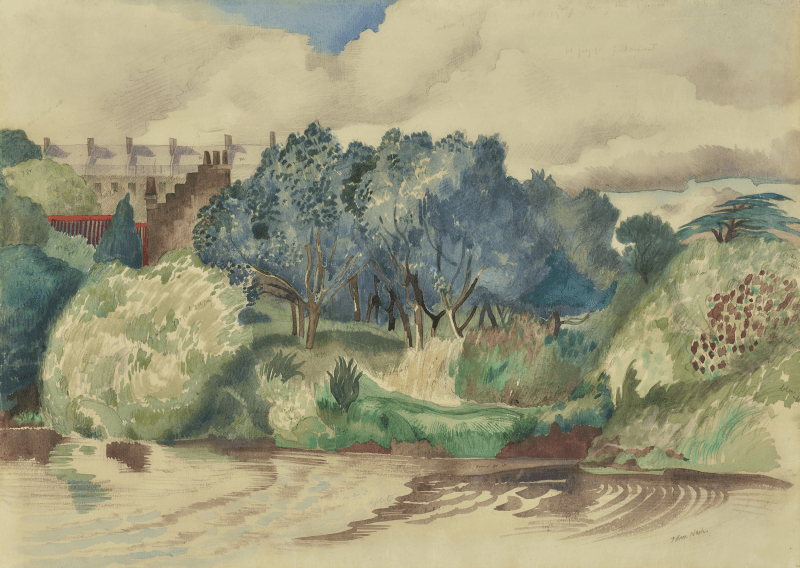

Direct and honest, John Nash’s distinctly British landscape foregrounds a stack of wood rendered in autumnal tones. Many of Nash’s landscapes from the 1950s and 1960s depict subtle traces of human intervention within the natural landscape; a country road winding through fields, the arch of a bridge gliding over a river, or a recently chopped tree trunk. In this instance, the shed in the background distinguishes this painting as an openly domestic setting, further highlighted by the neatly cut grass behind the woodpile.

In his chapter on Nash in ‘Unquiet Landscape: Places and Ideas in 20th Century British Painting’, Christopher Neve asserts:

His landscape is essentially a man-made one: the evidence of man’s detailed and persistent cultivation as hedger, ditcher, sower, and ploughman, is everywhere, but it is as though man himself has just left the scene … The only figure in the landscape is Nash himself, the viewer, and the degree of introspection implied by the painting makes...

Direct and honest, John Nash’s distinctly British landscape foregrounds a stack of wood rendered in autumnal tones. Many of Nash’s landscapes from the 1950s and 1960s depict subtle traces of human intervention within the natural landscape; a country road winding through fields, the arch of a bridge gliding over a river, or a recently chopped tree trunk. In this instance, the shed in the background distinguishes this painting as an openly domestic setting, further highlighted by the neatly cut grass behind the woodpile.

In his chapter on Nash in ‘Unquiet Landscape: Places and Ideas in 20th Century British Painting’, Christopher Neve asserts:

His landscape is essentially a man-made one: the evidence of man’s detailed and persistent cultivation as hedger, ditcher, sower, and ploughman, is everywhere, but it is as though man himself has just left the scene … The only figure in the landscape is Nash himself, the viewer, and the degree of introspection implied by the painting makes the possibility of intrusion by other people almost alarming.[1]

This astute description of his work offers an apposite reflection on the present landscape. The effect of human intervention is notable but does not overpower the scene. Rhythmic compositional devices have been implemented in the forefront to foreground the influence of nature; repetitive curls of paint illustrate the unfurling mushrooms growing from the log pile. Nash was a staunch plantsman with an observant interest in botany. His understanding of plants aided his artwork and drove his draftsmanship beyond solely imitative realism. In his seminal book on Nash ‘John Nash: Artist & Countryman’, Andrew Lambirth aligns Nash’s work to that of his forerunners Jean-François Millet, Gustave Courbet, and particularly John Constable, who held the position that painting was ‘an art that is to realise and not feign’. On Nash, Lambirth asserts; ‘Painting was about shaping but not forcing nature into a pattern … seeking the abstract structure beneath the surface detail, and interpreting without forfeiting character. Echo, rhythm, repetition were sought out, but not emptied of meaning or naturalness.’[2]

As a keen plantsman, Nash was au fait with nature’s unpredictable tendencies. Much like artist-plantsman, Cedric Morris, Nash’s horticultural practice informed his artistic practice and vice versa. From the early 1920s, Nash had been designing and creating gardens and subsequently became a renowned figure in the horticultural world as a judge at Chelsea Flower Show.

Two years after this landscape was completed, Nash was appointed a CBE in 1964. In 1967, the Royal Academy of Arts granted him the first-ever retrospective exhibition of a living painter and his work can now be found in many private and public collections such as the Tate Gallery, the Courtauld Institute of Art, the Fine Art Museums of San Francisco and the Government Art Collection.

[1] Neve, C. (2020) Unquiet Landscape: Places and Ideas in 20th Century British Painting. London: Thames and Hudson, p. 65.

[2] Lambirth, A. (2019) John Nash: Artist & Countryman. Norwich: Unicorn Press, p. 17 & 268.