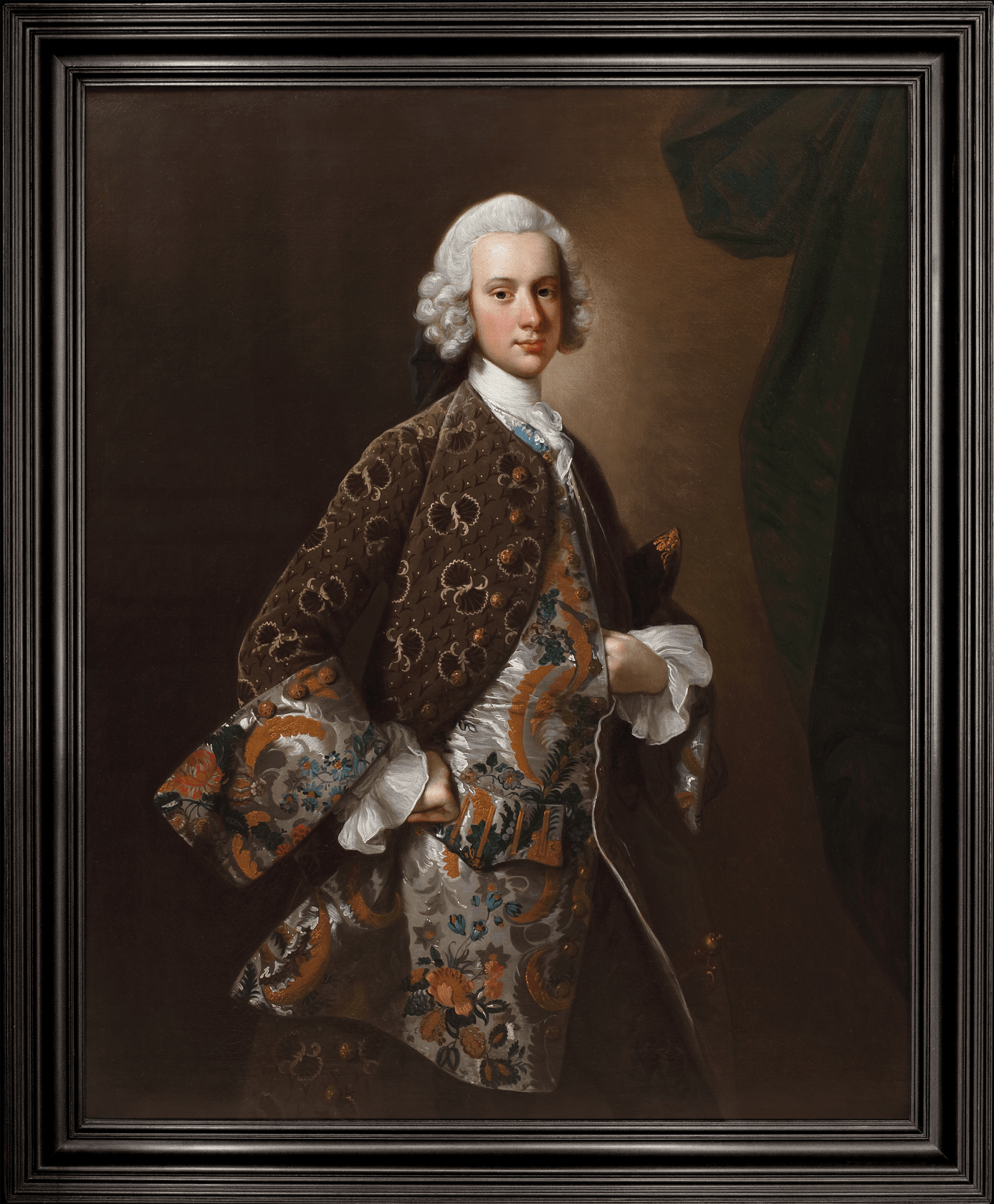

This exceptionally well-preserved portrait by Thomas Hudson is a rare portrayal of Georgian male fashion at its most opulent. Hudson was one of the most prominent portraitists of his generation, shaping the image of Britain’s elite in the mid-eighteenth century. Technically assured and theatrically composed, this work shows Hudson at the height of his powers and is unmatched in its sartorial grandeur.

This portrait exemplifies Hudson’s mastery, depicting a figure whose elegance and confidence seem to effortlessly encapsulate the fashionable virtues of the period. The gentleman’s attire exemplifies the habit à la française – coat, waistcoat, and breeches – of extreme quality. The coat is patterned with stylised wheat sheaves and floral motifs, hallmarks of the Rococo aesthetic, and appears to be made of a woven silk or silk velvet. The most distinctive garment of the ensemble is the waistcoat, woven in silver and white, which features polychrome flowers, golden curls and foliate motifs, possibly embroidered over the already...

This exceptionally well-preserved portrait by Thomas Hudson is a rare portrayal of Georgian male fashion at its most opulent. Hudson was one of the most prominent portraitists of his generation, shaping the image of Britain’s elite in the mid-eighteenth century. Technically assured and theatrically composed, this work shows Hudson at the height of his powers and is unmatched in its sartorial grandeur.

This portrait exemplifies Hudson’s mastery, depicting a figure whose elegance and confidence seem to effortlessly encapsulate the fashionable virtues of the period. The gentleman’s attire exemplifies the habit à la française – coat, waistcoat, and breeches – of extreme quality. The coat is patterned with stylised wheat sheaves and floral motifs, hallmarks of the Rococo aesthetic, and appears to be made of a woven silk or silk velvet. The most distinctive garment of the ensemble is the waistcoat, woven in silver and white, which features polychrome flowers, golden curls and foliate motifs, possibly embroidered over the already intricate textile. This level of finery closely aligns with the garments worn at the court of King George II, particularly during state occasions such as royal birthdays, when attendees dressed with extraordinary flair.

Such lavish dress is rare in British portraiture at this date. Even within Hudson’s own extensive body of work, few portraits match this level of extravagance, as the prevailing aesthetic of portraiture of the period leaned towards a more understated elegance. This sitter, by contrast, appears to embrace bold continental tastes. His clothing suggests not only wealth, but travel and connoisseurship. His garments were possibly acquired during a Grand Tour, where French and Italian tailoring was more ornate than its British equivalent. His powdered wig, tied in the bag style to prevent the powder from falling on the valuable textiles, was typical of the late 1740s to early 1750s and complements the overall sense of formality.

The excellent condition of this work allows a rare opportunity to appreciate Hudson’s skills while also reminding us of the collaborative nature of portrait painting at this date. Such was the demand for Hudson’s work that he relied heavily on the cooperation of studio assistants and drapery painters to embellish his portraits with the shimmering silks that his patrons demanded. One such painter was Joseph van Aken (c. 1699–1749), a Flemish artist who arrived in London around 1720 and quickly became the leading drapery painter for fashionable portraitists. It was well-known that Hudson harnessed Van Aken’s talents and in 1744, George Vertue noted: ‘It is truly observd that Hudson has lately more success and approbation than the other or any other of ye busines – at present a great Run – his pictures being dressd and decorated by Mr Joseph Van Aken – who is a very elegant and ingenious painter. Serves & helps him and other painters to dress and set off their pictures to advantage he having an excellent free Genteel and florid manner of pencelling Silks Sattins Velvets. Gold laceings Carvings &c.’[1] Whether Van Aken collaborated on the present work is unknown, not least because he died around the time it was painted, but the skilful rendering of the costume indicates the hand of a highly-trained artist.

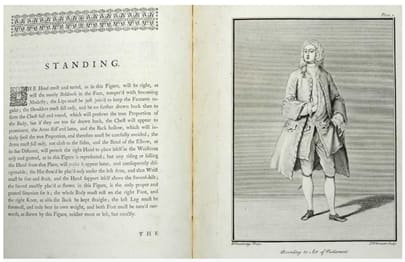

Although the identity of the present gentleman has so far eluded scholars, his deportment tells that both he and the artist were well-versed in the codes of elite conduct and presentation. He is positioned en chapeau bras, with one arm holding a tricorn hat and the other hand tucked into his waistcoat. He adopts a variation of the free and easy motions of the arms as advised and illustrated in François Nivelon’s The Rudiments of Genteel Behaviour [Fig. 1]. In his quiet confidence and carefully assembled elegance, he is the embodiment of mid-century refinement.

[1] George Vertue, eds. L. Cust and A. Hind, ‘The Notebooks of George Vertue III’, The Walpole Society. London, 1933, p.123.