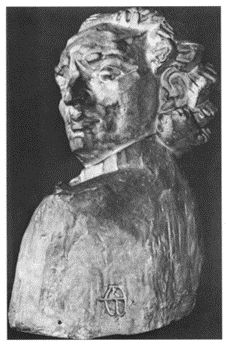

This ground-breaking portrait by Alfred Wolmark is the first of two oil portraits of Henri Gaudier-Brzeska by Wolmark, and the only one in private hands.[1] It was given by the artist to Gaudier-Brzeska as a gift in return for a larger than life-size bust of Wolmark by Gaudier-Brzeska, depicted in the background of this work [figs. 1 and 2].

This portrait offers a complex examination of the relationship between artist and sitter. Although portraying Gaudier-Brzeska and Wolmark, it simultaneously represents the process of dual artistic creation, pushing it beyond a double portrait into the realm of subject painting or allegory. Wolmark presents Gaudier-Brzeska in the act of sculpting, holding his tools, as a craftsman deeply engaged in the physical act of creation. In his left hand he holds what appears to be a painted figural sculpture. He also incorporates a self-referential element through Gaudier-Brzeska’s sculpture of Wolmark. Modelled in clay and cast as a unique plaster, it was larger than...

This ground-breaking portrait by Alfred Wolmark is the first of two oil portraits of Henri Gaudier-Brzeska by Wolmark, and the only one in private hands.[1] It was given by the artist to Gaudier-Brzeska as a gift in return for a larger than life-size bust of Wolmark by Gaudier-Brzeska, depicted in the background of this work [figs. 1 and 2].

This portrait offers a complex examination of the relationship between artist and sitter. Although portraying Gaudier-Brzeska and Wolmark, it simultaneously represents the process of dual artistic creation, pushing it beyond a double portrait into the realm of subject painting or allegory. Wolmark presents Gaudier-Brzeska in the act of sculpting, holding his tools, as a craftsman deeply engaged in the physical act of creation. In his left hand he holds what appears to be a painted figural sculpture. He also incorporates a self-referential element through Gaudier-Brzeska’s sculpture of Wolmark. Modelled in clay and cast as a unique plaster, it was larger than life-size and exhibited by Gaudier Brzeska with the Allied

Artists Association Exhibition in 1913. [2],[3] Wolmark may have painted the present portrait as a return gesture and it was exhibited in the same year at the International Society Exhibition at the Grosvenor Gallery, London.

At this date, Wolmark was already an established painter. Gaudier himself, having only arrived in London in 1911, was still an aspiring artist struggling to garner commissions. Afflicted by abject poverty, his frayed shirts and bohemian appearance alarmed the upper echelons of society, whose commissions he coveted.[4] To financially facilitate his artistic ambitions, he worked as a clerk in the City of London and frequented local public houses, offering to draw customers for a penny each. Wolmark was fundamental in establishing Gaudier-Brzeska’s career and supported his entry into modernist circles by introducing him to potential clients.[5] Gaudier’s partner, Sophie Brzeska, kept a journal which has become a crucial primary source documenting the friendship between Wolmark and Gaudier. It details conversations and debates between the artists, particularly regarding their views on portraiture and the purpose of art, as well as recording a firsthand impression of the present painting.[6] Although this may appear unlikely given the monumental scale, the extract suggests that the painting was completed in one day in the summer of 1913. Gaudier-Brzeska reported; ‘it is a completely different style from anything Wolmark has done till now.’[7]

Many popular portrait artists at this time, such as John Singer Sargent, continued to celebrate upper-class men in ways that emphasised traditional masculine virtues - dignity, control, and status. However, the present work celebrates a newly emerging notion of popular masculinity. Art historian Evelyn Silber states: ‘Almost everything about this portrait is aggrandising: Gaudier’s torso, the scale of the sculpture – embodying the modern sculptor in an image that pays homage to the classical tradition of depicting artists with the tools of their trade, while undermining the gentlemanly pretensions and decorum such portraits usually conveyed.’[8] This aggrandising and semi-erotic depiction breaks from traditional, genteel depictions of artists emphasising instead the raw, intense nature of the sculpting process.

[1] The later full-length portrait is in the collection of the Musée des Beaux-Arts d'Orléans [fig 3].

[2] Patrick Elliot, (2004) Burlington Magazine. CXLVI, 1221, December, p.819.

[3] The bronze casts are now in public collections including The National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh and The Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

[4] H. E. Ede, Savage Messiah. Cambridge: Kettle’s Yard and Henry Moore Institute, 2011, p.42

[5] Evelyn Silber, (2004) ‘Three Portraits and a friendship: Wolmark and Gaudier-Brzeska’, in Rediscovering Wolmark: A Pioneer of British Modernism, 2004-05. London: Ben Uri Gallery.

[6] ‘Sophie Brzeska: short stories and diary’, Cambridge University Library, Add. Ms 8554; Evelyn Silber, (2004) ‘Three Portraits and a friendship: Wolmark and Gaudier-Brzeska’, in Rediscovering Wolmark: A Pioneer of British Modernism, 2004-05. London: Ben Uri Gallery.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Evelyn Silber, (2004) ‘Three Portraits and a friendship: Wolmark and Gaudier-Brzeska’, in Rediscovering Wolmark: A Pioneer of British Modernism, 2004-05. London: Ben Uri Gallery, p.26.