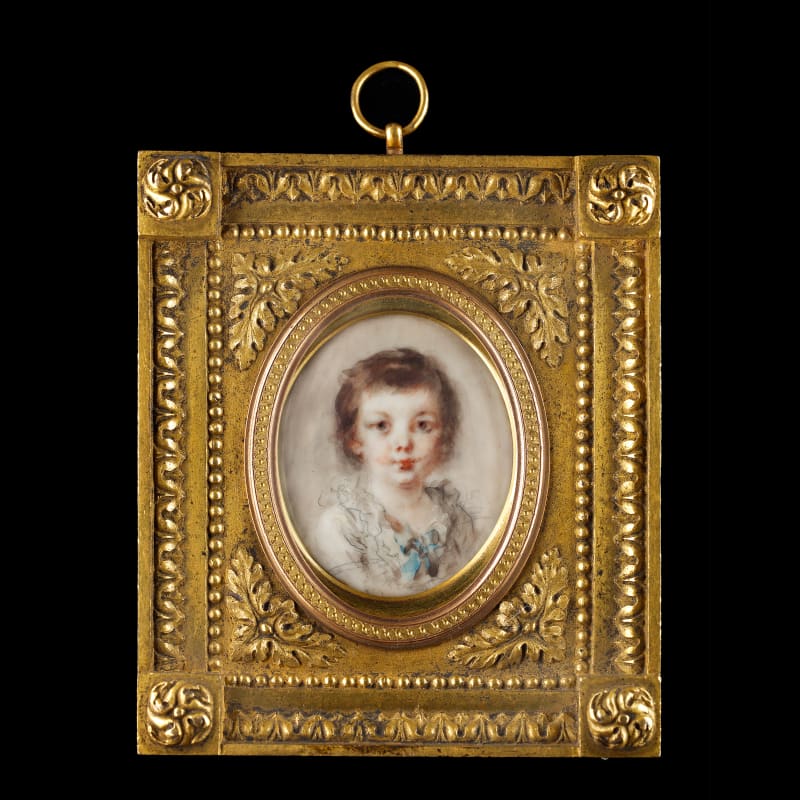

Richard Ottley was related to family in Pitchford, Shropshire but his branch of the family settled in St. Kitts, eventually acquiring land and properties in Antigua, St. Vincent, Tobago and Grenada. He married twice – first to Elizabeth Warner in 1753 and secondly in 1770 to Elizabeth Ottley nee Young (d. 1825)[1]. Their children included the well-known art connoisseur, painter, musician, and collector William Young Ottley (1771-1836).

Both William Young Ottley and his brother Warner went to St Vincent and Tobago where their father owned plantations. Later information on William Young and Warner has been difficult to clarify. In relation to William Young’s appointment in 1833 as Keeper of prints and drawings at the British Museum, a post that he accepted apparently for financial reasons, is often noted upon as Ottley refused, on principle, to accept any compensation for the losses caused him by the freeing of his slaves.[2] There is no doubt, however, that both sons benefitted from...

Richard Ottley was related to family in Pitchford, Shropshire but his branch of the family settled in St. Kitts, eventually acquiring land and properties in Antigua, St. Vincent, Tobago and Grenada. He married twice – first to Elizabeth Warner in 1753 and secondly in 1770 to Elizabeth Ottley nee Young (d. 1825)[1]. Their children included the well-known art connoisseur, painter, musician, and collector William Young Ottley (1771-1836).

Both William Young Ottley and his brother Warner went to St Vincent and Tobago where their father owned plantations. Later information on William Young and Warner has been difficult to clarify. In relation to William Young’s appointment in 1833 as Keeper of prints and drawings at the British Museum, a post that he accepted apparently for financial reasons, is often noted upon as Ottley refused, on principle, to accept any compensation for the losses caused him by the freeing of his slaves.[2] There is no doubt, however, that both sons benefitted from the proceeds of slavery, with William Young receiving £10,000 from his father’s will. His brother, Warner is said to have married a slave, Kitty Brown, and returned to England where they successfully sued the British Government for the salaries she lost between the change of law and this news reaching Tobago.[3]

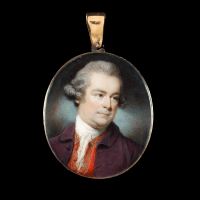

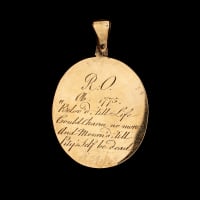

It appears that Richard Ottley was drawn and painted by Ozias Humphry many times, as this miniature is likely connected to a preparatory sketch by Humphry of 'Otley [sic] Esq.', which formed part of lot 400 in a sale held by Sotheby's in 1846 of the collection of the artist's natural child, William Upcott. This miniature is presumably one of those referred to by Humphry in an invoice dated April 1772: 'Mr Otley [sic] for four pictures £50 8s', painted just a few years before his early death in 1775 at the age of forty-six. Dying in his home in Argyll Street, Ottley also resided at Dunstan Park, Thatcham, Berkshire. As the provenance of this portrait shows that it was retained by the family for 186 years after Ottley’s death, it was likely worn initially by his wife as a bracelet and then engraved as part of the mourning following his death, before being passed down the generations.

By 1772, Humphry was established as one of the most successful and fashionable miniaturists in London. Shortly after he painted Ottley’s portrait, Humphry became a member of the Society of Artists in 1773. However, rebuffed by the woman he loved in 1771, he finally decided to leave England in 1773 and toured Europe for four years with the artist George Romney.

After his return to England, in 1779 Humphry was elected as an Associate of the Royal Academy – Academician status was to come in 1791 – but he felt that his professional opportunities were limited on his native soil. Thus, in 1785 the artist left for Calcutta. An uneasy couple of years followed in which Humphry found himself constantly looking over his shoulder to watch for the rivalry of established Madras-based miniaturist, John Smart. Never quite acquiring the success that he had hoped for – and that Smart achieved – Humphry returned to England in 1787.

Humphry initially returned to work as a miniaturist, yet in the 1790s this became increasingly untenable. His rapidly deteriorating eyesight caused his sitters to express their dissatisfaction at the quality of his likenesses. By 1797, Humphry had become almost totally blind. Robbed of his sight – the most vital tool of his profession – Humphry was forced into an unhappy retirement and died, impoverished, in 1810.

Ivory Act:

This artwork has been registered by Philip Mould and Company as qualifying as exempt from the ivory act. Please contact laura@philipmould.com if you have any further queries.

Ivory Registration: BBW4SKKS

[1] A portrait of Sarah attributed to Benjamin West hangs at LSU Museum of Art, Baton Rouge, USA.

[2] This appears to be based on a statement by J. Allen Gere, a claim repeated in e.g., the television documentary The Mystic Nativity, made by Fulmar and broadcast in December 2009. Information from The Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery at UCL (website accessed January 2022 https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/).

[3] It has not been possible to find evidence to back this claim, although the ‘Public Records Office’ apparently holds evidence that their mixed-race daughter attended school in England.