For the posthumous reputations of some historical figures, the History plays of William Shakespeare (1564-1616) have dealt an unkind hand. King Richard III (1452-1485), for instance, could be counted among that number. For others, the Bard has given a succinct summary that few historians could hope to rival. And this is the case of Richard’s brother, George, Duke of Clarence (1449-1478). In Richard III, Act 1 Scene 4, Shakespeare’s Clarence, confined in the Tower of London, recalls a nightmare that he has had the night before in which a ghost from his past accuses him as ‘false, fleeting, perjur’d Clarence’.[1]

Even the most sympathetic of historians would be hard-pressed to disagree with this assessment.[2] The middle son of Richard, 3rd Duke of York (1411-1460), Clarence was born into a family that was at the heart of one of the most tumultuous periods in British history, the Wars of the Roses. His father, Richard, Duke of York, had been a...

For the posthumous reputations of some historical figures, the History plays of William Shakespeare (1564-1616) have dealt an unkind hand. King Richard III (1452-1485), for instance, could be counted among that number. For others, the Bard has given a succinct summary that few historians could hope to rival. And this is the case of Richard’s brother, George, Duke of Clarence (1449-1478). In Richard III, Act 1 Scene 4, Shakespeare’s Clarence, confined in the Tower of London, recalls a nightmare that he has had the night before in which a ghost from his past accuses him as ‘false, fleeting, perjur’d Clarence’.[1]

Even the most sympathetic of historians would be hard-pressed to disagree with this assessment.[2] The middle son of Richard, 3rd Duke of York (1411-1460), Clarence was born into a family that was at the heart of one of the most tumultuous periods in British history, the Wars of the Roses. His father, Richard, Duke of York, had been a pretender to the British throne and was killed in battle for his troubles. His elder brother, Edward IV (1442-1483), was more successful and succeeded in grasping the crown from the mentally unstable Henry VI (1421-1471).

Such were the times into which Clarence was born. Coursing with ambition, Clarence sought to make himself one of the most mighty peers in the land. To this end, in 1468 he approved an ordinance that would have made the household of his estate at Tutbury Castle, Staffordshire, the largest and most expensive known of any medieval nobleman.[3]

But, in order to realise these ambitions, Clarence needed money, and his brother the king’s generous grants were insufficient. For a solution, Clarence married Isabel Neville (1451-1477), the daughter and heiress of Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick (1428-1471); nicknamed “the Kingmaker”, he was one of the most powerful subjects in the land, and his fortune was considerable. But this marriage was against the intentions of the king, who had wished to use his brother as a pawn in European marital diplomacy. Undeterred, the marriage took place in France, and when Clarence and Warwick made clear why Edward had sought to prevent the marriage in the first place. They soon waged war on the king, defeating him and imprisoning him at the Battle of Edgcote. Although they released Edward and convinced him of their loyalty, Clarence and Warwick continued to scheme to make Clarence king. When they were discovered, they fled the country again but, denied entry to Calais, were forced to make port at Harfleur. The pregnant Isabel was forced to give birth at sea.

When Clarence returned to Britain, it was again at the head of an army, this time in support of the erstwhile King Henry VI. The rebellion successfully restored Henry to the throne. However, Clarence and Warwick soon realised that the development was not a beneficial one; as former rebels, their prominent status under the previous regime had been forfeited. Whilst Clarence defected to Edward’s side, Warwick did not and was killed at the Battle of Barnet. Edward soon won back his throne and had his rival Henry executed.

The years that followed were defined both by mounting tensions and by tragedy. Increasingly, Clarence felt neglected by the king in favour of his younger brother, the Duke of Gloucester, later Richard III. Then in 1477, Clarence’s wife died. The furious – and heartbroken – earl scrambled for a scapegoat and found one in the form of a servant, whom he accused of poisoning his duchess (who in reality died in childbirth) and had executed. This act of summary justice concerned Edward; concern turned to fury later that year when Clarence took the side of one of his retainers, who had been accused by the king of treason and summoned to death. For the king, this was one act of disloyalty too many. He summoned Clarence to Westminster, where he denounced him publicly and then had him imprisoned in the Tower. Following a stage-managed trial in the early months of 1478, Clarence was sentenced to death.

In Shakespeare, two assassins enter following Clarence’s nightmare and have him drowned in a butt of Malmsey wine. Previously thought to have been one of Shakespeare’s wildest exaggerations, it now seems that his account may well reflect the truth. Contemporary sources were responsible for this rumour and, given that no other report of his manner of death exists, it could be that this was the true brutal and humiliating manner of Clarence’s death. Regardless, his rebellious spirit lived on in his children. Of the two who didn’t die in childbirth, both were executed for treason.

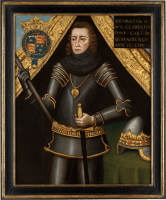

This portrait of Clarence was painted sometime between 1597 and 1603 and was originally part of a set of portraits depicting past Constables of Queensborough Castle in Kent. The set was almost certainly commissioned by the Elizabethan scholar and soldier Sir Edward Hoby (1560-1617) after he was granted the prestigious position in 1597.[4] The purpose of the portrait set was to boldly remind the viewer of the illustrious history of the office by visually representing nineteen of Hoby’s predecessors, starting with John Foxley (d.1378), who was appointed to the position in 1362 by Edward III and finishing with Hoby’s own likeness.[5]

By the time this portrait was painted, Clarence, and the majority of the other previous Constables, were long-dead, although evidence suggests Hoby made considerable efforts to research their true likenesses to ensure physiognomic accuracy. This observation is based on a recollection by an apothecary named Thomas Johnson (c.1595-1644) published in his book Iter plantarum investigationis ergo susceptum in 1629. In the book, Johnson describes how he was travelling in Kent when he happened upon a portrait of Hoby in the home of a minister from Gillingham named Skelton:[6]

I cannot omit to mention the hospitality offered to us and received (in the manner of his father) by the minister of the Church D. [doctor?] Skelton. For in his house we found a lively portrait of Sir D. Edward Hoby, most renowned in the memory of our forebears for his virtue and his study of [or enthusiasm for] good things [goods/objects?] and literature, with this inscription: I have gathered together scattered and neglected things. For with great expense and effort he collected the names, coats of arms, genealogies and, as far as he was able, the lifelike portraits of the Constables of Queenborough Castle (for thus we call the person in charge of that place), and finally he added his own. All of which have been scattered through the ill effects of time and uncultured men.

Although the identity of the artist who painted the portrait set is at present unknown, in the past they have been incorrectly attributed to Lucas Cornelisz de Kock (1495-1552), a Dutch artist working at the Tudor court. This attribution was first suggested by George Vertue (1684-1756) who found a monogram that read ‘LCP’ (for ‘Lucas Cornelisz Pinxit’) on the portrait of Thomas Arundel (1353-1414).[7] This attribution remained in place for many years and was repeated as recently as 1939 when the art historian Sigfrid Henry Steinberg published an article on the present portrait in the Burlington Magazine.[8] The broad handling of these portraits and the basic rendering of the subject’s anatomy suggests they were not painted by a top-tier artist employed at the English court and were in all likelihood painted by one of the many itinerant painters who found employment in the wealthy towns and cities surrounding London.

It is not known when the portraits were split up although we know by 1629 they were no longer at Queensborough Castle. By 1752 all sixteen portraits were at Penshurst, although six of them had been cut down to just the head.[9]

[1] In Siemon, J.R. (ed.) (2009) King Richard III: Arden Shakespeare Third Series (online edn.) [accessed 23rd October 2018].

[2] Griffiths, R.A. “Review of: False, Fleeting, Perjur'd Clarence. George, Duke of Clarence, 1449-78 by M. A. Hicks”, in The English Historical Review, Vol. 98, no. 137, April 1983, pp. 410-11.

[3] Hicks, M. (2004) “George, Duke of Clarence”, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online edn.) [accessed 23rd October 2018].

[4] For a more complete discussion of this portrait set see Daunt, C. (2015) Portrait Sets in Tudor and Jacobean England, PhD Thesis, University of Sussex, 2015, Vol. I, p.80

[5] Daunt, C. p.80.

[6] Thomas Johnson, Iter plantarum investigationis ergo susceptum a decum sociis, in agrum cantianum anno. Dom. 1629 Julii. 13 (London(?): A. Mathewes, 1629), [not paginated, A4r(?)]. Quoted in Daunt, C. (2015) Portrait Sets in Tudor and Jacobean England, PhD Thesis, University of Sussex, Vol. I, p.80.

[7] Vertue, Vertue Note Books, II, The Walpole Society, Vol. XX (1931-32) [hereafter ‘Vertue II’], p. 51

[8] Steinberg, S.H. (1939) ‘A Portrait of George, Duke of Clarence’, Burlington Magazine, Vol. LXXIV, pp.35-37

[9] Wright, J. (ed.) (1840)The Letters of Horace Walpole, 6 vols. London: Bentley. Vol. 2, p. 443. In Daunt, C. (2015) Portrait Sets in Tudor and Jacobean England, PhD Thesis, University of Sussex, Vol. I, p.84.