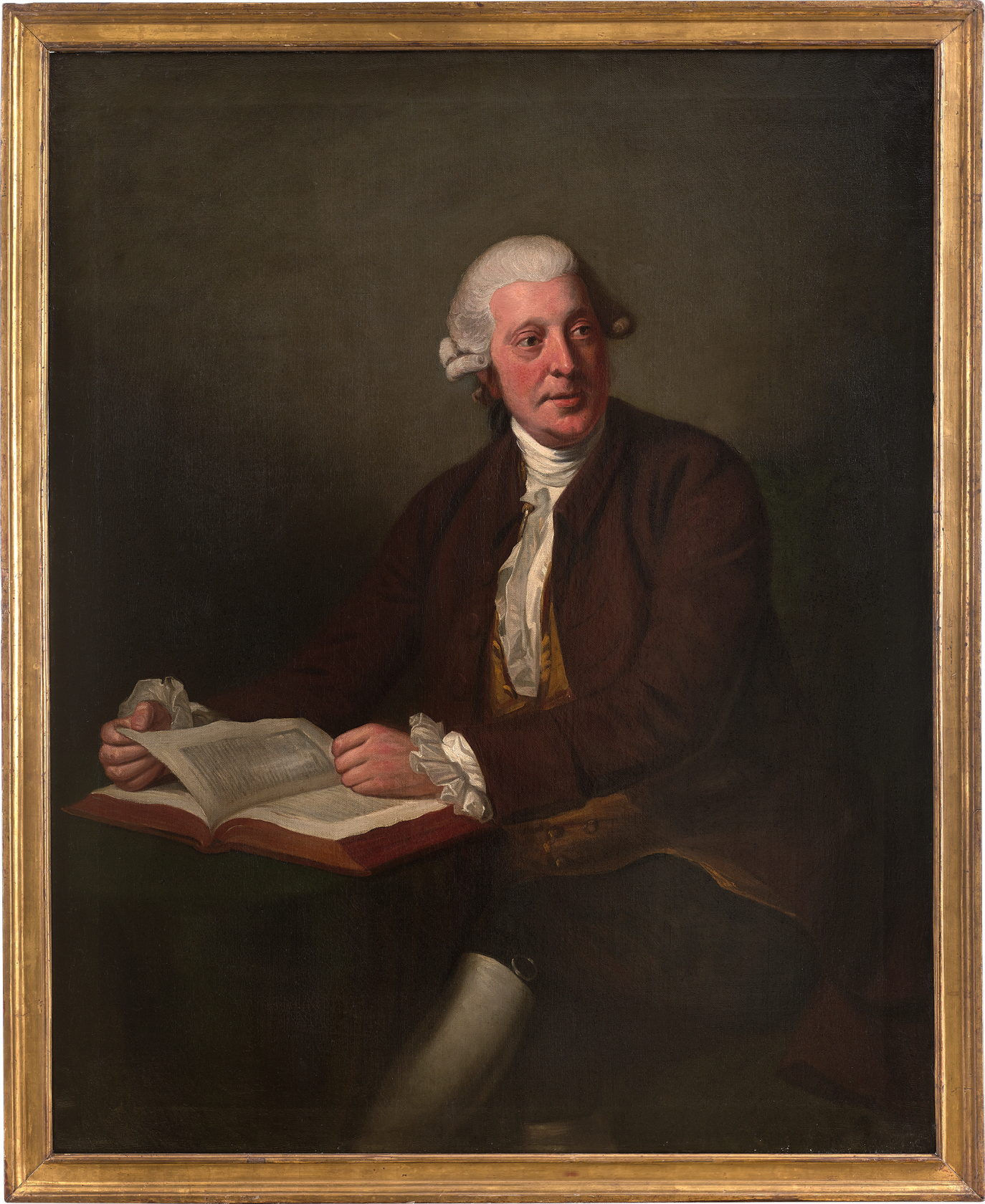

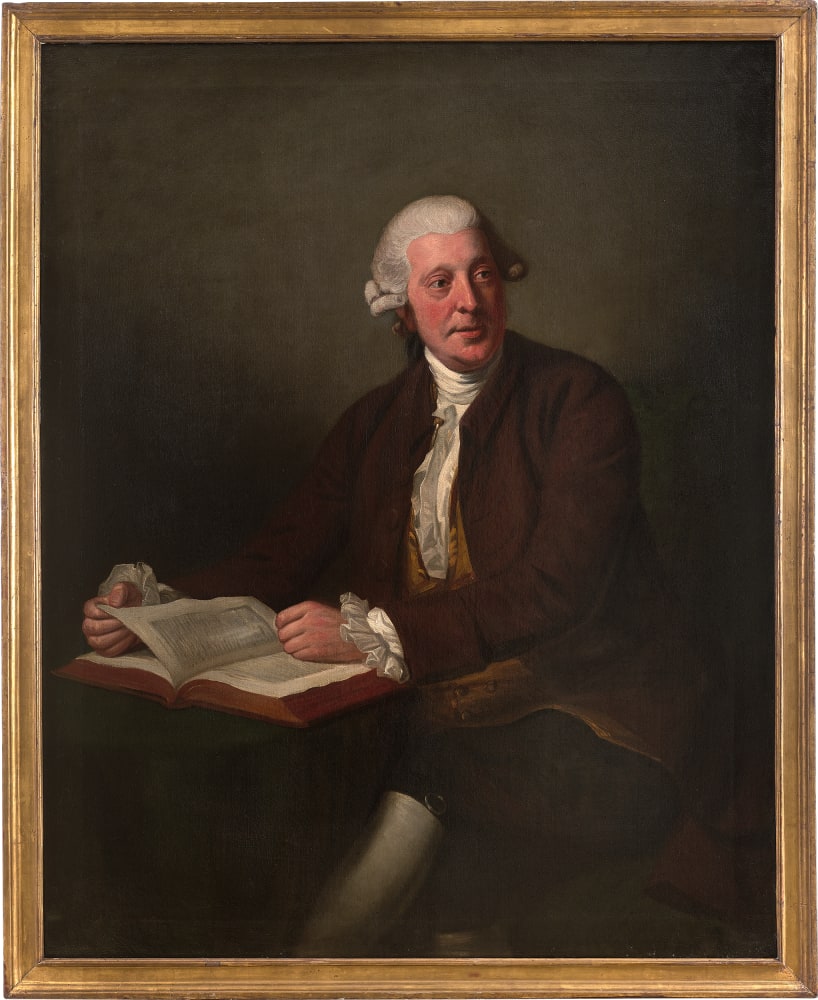

Most likely painted in 1777, this portrait shows Arthur Murphy at the height of his career. Painted by Nathaniel Dance, it represents a meeting between two of the great artistic figures of the age.

Arthur Murphy was a man of many talents. A lawyer, journalist, politician, philologist, playwright, and actor, he was the product of an age at which it was still possible to pursue a wide range of professions and still be seen to have a mastery of them all. Born in Ireland, Murphy was educated in France at the English College at St. Omer. A Catholic at a time at which this could still have severe political ramifications, Murphy registered at the college – which provided the Catholic education that it was unable to receive in Britain – under a false identity.

After a brief period as a clerk at a London bank, Murphy began to write for two of the many competing London weeklies, the...

Most likely painted in 1777, this portrait shows Arthur Murphy at the height of his career. Painted by Nathaniel Dance, it represents a meeting between two of the great artistic figures of the age.

Arthur Murphy was a man of many talents. A lawyer, journalist, politician, philologist, playwright, and actor, he was the product of an age at which it was still possible to pursue a wide range of professions and still be seen to have a mastery of them all. Born in Ireland, Murphy was educated in France at the English College at St. Omer. A Catholic at a time at which this could still have severe political ramifications, Murphy registered at the college – which provided the Catholic education that it was unable to receive in Britain – under a false identity.

After a brief period as a clerk at a London bank, Murphy began to write for two of the many competing London weeklies, the Covent-Garden Journal and the Gray’s Inn Journal (at a period in which journalistic debate could quickly turn to rancorous feud, this required some clout). 1754 was to prove Murphy’s annus mirabilis. It was in this year that he met the great lexicographer and society figure, Samuel Johnson, who was to become a firm friend and a biography of whom Murphy was later to author. Crippled, moreover, by debts, Murphy decided to make a virtue of necessity and try his hand at the London acting scene in the hope that he might make his money back quickly. His warmly-received debut as Othello later in 1754 was to be the first of many theatrical successes. Such was his success at treading the boards that Murphy soon decided to turn his hand to playwriting. In 1756, his first farce The Apprentice premiered at Drury Lane and was followed by a string of theatrical successes that meant that by the end of the season, he had earned enough money to clear his debts with £100 to spare (somewhat ironically, he was later to serve as the commissioner for bankrupts on two occasions).

Never one to limit his attention to one pursuit, Murphy had in this period both launched an anonymous weekly political journal and been admitted to Lincoln’s Inn. As a lawyer – he was called to the bar in 1762 – Murphy was successful and had a range of clients that included the great political theorist, Edmund Burke. Following the 1786 publication of all seven volumes of his collected works, Murphy continued to diversify his output, becoming a biographer of Dr. Samuel Johnson to rival Boswell and even authoring a translation of Tacitus. After an illness in the 1790s, Murphy’s productivity declined markedly; lacking a sufficient income, his debts began again to mount and he was forced to sell off books from his library before his death in 1805.

Dance was born into a talented family. His father, George, had been the architect to the City of London, and his brother, also George, was among the most successful and influential London architects of his day. Following a brief spell under the tutelage of the pre-eminent painter of conversation pieces, Francis Hayman – where he likely met the young Gainsborough – Nathaniel moved to Rome for almost nine years. Here, he worked with the great portraitist of the Grand Tourists – they shared a business card – Pompeo Batoni, learning to combine Hayman’s rococo with the grandeur of Batoni’s swagger portraits. In Rome, Dance associated with the most fashionable artistic figures of his day, embarking on an affair, for instance, with Angelica Kaufmann, with whom he was hopelessly in love and who refused to marry him on several occasions. Returning to London, he quickly established a bustling trade in portraits, painting figures as prestigious as the Duke of York. He continued to move in the most illustrious of artistic circles, becoming a founding member of the Royal Academy of Arts. In 1782, however, Dance decided to retire from portraiture to settle down and marry. Continuing to exhibit at the Royal Academy for the next decade, Dance enjoyed a happy retirement as a caricaturist.

Another version of this portrait, considered the prime, is in the collection at the National Portrait Gallery, London[1] and is distinguishable by the square, not oval buckle as seen in our work. Another version, supposedly dated 1791, was recorded as being in the collection of a W.M. Withers in 1911 and allegedly came from the collection of Alleyne Fitzherbert, 1st Baron St Helens.[2]

[1] NPG 10.

[2] Ingamells, J. (2004). National Portrait Gallery: Mid-Georgian Portraits 1760-1790. London: National Portrait Gallery, p. 356.