or his wife were deaf. The portrait is an unusually frank depiction of a man known to be tempestuous and recondite in nature, and alludes to a trust, even a friendship, between artist and sitter.

[1] A version of this portrait is in the Royal Museums, Greenwich BHC2808.

[2] The portrait of Charlotte Johnstone was sold Sotheby’s, New York, 28th January 2005, with the later 19th century provenance of Mrs Edward Ferguson. The portrait of George Johnstone attributed to Raeburn also had the same provenance when exhibited at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in 1884 (Col. Major S. F. M. Ferguson). The archive boxes at the National Portrait Gallery show that a further copy by George Hayter after Raeburn was in the possession of the family in the later 19th century.

[3] One version of the miniature is in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, purchased in 1982 for £21,600. This portrait had been in the collection of John Pierpont Morgan. The other version, also signed on the left, was sold at Christie’s London in 1986 (£9,720).

[4] Another portrait known in an engraving in the National Galleries of Scotland of James Byres of Tonley, 1734 – 1817, Architect and antiquary, is similar in composition and shows the sitter reading a book in a panelled room.

[5] Georgia Gazette, 10 Jan 1765.

[6] W. Cobbett & J. Wright (eds.), The Parliamentary History Of England, From The Earliest Period To The Year 1803: From Which Last-mentioned Epoch It Is Continued Downwards In The Work, 1806-20, 17.1186–9, 1281, 1391; 19.61, 98.

[7] Johnstone’s wife later married Charles Edmund Nugent.