We are grateful to Dr. Jo Cottrell for her assistance when cataloguing this work.

Portrait of a Woman is the most important work by Jessica Dismorr to appear on the market in recent years. It was exhibited in the Group X exhibition of 1920, in which Dismorr was the sole female contributor, and is a rare survival from this short-lived artistic movement.

As one of only a handful of surviving works from Dismorr’s late-Vorticist phase, the present work is crucial to understanding her art and legacy. A founding signatory of BLAST and active participant in Vorticism, Dismorr forged her own path amid a movement that was both revolutionary and profoundly male-dominated. The present work, which was retained by the artist until her death, reveals her distinctive synthesis of the stylistic vocabulary associated with Vorticism, with an introspective and distinctly female perspective.

The Group X exhibition, held at the Mansard Gallery in March–April 1920, was established in the wake of Vorticism’s...

We are grateful to Dr. Jo Cottrell for her assistance when cataloguing this work.

Portrait of a Woman is the most important work by Jessica Dismorr to appear on the market in recent years. It was exhibited in the Group X exhibition of 1920, in which Dismorr was the sole female contributor, and is a rare survival from this short-lived artistic movement.

As one of only a handful of surviving works from Dismorr’s late-Vorticist phase, the present work is crucial to understanding her art and legacy. A founding signatory of BLAST and active participant in Vorticism, Dismorr forged her own path amid a movement that was both revolutionary and profoundly male-dominated. The present work, which was retained by the artist until her death, reveals her distinctive synthesis of the stylistic vocabulary associated with Vorticism, with an introspective and distinctly female perspective.

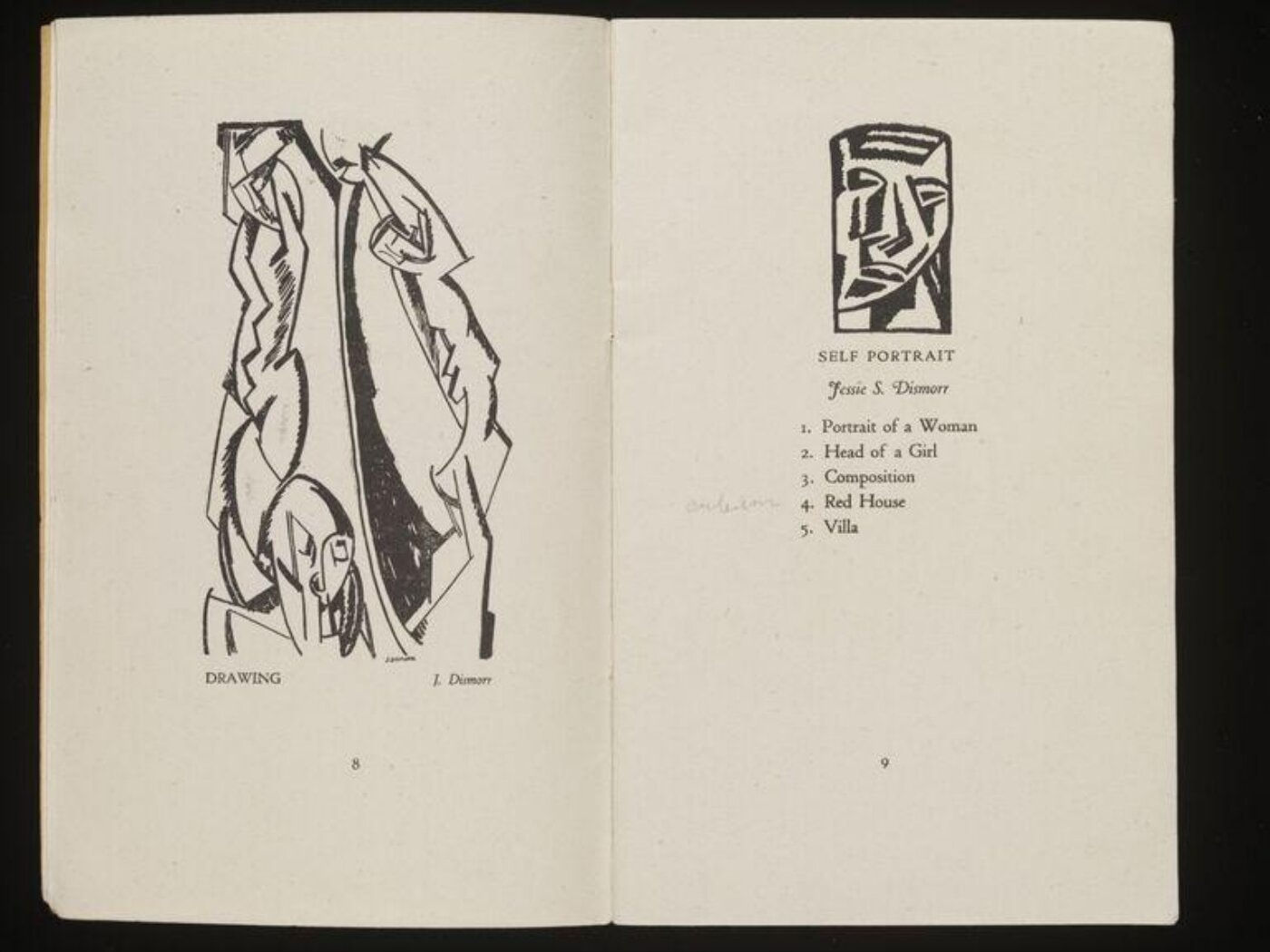

The Group X exhibition, held at the Mansard Gallery in March–April 1920, was established in the wake of Vorticism’s dissolution during the First World War, as a platform for avant-garde artists committed to modernist experimentation. Dismorr was the sole female exhibitor, showing five works (recorded in the exhibition’s catalogue) and a now lost self-portrait [fig. 1]. Contemporary reviews of the exhibition were mixed, reflecting the radical nature of the work: Truth described her ‘distortions’ as ‘distressing,’[1] while the Educational Times noted her success in creating works ‘very perfect Dada’[2] and the Bystander remarked on the group’s deliberate rejection of traditional beauty.[3] These responses reveal the degree to which Group X challenged prevailing artistic conventions, and Dismorr’s participation placed her firmly at the centre of Britain’s most progressive currents. After the Group X exhibition, Dismorr did not exhibit artwork for four years.[4]

The sitter in Portrait of a Woman Seated is the artist’s sister, Margaret Thompson (née Dismorr), though it was formerly misidentified as Helen Saunders, another key female Vorticist and inscribed as such on the reverse, likely around the time it was exhibited at the Mercury Gallery in 1974.[5] In a letter in the Tate archive, Margaret clarifies her identity: ‘[It] sounds like a reminder of the day about 1920 when Jessie and Wyndham Lewis painted me in a voluminous blue dress, probably in his studio.’[6] Another letter adds fascinating context to the sitting itself: “Did Wyndham Lewis and Jessica do separate portraits of me? Yes. When I sat for them, each painted a separate study at a separate easel. The studio was plain, was unknown to me, so probably was Lewis’s.”[7]

The survival of much of Dismorr’s early works is owed entirely to her sister Margaret. In 1920, the year this work was exhibited, Margaret visited her sister and was shocked to see many of her wooden panel paintings strewn across the studio floor, ready to be thrown out. She persuaded her sister to save them, but only on the condition that they be taken to America and never publicly shown.[8] Magaret later recalled: “They came into my possession at my request because discarded by Jessica who disapproved their old fashioned style when she changed to Vorticism. Jessica in London gave them to me because I had begun to live permanently in America where she could trust that they would never be publicized nor known as her work.”[9]

In this portrait, Margaret is poised yet tense in posture, with her right arm resting on a chair and her left hand folded across her lap. The angular articulation of face and limbs, the muted palette, and the interplay of light across faceted planes demonstrate Dismorr’s integration of Vorticist structure with the genre of portraiture. The simplified drapery behind the sitter heightens the figure’s sculptural solidity and psychological intensity. Here, Dismorr synthesises the formal Vorticist principles of geometric structure and planar articulation, with an intimate, introspective gaze, resulting in a portrait that is at once innovative and emotional.

The painting’s origins in a joint sitting with Wyndham Lewis, the self-proclaimed principal theorist of Vorticism, is significant, particularly in light of Lewis’s misogynistic reputation. His relationship with Dismorr was inconsistent and sometimes turbulent; although he actively supported and praised her work, he also diminished her contributions in his later writings and public accounts of Vorticism’s history. In works such as The Demon of Progress in the Arts (1957), he cast her as a peripheral figure, reinforcing a male-dominated narrative that excluded the women who had helped define the movement’s visual identity. That this work was created in parallel with Lewis points to reciprocal influence, in which Dismorr’s practice may have informed as much as it reflected the movement’s direction.

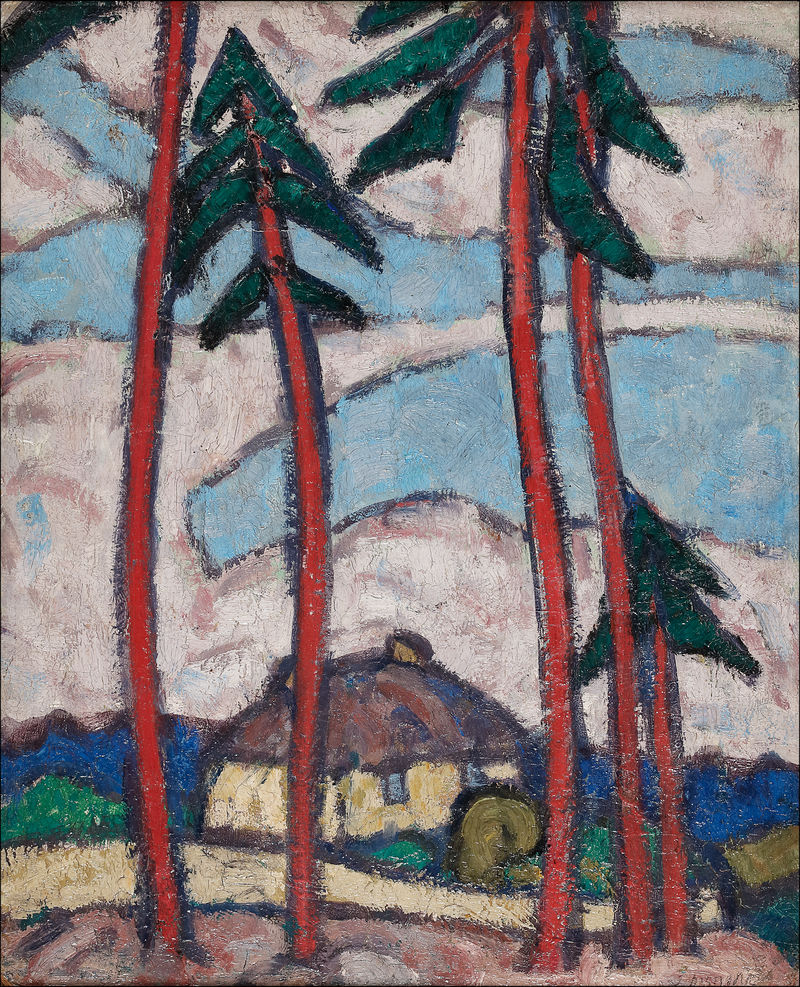

Technical analysis by The Courtauld Institute has added further complexity to this painting’s history, revealing that Dismorr worked over an earlier composition of a landscape of houses on a hillside [fig. 2]. While her reasons for abandoning the scene remain unknown, it is tempting to see in the substitution her resolve to devote the canvas to a more ambitious modernist composition, particularly given her attempted destruction for her earlier oeuvre. This discovery takes on particular resonance in the wake of the Courtauld’s 2020 discovery of a long-lost painting by Helen Saunders beneath Lewis’s Praxitella.[10]

This painting underscores Dismorr’s contribution to early twentieth-century modernism, offering crucial insight into her role within Vorticism and post-Vorticist circles. Portrait of a Woman is not only a testament to Dismorr’s technical skill and innovative vision but also a valuable document for scholarship on modernist experimentation in London between the wars.

[1] Truth. Wednesday 07 April 1920, p.668.

[2] Educational Times. Saturday 01 May 1920, p.213.

[3] The Bystander. Wednesday 21 April 1920, p.199.

[4] Alicia Foster, (2019) Radical Women: Jessica Dismorr and her Contemporaries. London: Lund Humphries, p.53.

[5] This identification is supported by Brigid Peppin and Quentin Stevenson.

[6] Margaret Thompson, Letter to William Lipke. TGA 8223.

[7] Margaret Thompson, draft notes for inclusion in a letter to William Lipke, 3 November 1965, Private Collection.

[8] Quentin Stevenson, Looking for Jessica Dismorr, p. 24, Private Collection.

[9] Margaret Thompson, draft letter to William Lipke, 3 November, 1965, Private Collection.

[10] See: Rebecca Chipkin and Helen Kohn, (2020) ‘Beneath Wyndham Lewis’s Praxitella: The Rediscovery of a lost Vorticist work by Helen Saunders’, The Courtauld Institute of Art.