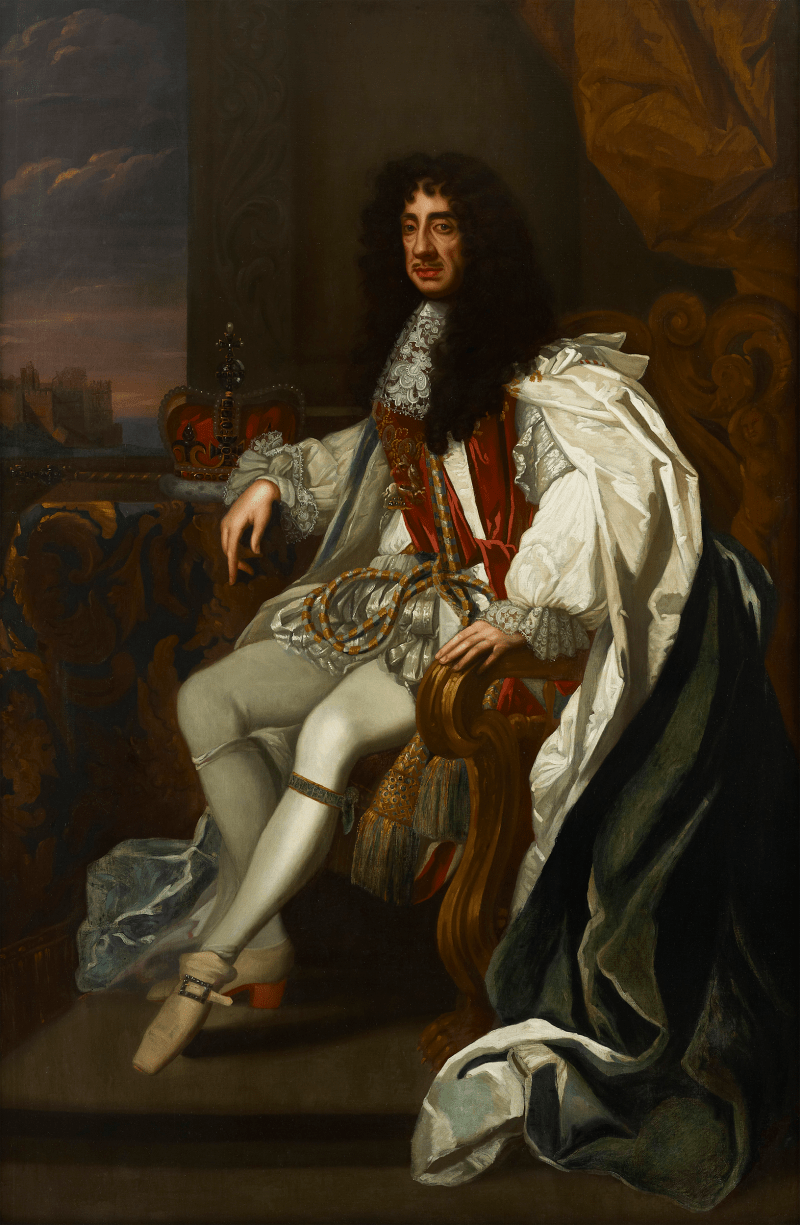

This tiny portrait belongs to a group of portraits painted by David des Granges during the prince’s exile to The Hague. This example would appear to date just prior to des Granges’s return to London in 1658 and the prince’s triumphant return to England in 1660, where he was crowned the following year.

Charles had a long association with des Granges, who had painted him as a young boy, copying portraits of him (the majority from the miniaturist John Hoskins) during the late 1630s. In 1647, he was perhaps the natural choice to follow the young Prince of Wales to The Hague. In 1651, he was appointed ‘His Majesty's Limner in Scotland’, the same year as Charles was crowned ‘King of Scotland’ at Scone. Although Charles could barely afford an official artist in his entourage, this post confirmed des Granges as an important supplier of images and a key part of his exiled court. These miniatures were essential...

This tiny portrait belongs to a group of portraits painted by David des Granges during the prince’s exile to The Hague. This example would appear to date just prior to des Granges’s return to London in 1658 and the prince’s triumphant return to England in 1660, where he was crowned the following year.

Charles had a long association with des Granges, who had painted him as a young boy, copying portraits of him (the majority from the miniaturist John Hoskins) during the late 1630s. In 1647, he was perhaps the natural choice to follow the young Prince of Wales to The Hague. In 1651, he was appointed ‘His Majesty's Limner in Scotland’, the same year as Charles was crowned ‘King of Scotland’ at Scone. Although Charles could barely afford an official artist in his entourage, this post confirmed des Granges as an important supplier of images and a key part of his exiled court. These miniatures were essential tools for distribution among his supporters. Not only were they given as tokens of affection and thanks but were essential in keeping the putative king’s visage alive. The particularly small size of this example may suggest that it was originally kept in a locket or set into a ring.

Many of des Granges’s miniatures of the prince were taken from a lost oil by Adriaen Hanneman (1601?-1671?). Des Granges’s petition to the king in 1671 requesting back payments for this group lists thirteen portrait miniatures of this type.[1] In 1655, Charles was based in Cologne, having moved from Paris where his mother, Henrietta Maria, was living. Des Granges’s whereabouts in 1655 is less certain, but it is probable that he followed the exiled court, only returning to London in 1658.[2] Documentary evidence certainly supports a continued requirement for portraits of the prince into the mid-1650s. In 1654, a letter from Charles in Paris to Jane Lane states, “Mistris Lane,…Your cousin will let you know that I have given order for my pickture for you; and if in this or in anything else I can shew the sence I have of that wch I owe you, pray lett me know it, and it shall be done. Your most assured and constant friend, Charles R.”.[3] It is not known what form this ‘pickture’ of the king took, but it is likely to have been a miniature (one was certainly in possession of the family until its later destruction by fire). For practical reasons miniatures were cheaper to produce and easier to transport than other forms of portrait.

Des Granges’s career continued through the Restoration, although he was not awarded a salaried position at court. There is no doubt that des Granges was a loyal servant to Charles, painting his portrait to order with little hope of financial gain from the exiled monarch. His petition to the king in 1671, requesting payment twenty years later, states that he had been ‘…forced to rely on the charity of well-disposed persons’ to survive.[4]

[1] Examples can be found at Ham House (National Trust) and the National Portrait Gallery, London as well as numerous private collections.

[2] The London periodical Mercurius Politicus states that in July 1658, after a period of time away, des Granges was residing near the Fountain tavern in the Strand.

[3] Katharine Gibson, “Best belov’d of kings”: the iconography of King Charles II, Thesis (D.Phil.), 1997, p.45, copy of a letter shown to the author

[4] R. W. Goulding, ‘The Welbeck Abbey miniatures’, Walpole Society, 4 (1914–15), p.29