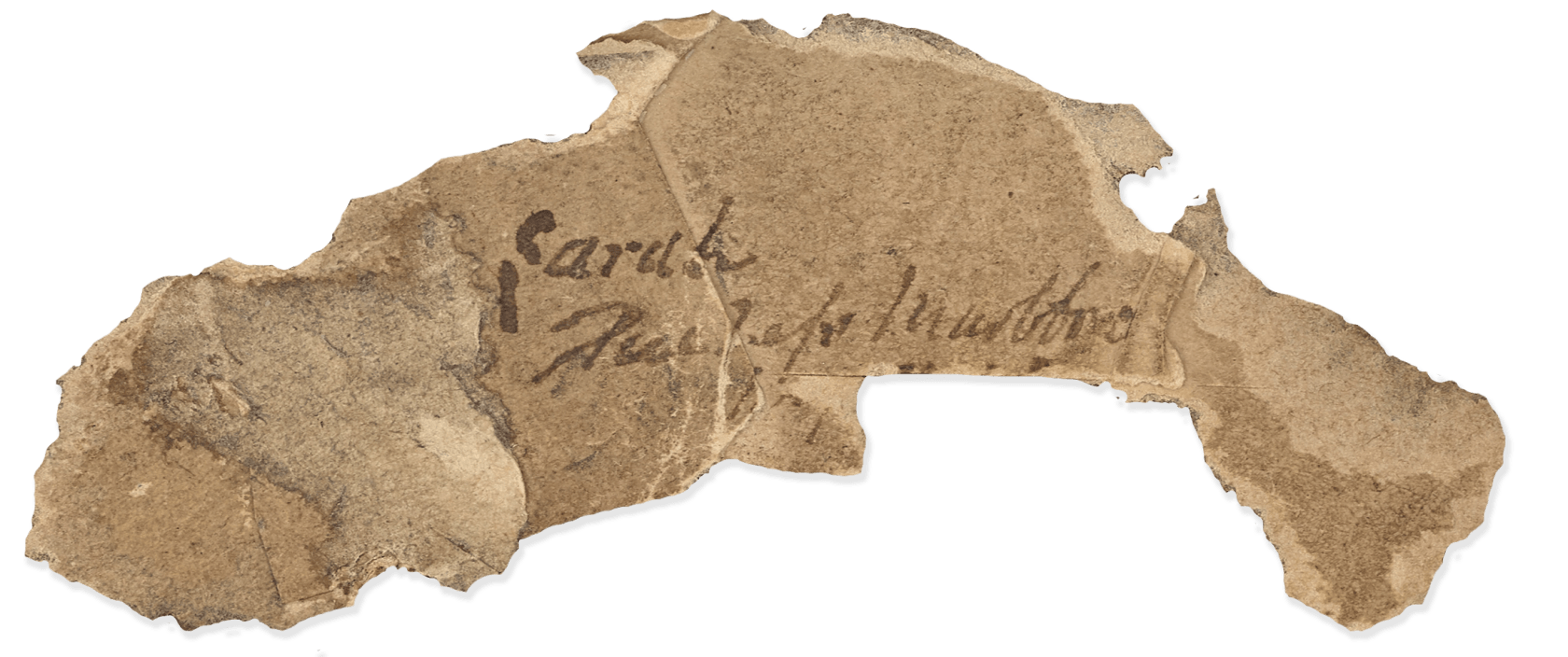

Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough (1660-1744), reclining on a red cushion, the landscape background with an arch and fountain in formal grounds, possibly the Triumphal Arch at Blenheim Palace[1]

This portrait of Sarah Churchill (née Jenyns), Duchess of Marlborough, seems to be an original composition by the French-born artist Louis Goupy. Goupy would have been well-placed to access portraits of the Duchess, being a subscriber (from 1711) to the new academy of painting started by Sir Godfrey Kneller in Great Queen Street. Here the duchess is shown in a pose first painted by Kneller in 1708 (Althorp), and later engraved by John Simon (1675-1751) (engraving circa 1700-1725, NPG D32565). The present portrait differs from Kneller’s version with the duchess’s head more inclined and the inclusion of architectural features – possibly those of the still work-in-progress Blenheim Palace (completed 1725) – in the background. It must pre-date the death of the Duke of Marlborough (1722) but post-date the death of Queen...

Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough (1660-1744), reclining on a red cushion, the landscape background with an arch and fountain in formal grounds, possibly the Triumphal Arch at Blenheim Palace[1]

This portrait of Sarah Churchill (née Jenyns), Duchess of Marlborough, seems to be an original composition by the French-born artist Louis Goupy. Goupy would have been well-placed to access portraits of the Duchess, being a subscriber (from 1711) to the new academy of painting started by Sir Godfrey Kneller in Great Queen Street. Here the duchess is shown in a pose first painted by Kneller in 1708 (Althorp), and later engraved by John Simon (1675-1751) (engraving circa 1700-1725, NPG D32565). The present portrait differs from Kneller’s version with the duchess’s head more inclined and the inclusion of architectural features – possibly those of the still work-in-progress Blenheim Palace (completed 1725) – in the background. It must pre-date the death of the Duke of Marlborough (1722) but post-date the death of Queen Anne (1714). It may have been painted during the final years of the building of Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire, which was finally completed after the Duke and Duchess’s return to England after their self-imposed exile in Holland.

Louis Goupy is also said to have been a pupil and nephew of Bernard Lens (1681-1740), who painted a large, full length, vellum miniature of the duchess dated 1720, in a similar pose, but with a miniature of the Duke of Marlborough on her wrist (V&A 627-1882).

Sarah Churchill (née Jenyns) was, unquestionably, one of the most extraordinary women of her age. Born into an impoverished gentry family, Sarah made her name at court when in 1673 she entered into the service of Mary of Modena (1658-1718), wife of James, Duke of York, later James II (1633-1701). Independent, strong-willed and assertive, she went as far as to have her mother banished from court when she objected to her marriage to the similarly impoverished John Churchill (1650-1722) (formerly the lover of the Duchess of Cleveland (c.1640-1709), a mistress of Charles II (1630-1685)), whose impecuniousness meant that she feared the match would do little to improve the family’s fortunes.

Her mother could not, however, have been more mistaken. Churchill’s rise at court was meteoric. A shrewd politician, he positioned himself to gain a peerage from James II before abandoning him in favour of Prince William of Orange (1650-1702), who, following the success of the Glorious Revolution of 1688, replaced the Catholic James to become the new, emphatically Protestant King of England. For his loyalty, William rewarded Churchill by making him Earl of Marlborough. From this point, he became one of the most powerful figures in the realm, and his stock was only to continue to rise. In 1704, he commanded the victorious British forces at the Battle of Blenheim, thwarting the ambitions of Louis XIV of France and winning him a dukedom from a grateful nation.

Marlborough and Sarah were well matched both in their ambition and in their political alacrity. In tandem to Marlborough’s rise, Sarah had shrewdly befriended James’s daughter by his first, Protestant wife, Anne (1665-1714). Following the arrival of William, who was married to Anne’s sister Mary (1662-1694), she became again one of the major figures of the court – her status having fallen following the birth of James’s son by Mary of Modena. Following her appointments, first, as a lady of the bedchamber and, then, as Anne’s Groom of the Stool, Sarah obtained an emotional (and physical) proximity to Anne that few could rival. Anne came to be dependent on Sarah, turning to her for advice and counsel. Indeed, so strong was their bond that Anne fell profoundly in love with Sarah.

But the relationship was an unequal one. Their characters were incompatible: Sarah, a voracious reader, was fiercely intelligent, whilst Anne had no particular intellectual ambitions. Further, although their affection was certainly mutual, Sarah never loved Anne in the way that she did her. And the result was tempestuous. Following William’s death and Anne’s subsequent coronation as queen on St George’s Day in 1702, Sarah became by far the most powerful of Anne’s advisors; in the words of her biographer, ‘those who wanted to access Anne had to go through Sarah first’.[2] With this influence, she became increasingly self-confident and, convinced of her intellectual superiority, assertive, even domineering. But, she also became complacent and failed to realise that she had come to be replaced in the Queen’s affections by Abigail Hill (c.1670-1734), a cousin of Sarah’s that she herself had introduced to the court.

Following a series of bitter rows about Abigail Hill’s position, Sarah met Anne for the last time in 1710. They would from this point communicate only in writing. Following the election of the Tory party later in 1710, the next year Sarah – a staunch Whig – was stripped of all of her positions at court. When she was forced to leave her rooms in St James’s Palace, the furious Duchess of Marlborough took with her all of their furnishings, including the door locks (she even contemplated taking the chimney-breast). It seems that she was only allowed to keep the money that had been granted her in happier days to build Marlborough House, opposite St James’s, to prevent her from leaking Anne’s love letters.

Following a year spent in Holland – where her husband was already living in exile – the Duke and Duchess of Marlborough returned to Britain in 1714 to find Anne dead. But the, Hanoverian dynasty refused to allow them to enjoy the power they had enjoyed under Anne’s reign, so the couple retired to their residence, the vast pile of Blenheim Palace, which had been paid for by the nation in thanks for Marlborough’s victories.

[1] The statues seen on the top of this arch may have been removed, as were those flanking the portico, in the 1770s, some being used on the East Gate and others placed in the garden.

[2] J. Falkner, ‘Churchill [née Jenyns], Sarah, duchess of Marlborough (1660–1744)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography [online edn.], 2008.