Full Biography

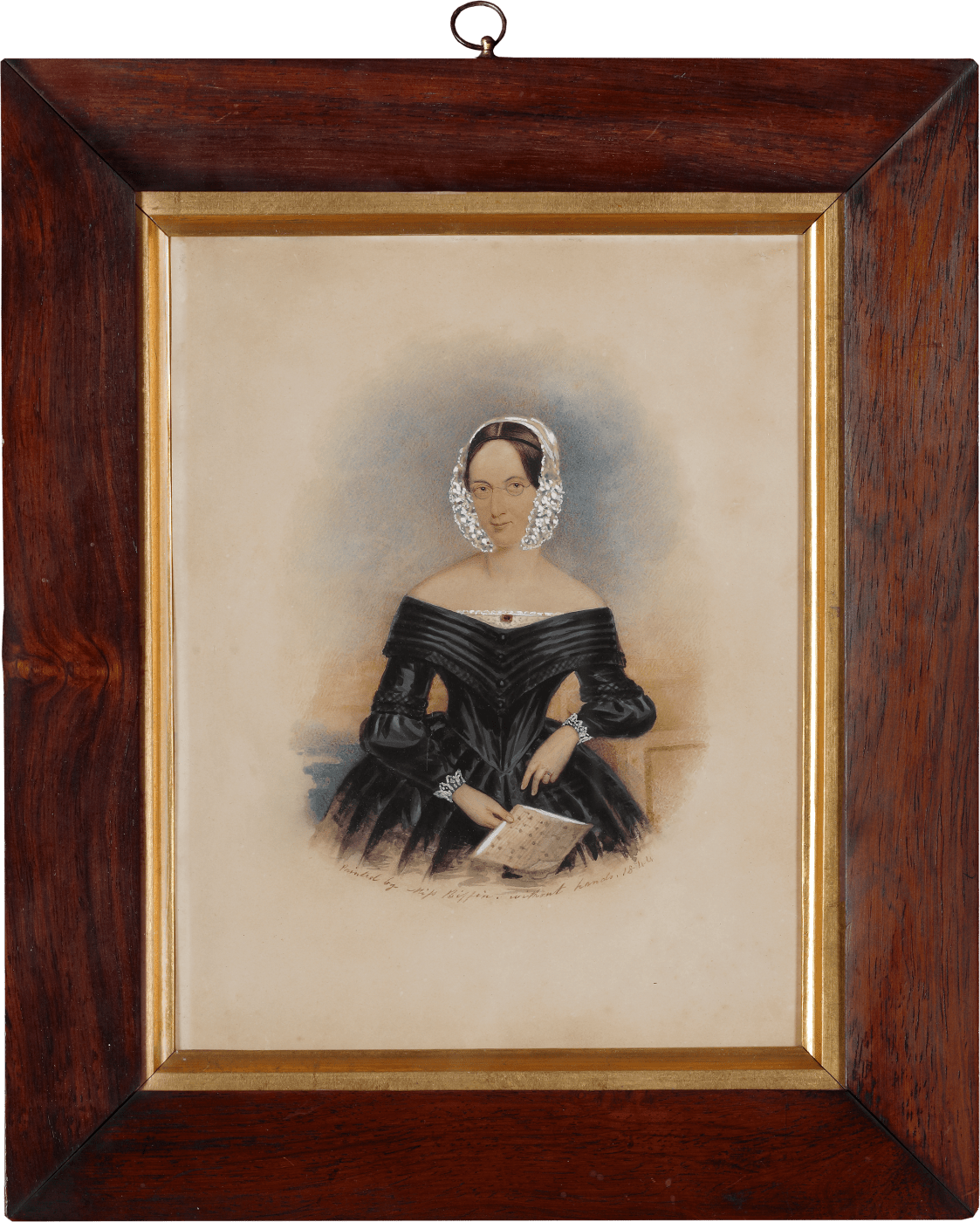

‘At the age of eight years I was very desirous of acquiring the use of my needle ... I was continually practicing every invention, till at length I could, with my mouth, thread a needle and cut out and make my own dresses.’

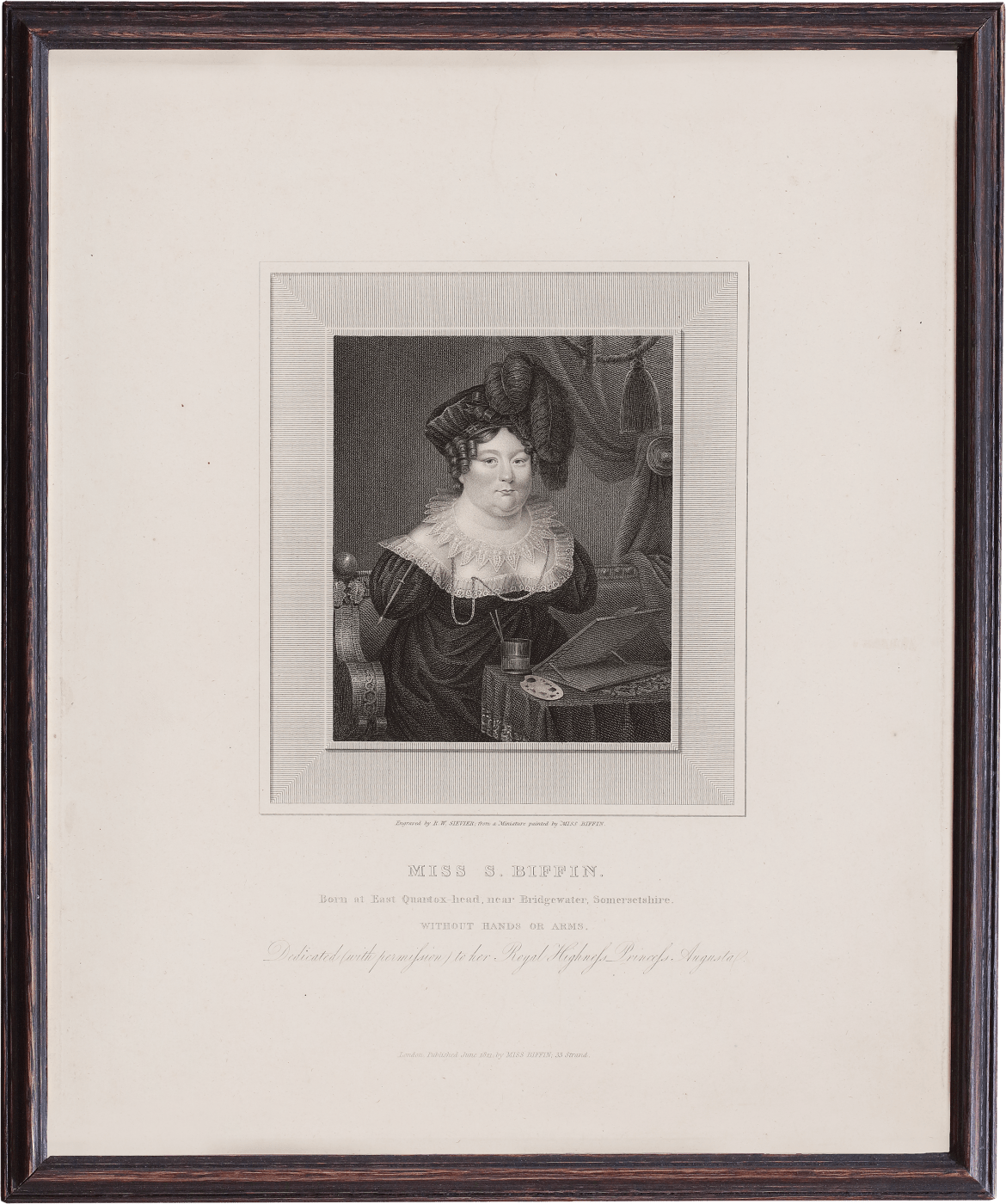

Sarah Biffin (Beffin) was born to a farming family in East Quantoxhead, Somerset in 1784. At six days old, she was baptised with her mother’s Christian name in her local parish at The Blessed Virgin Mary's Church. Her baptism record plainly states: ‘Daughter of Henry and Sarah Biffin was baptised on the 31st October born without arms or legs’. From an early age, Biffin adeptly acquired and meticulously honed skills which would aid her eventual rise to exceptional artistic fame. Instinctively talented, Biffin determined her career by diligently perfecting her artistic practice and combining it with astute commercial enterprise. Her engaging and charming demeanour positioned her as a natural networker and, within her lifetime, Biffin was celebrated internationally.

Sarah Biffin was born in 1784 to Henry and Sarah Biffin (née Perkins), a farming family in East Quantoxhead, Somerset, England. At six days old she was baptised with her mother’s Christian name and her baptism record plainly states: ‘Daughter of Henry and Sarah Biffin was baptised on the 31st October, born without arms or legs.’[1]

From the age of eight, Biffin learnt to thread a needled and sew using her mouth and shoulder, and at twelve years old she had taught herself to write. Aspiring to further artistic acquirements, in 1804, Biffin met a man named Mr Dukes who reportedly taught her the first rudiments of painting.

‘… it was suggested to my Parents that a comfortable living might be obtained by Public Exhibition, and an engagement was arranged for that purpose …’ [2]

At twenty years old, Biffin left her family home to travel across the country with Dukes. She signed a contract with her new employer and began exhibiting at fairs in regional towns and cities. Biffin would sew, write and paint in front of audiences, who were charged an admission fee and left with a sample of her writing. Pursuing a tirelessly itinerant lifestyle, she travelled to every corner of Great Britain, publicly advertising her arrival in every town and city she visited.

In 1808, she met George Douglas, 16th Earl of Morton. Morton greatly admired Biffin’s artistic skill and presented her work before King George III. He began to assist Biffin in shaping her career as a portrait miniaturist, paid for her artistic training, and she soon began taking portrait commissions across the country.

‘…I have turned my thoughts to the pursuit of miniature painting in London…’[3]

In 1821, Biffin acquired a studio in London and submitted work to the annual exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts. In May of 1821, she received a silver medal from The Royal Society of Arts. The award was announced by Prince Augustus Frederick, the Duke of Sussex who proclaimed that her work deserved the greatest honour and urged all attendees to patronise her.[4] Later that year she travelled abroad to Brussels where she became miniature painter to Willem Frederik, Prince of Orange and future king of the Netherlands.

Following the extraordinary success of 1821, little can be deduced of Biffin’s life until 6 September 1824 when she married William Stephen Wright. Although she took his name, and began exhibiting as ‘Mrs Wright’, the couple never lived together, and rumours were spread that he appropriated her life savings before leaving her.

Ever determined and entrepreneurial, Biffin continued with her professional practise and pursued teaching in lithography and painting on ivory.[5] She lived and taught in Birmingham where she shared a residence with an assistant, Miss Mary Ann Saunders, and fellow artist Mr R. Hill.[6] In 1830 Biffin moved to the fashionable tourist city of Brighton. In February 1830 King George IV bought a self-portrait from Biffin for twenty-five guineas, the highest sum Biffin had yet received for her work. [7] Biffin continued to strengthen her association with the Royal Family and in late 1830, she became miniature painter to Princess Augusta Sophia (the second daughter of King George III). Flaunting her new patronage - ‘Miniature Painter to H. R. H. Princess Augusta’ - atop her advertisements, Biffin continued garner portrait commissions.

However, Biffin’s artistic ambitions continued to press upon her. In 1841, she wrote to an unknown correspondent, asking for advice on travelling to America.[8] That same year, ‘Mrs Wright’ re-established her maiden name – Biffin – and arrived in Liverpool, which was the primary port for embarkation to America. She established a studio on Bold Street in which she hung her works and opened to members of the public who were willing to pay an entrance fee. However, Biffin never set sail for America and she remained in Liverpool until her death at the age of sixty-five in 1850.

Biffin’s move to Liverpool coincided not only with an onset of ill health, but the decline in popularity of the portrait miniature. Fortunately, she was befriended by members of the Rathbone family, well-known Liverpool philanthropists, and by Joseph Mayer, an established arts and antiquities collector. On account of her failing eyesight and dwindling commissions, an attempt to raise money for her through a subscription was organised by Richard Rathbone, a commission merchant and committed slavery abolitionist.[9]

Despite Biffin’s declining eyesight and increasingly anxious mentality, she produced numerous works during this period and procured one final crowning moment of artistic triumph in 1850. A portrait of hers was exhibited at the Royal Academy, this time under the name ‘Miss Sarah Biffin’. [10] However, a lifetime of dedication and assiduousness eventually took its toll on Biffin, and she died on 2nd October 1850. Her death certificate states she died of a ‘disordered stomach and breaking up of the constitution’.[11] Her tombstone, erected by the Rathbone family above her grave in St James Cemetery, Liverpool, read:

Gifted with singular talents as an Artist,

thousands have been gratified with the able

productions of her pencil, while her versatile

Conversation and agreeable manners

Elicited the admiration of all.[12]

________________________________________________________________________

[1] Somerset, England, Church of England Baptisms, Marriages, and Burials, 1531-1812, Somerset Heritage Service; Taunton, Somerset, England; Somerset Parish Records, 1538-1914, D\P\qua.e/2/1/3.

[2] Sarah Biffin, ‘An Interesting Narrative and proposals for a print of Miss Beffin to be dedicated, by permission to HRH the Princess Augusta’, p.1, 942 BIF/10, Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool.

[3] Ibid, p.2.

[4] His Royal Highness the Duke of Sussex (President of the Society of Arts), 1821, extract from his speech in the presentation of the Large Silver Medal to Sarah Biffin 1821.

[5] ‘Just Returned from the Continent’, Birmingham Chronicle, 10 November 1825, p.1; ‘Mrs Wright, Miniature Painter, Born Without Arms.’, Birmingham Chronicle, 17 November 1825, p.1.

[6] ‘R. Hill’, Birmingham Journal, 13 January 1827, p.1.

[7] Mr Parker (on behalf of Mrs Wright), letter to Sir William Knighton, 20 February 1830. George IV bills, GEO/MAIN/26577-26593, Royal Collections Trust.

[8] Sarah Biffin, letter to anonymous recipient, 1 September 1841. Harvard College Library; a copy of this letter is held in 942 BIF/10, Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool.

[9] The 1847 appeal consisted of an overview of Biffin’s multitude of achievements, relationships and a request to raise a total of one-thousand pounds to guarantee Biffin an income of one-hundred pounds a year. A subscription list was also circulated, headed by the Queen Dowager, followed by The Duchess of Kent, The Duchess of Gloucester and the Duke of Cambridge: Richard Rathbone, ‘ ‘Miss Biffin, Contributions to the Fund for the purchase of an ANNUITY for MISS SARAH BIFFIN’, 942 BIF/10, Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool.

[10] The exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts. MDCCCL. (1850). The eighty-second., 1850, no.695. ‘A Portrait’; Sarah Biffin, letter to the Royal Academy of Arts, London, 157877, Dept. of Literary and Historical Manuscripts, the Morgan Museum, New York.

[11] The exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts. MDCCCL. (1850). The eighty-second., 1850, no.695. ‘A Portrait’; Sarah Biffin, letter to the Royal Academy of Arts, London, 157877, Dept. of Literary and Historical Manuscripts, the Morgan Museum, New York.

[12] Biffin’s tombstone is no longer erect. Records of its inscription have been distributed in various reproductions, including the following: William Andrews, Curious epitaphs.: Collected from the graveyards of Great Britain and Ireland, with biographical, genealogical and historical notes (London: Hamilton Adams and Company, 1883), p.124-125; ‘Notes & Queries’, Somerset Herald, 16 August 1919; ‘Sarah Biffin’s Epitaph’, Daily Post & Mercury, 20 February 1925.