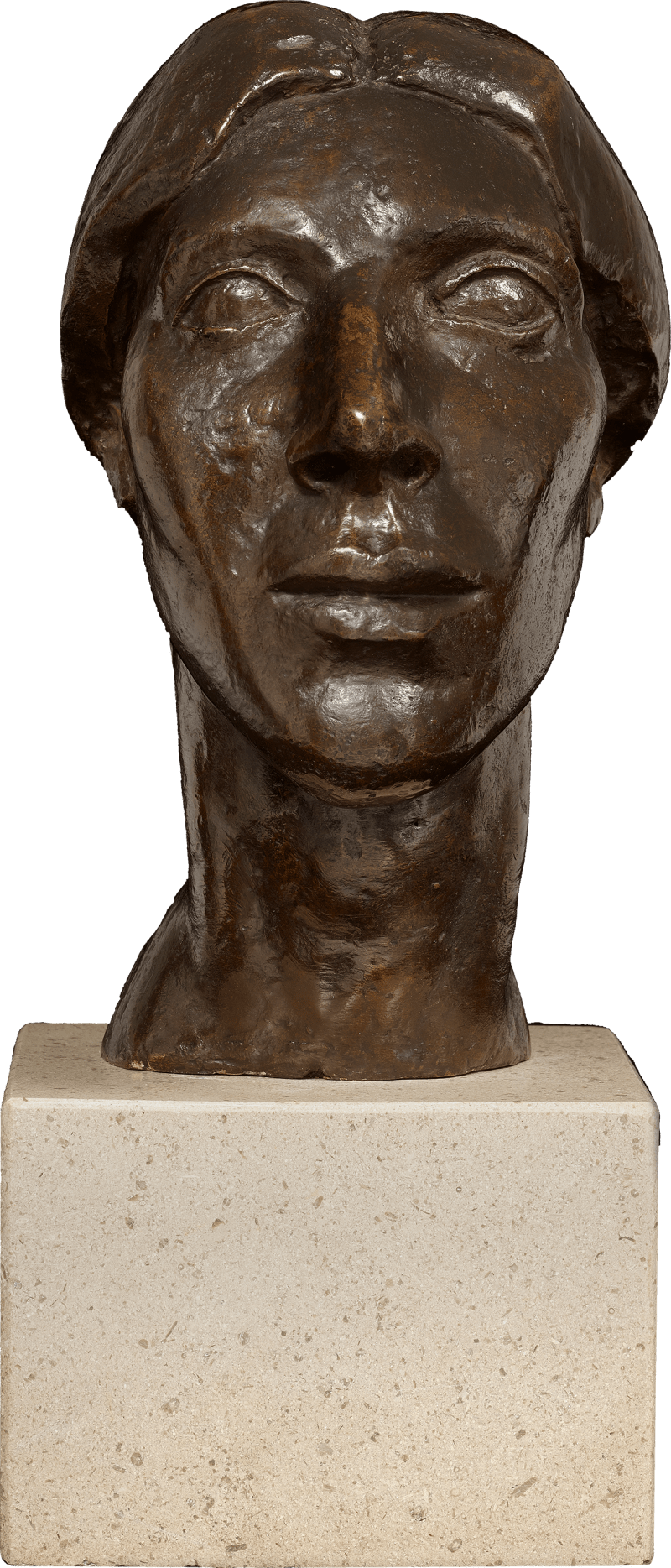

This portrait of the artist’s wife was completed the year after their marriage. Sculpted during what Tomlin described as the happiest point of his life, it expresses a moment of joy and clarity within the artist’s otherwise turbulent life.

Stylistically, it marks an interesting departure from Tomlin’s early technique, in which he left visible the rough marks of the individual clay pellets he pressed into the surface of his sculptures. Another glazed cast of this sculpture was painted by Duncan Grant, who also decorated the detachable base in his characteristically decorative motifs [fig. 1].

Julia Strachey was a member of the prominent Strachey family. She was the daughter of civil servant Oliver Strachey and the influential Ray Strachey (born Rachel Pearsall Conn Costelloe), who dedicated her life to women's suffrage. Julia Strachey herself was somewhat of a polymath, excelling in writing, acting, painting and music. Throughout her early adulthood, she struggled to discern which of these talents to pursue...

This portrait of the artist’s wife was completed the year after their marriage. Sculpted during what Tomlin described as the happiest point of his life, it expresses a moment of joy and clarity within the artist’s otherwise turbulent life.

Stylistically, it marks an interesting departure from Tomlin’s early technique, in which he left visible the rough marks of the individual clay pellets he pressed into the surface of his sculptures. Another glazed cast of this sculpture was painted by Duncan Grant, who also decorated the detachable base in his characteristically decorative motifs [fig. 1].

Julia Strachey was a member of the prominent Strachey family. She was the daughter of civil servant Oliver Strachey and the influential Ray Strachey (born Rachel Pearsall Conn Costelloe), who dedicated her life to women's suffrage. Julia Strachey herself was somewhat of a polymath, excelling in writing, acting, painting and music. Throughout her early adulthood, she struggled to discern which of these talents to pursue professionally and instead immersed herself within the glittering 1920s world of the ‘Bright Young Things’, frequenting nightclubs in London and the rooms of college men in Oxford. When, in 1925, she was forced to move back in with her father at Gordon Square, it was her uncle Lytton Strachey and Dora Carrington who helped to restore her joie de vivre. Their newly acquired home, Ham Spray, in Wiltshire became her point of refuge where she met her future husband, Stephen Tomlin.[1]

Both Tomlin and Strachey spent the long summers of 1925 and 1926 at Ham Spray. Although her uncle Lytton found her to be ‘a strange bird but with habits unlike any other bird’, Tomlin became increasingly infatuated and wrote her frequent love letters during their time apart.[2] By Christmas 1926, the couple decided to live together in Paris over the winter, renting a studio and ‘trialling’ married life.[3] Regrettably, news of the unmarried couples’ cohabitation shocked the Tomlin and Strachey families which likely accelerated their engagement and swift marriage. They were wedded on 22 July in St Pancras Church, London and moved to Mill Cottage in Swallowcliffe, Wiltshire, where the present bust was executed.

The newly married couple considered these early years at Swallowcliffe some of the happiest of their lives, particularly Tomlin [fig. 2]. Strachey was permitted the time and space to concentrate on her writing and diligently focused on her own productivity, beginning each diary entry with the number of pages she had written that day.[4] The close proximity to Lytton Strachey and Dora Carrington was also crucial to the couple’s happiness. Carrington longed for time with Julia Strachey just as Lytton Strachey yearned for Tomlin, but the couples never expressed jealousy or rivalry. In fact, Carrington expressed her delight in sharing her love for Julia with Tomlin: ‘it’s a great consolation for me to have another lovesick bird to sing duets with on the loveliness of my Julia.’[5] So intertwined was their romance, that it was on Lytton Strachey’s Ham Spray writing paper, and with Carrington's pen, that Tomlin confessed to Julia 'I seem to be in love with you, damn you.'[6]

[1] N. Strachey, Young Bloomsbury – p.75-76.

[2] L. Strachey quoted in M. Holroy, Lytton Strachey: A Critical Biography. Vol. II (1968) p.569.

[3] M. Bloch and S. Fox, Bloomsbury Stud: The Life of Stephen ‘Tommy’ Tomlin. London, M.A.B., 2020, p.112.

[4] N. Strachey, Young Bloomsbury – p.168.

[5] D. Carrington, Letter to Julia Strachey, Summer 1926 quoted in A. Chisholm., (ed.) Carrington’s Letters. London: Chatto & Windus, 2017, p.306.

[6] S. Tomlin, Letter to Julia Strachey. Undated letters from Ham Spray and Heath Studio, Julia Strachey Papers, UCL Special Collections, E1.